If there is any hope for the world at all, it does not live in climate-change conference rooms or in cities with tall buildings. It lives low down on the ground, with its arms around the people who go to battle every day to protect their forests, their mountains and their rivers because they know that the forests, the mountains and the rivers protect them. — Arundhati Roy, The Trickledown Revolution

[This is an excerpt from my 2016 book, About Canada: The Environment]

In the opening scenes of Franny Armstrong’s 2009 film The Age of Stupid: Why We Didn’t Save Ourselves When We Had the Chance, everything lies in ruin—abandoned rides sit idle in a flooded amusement park, forests are ablaze, and amid the smoldering detritus of climate chaos the planet appears to have also been severely depopulated. It’s the year 2055 and the film’s narrator, played by Pete Postlethwaite, sits eight hundred kilometres north of Norway in a global archive, a vast storage structure rising up from the no longer frozen Arctic, containing artwork from every national museum in the world, preserved animals, and electronic copies of every book, film, and scientific report ever created. Using a montage of actual news clips and interviews with real people from the first decade of the 21st century, he poses the following question to the viewer, “We could have saved ourselves but we didn’t. It’s amazing. What state of mind were we in to face extinction and simply shrug it off ?”

To answer the question, he introduces us to a number of people, one of them a 32-year-old Indian entrepreneur who in 2005 started up India’s third largest low-cost airline. His dream? To get the fifteen million Indians who take the trains every day into the sky! Most of his twelve hundred employees have never set foot on a plane. His ambition is juxtaposed against other stories making the news in India that year, like increased temperatures, flooding, and droughts, all at record-breaking amounts. The narrator also introduces us to a man in New Orleans who is credited with saving the lives of hundreds of his neighbours and their pets in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina by plucking them from their flooded homes with his boat. It was the worst weather event in the history of the city and its intensity is attributed to the warming surface temperature of the ocean as a result of climate change. He lost his own home in the rising waters and shortly thereafter retired from his “day job” as a geologist at Shell Oil, where he was responsible for analyzing samples of the ocean floor in search of potential oil deposits.

These and other examples highlight the moral dilemmas people face in their daily lives, the rationalizations and, in some cases, glaring contradictions. While the film does well to address the culpability of the individual, particularly the choices that people make on a daily basis amid the real pressures of daily existence, it also acknowledges that the magnitude of the problems we currently face—of climate change but also of habitat loss, species extinction, and environmental degradation which are bumping up against more dire thresholds—requires an effort so massive and unprecedented that it must be a collective one, “a total re-ordering of Western society,” as one individual in the film put it.

The fact is, the path we’ve been on has brought us to a daunting impasse. To continue would be suicidal, but turning it around requires courage, wisdom, and perhaps most challenging, a collective will. If one were to write an environmental history of Canada, it would basically amount to a chronicling of the resource extraction that has taken place here—furs, fish, wood, minerals, oil and gas—by those who subdued and exploited both the people and the land for commercial gain, all the while steeped in a sense of superiority and a disregard for both. Environmental historian Carolyn Merchant writes:

We live our lives as characters in the grand narrative into which we have been socialized as children and conform as adults. That narrative is the story told to itself by the dominant society of which we are a part. We internalize the narrative as ideology. Ideology is a story told by people in power. Once we identify ideology as a story—powerful and compelling, but still only a story—we realize that by rewriting the story we can challenge the structures of power.

Canada needs a new narrative, and as we shall see, a new story is being created in Canada, informed by its first peoples and the values and worldviews their societies held and continue to hold as a model to help point the way forward. And it’s happening on several fronts, as resistance movements on the front lines, in our legal system, and as part of an evolution towards a new economy.

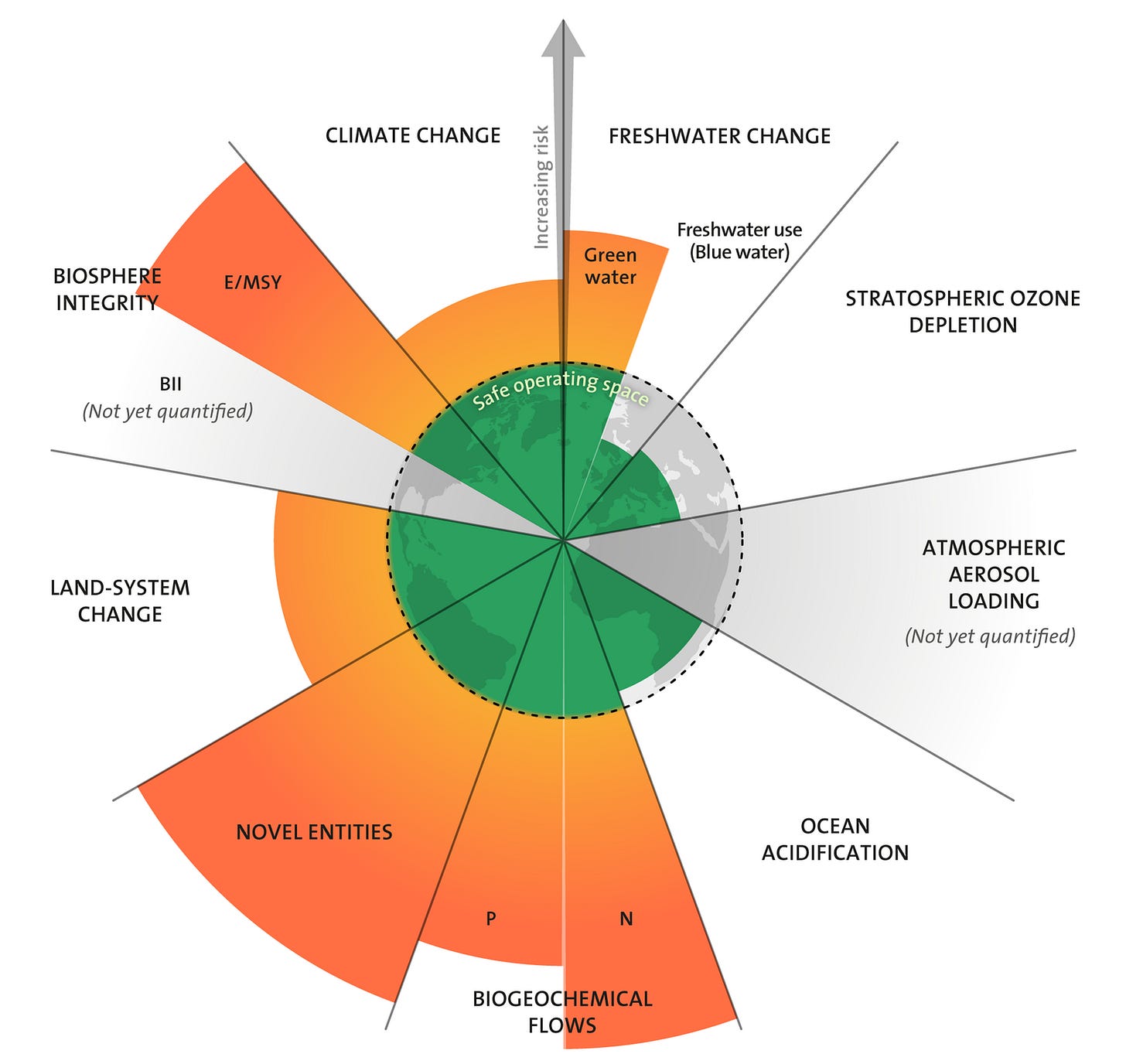

The Nine Planetary Boundaries, 2022. We are exceeding the “safe operating space” in a number of them, including climate change, but biosphere integrity, novel entities (chemical and plastic pollution), and biogeochemical flows are beyond the zone of uncertainty and are “high risk” to threaten the Earth system processes. According to the 2022 study in the journal Environmental Science and Technology, “the anthropogenic introduction of novel entities to the environment is of concern at the global level when these entities exhibit persistence, mobility across scales with consequent widespread distribution and accumulation in organisms and the environment, and potential negative impacts on vital Earth System processes or subsystems.” The authors recommended “taking urgent action to reduce the harm associated with exceeding the boundary by reducing the production and releases of novel entities.”

When Trees Have Standing

For the past 150 years Canada’s legal system has not only failed to protect the environment, but has undermined our ecological systems. Some legal historians argue that today’s laws are a product of economic forces and that the legal system actually facilitated the rise of industrial capitalism in the 19th century by providing certainty and security to elite interests.

Thomas Linzey and Mari Margil head up the Community Environmental Legal Defence Fund based in Pennsylvania. Margil says that the U.S. has a long history of overriding environmental and public health protections in favour of expanding corporate rights, and extractive and commercial activities. According to Linzey, English common law is at the root of Canada’s legal system, much like that of the U.S., Australia, and Nepal. He argues that the early colonies were corporations controlled by English common law, which explains why they all have similar legal systems today.

The founding fathers didn’t understand deforestation, didn’t understand acidification of the oceans, and wouldn’t have understood climate change. They saw an endless bounty of natural resources on the horizon and they saw their job as helping to exploit that natural bounty because that’s how you became a major power, so you didn’t have to worry about getting invaded anymore.

Linzey says the laws that evolved today are structured to “insulate” proposed development projects (extractive or otherwise) from community control. In other words, communities really don’t have a say over their futures. “People are under the illusion that we can actually govern over our communities and that we actually live in a democracy.” In reality, the permitting process—the acquisition of a permit for a proposed project—within the environmental regulatory system is undemocratic because the laws have often been developed by the industry itself. In order for it to protect the environment the legal system requires structural changes. “They didn’t set out to create a slave protection agency,” he says. They just had to abolish slavery.

David Boyd is an environmental lawyer, adjunct professor in resource and environmental management at Simon Fraser University, and author of the 2012 book The Right to a Healthy Environment: Revitalizing Canada’s Constitution. He says that here in Canada the law on corporate rights is “not nearly as awful” as south of the border. For instance, corporations in Canada do have some Charter rights such as the freedom of expression, but they don’t have the right to life, as they do in the U.S.

In Canada, courts have also given governments much more leeway in terms of passing laws that infringe on corporate rights, as long as there is a compelling justification. Corporations routinely trample on Canadian communities, but these ugly situations are not often framed in the language of rights. Corporations get permits to do awful things that harm human and environmental health, and local governments and communities don’t have the jurisdiction or the power to stop them. Mostly it is a question of political and economic clout, not rights.

When asked about the permitting process itself, Boyd points out that it’s “flawed” in multiple ways because it assumes the paramountcy of property rights, and it does not recognize any inherent rights for nature itself, instead embodying the dominant worldview that humans have dominion over the earth and that minimizing damage is the best we can do.

Port Williams dike walk, Nova Scotia. Photo: Linda Pannozzo

More than forty years ago, law professor Christopher Stone advanced the view that natural objects and areas should have legal rights. “Should Trees Have Standing? Toward Legal Rights for Natural Objects,” became arguably one of the most provocative pieces on environmental law ever written. Stone observed that throughout history rights have been conferred to those previously seen as “unthinkable,” either incapable or unworthy—children, women, slaves, endangered species, etc. and so why not nature?

Stone writes:

To be able to get away from the view that Nature is a collection of useful senseless objects is deeply involved in the development of our abilities to love—or, if that is putting it too strongly, to be able to reach a heightened awareness of our own and others’ capacities in their mutual interplay. To do so, we have to give up some psychic investment in our sense of separateness and specialness in the universe.

As we have seen, this notion of connection and love was deeply rooted in indigenous cultures. Kimmerer explains how this was evident in indigenous languages where the same words were used to address both the living world and family members—the word “it” would “never be used to refer to a person, and similarly would not be used to describe a bay, a forest, an animal, or a plant,” she says. Using the word “it” separates and objectifies living beings, a precursor to being able to turn them into “natural resources” and destroy them.

Cormac Cullinan is a practicing environmental lawyer and former anti-apartheid activist in South Africa. In his book, Wild Law: A Manifesto for Earth Justice, he writes “law is the self-directed becoming of society ... [and] legal relations embody relations of social power.” Growing up during apartheid he saw how fast and how completely social change can occur when the circumstances are right. Cullinan firmly believes that human beings will soon realize that the failure of our laws to recognize the right of a river to flow and to prohibit acts that destabilize earth’s climate, for instance, is as reprehensible as allowing people to be bought and sold.

According to Cullinan, the legal system has failed us. Decades of treaties, laws, and policies have not been able to slow down, let alone halt or reverse, the destruction of the planet. He argues that our understanding of the nature and purpose of law and governance needs to change and the only “living models of truly sustainable human governance available to us” are indigenous communities. “Seeking a new form of governance requires us to become aware of, to question, and ultimately to discard, much of what our societies assume to be true.” Cullinan pushes us “to think in a way that not only transcends our socially constructed compartmentalization of knowledge, but also to a large extent, our cultures themselves.”

Since the 1970s the environmental movement in Canada has been calling for an “environmental bill of rights,” one that attempts to protect the environment by granting humans the right to a healthy one. “Such legislation would grant increased powers to sue in civil court for damages caused by pollution and to initiate private prosecutions of pollution offences in cases where government had refused to act.” But while such a law has never been enacted in Canada, efforts are still underway to acknowledge this right. Indeed, lawyer David Boyd is a proponent of the constitutional recognition of a right to a healthy environment. In his 2012 book on the subject, he reports three-quarters of the world’s nations have constitutions recognizing this right and that overall, 177 out of 193 countries (or 92 percent) recognize our right to a healthy environment through the constitution, laws, court decisions, or international treaties and declarations. But glaringly absent from this list is Canada—something Boyd says is a “fundamental defect” of our constitution. He points to empiri- cal evidence from more than a hundred countries indicating that constitutional entrenchment results in “stronger laws, increased enforcement, an enhanced role for citizens, and improved environ- mental performance.”

But enlightened laws are clearly not enough. There are examples of countries around the world—like Bolivia and Ecuador, for instance— that have enshrined the rights of nature into their constitutions, but have done little to curtail the activities of extractivist industries. Similarly, here in Canada we’ve seen cases where enlightened laws are simply no guarantee of change. As we’ve discussed, Ontario’s 2009 renewable energy law—one that required wind and solar firms to buy and hire local—was superceded by international trade agreements. In this case, Japan and the E.U. complained to the WTO that the provisions aimed at benefitting Ontarians discriminated against foreign companies. Foreign corporations’ right to unimpeded profit can trump a country’s laws and, in this way threaten not only democracy but national sovereignty. This reality doesn’t mean we don’t fight to change laws. We have to. But it does mean we need to do more than that.

Carter’s Beach, Nova Scotia. Photo: Linda Pannozzo

Beyond Environmentalism

Pointing squarely at the need to rethink our relationship with the natural world is David Suzuki, arguably Canada’s best-known environmentalist. In 2011, upon receiving a lifetime achievement award, he told reporters that despite fifty years of working on environmental issues, things had gotten much worse. A year later he posted a commentary on his Foundation’s site, which stated,

Environmentalism has failed. Over the past 50 years, environmentalists have succeeded in raising awareness, changing logging practices, stopping mega-dams and offshore drilling, and reducing greenhouse gas emissions. But we were so focused on battling opponents and seeking public support that we failed to realize these battles reflect fundamentally different ways of seeing our place in the world. And it is our deep underlying worldview that determines the way we treat our surroundings.

Much like Cullinan, Boyd, and others, Suzuki argues we need to adopt a “biocentric view that recognizes we are part of and dependent on the web of life that keeps the planet habitable.”

Given that the dominant worldview underpinning our legal system—one that views nature as property and lacking any inherent value—is what ultimately must change to achieve real and lasting improvements, it seems that for the most part environmental groups have been barking up the wrong tree. Linzey says that the current approach taken by many of these groups is to get us to “change light bulbs and take shorter showers,” but that this will never result in us living sustainably on the earth. “Those are all good things but they’re not going to get us to the place we need to be because they validate the fact that we have no lawmaking power in our own communities to actually use the system of law to get to environmental and economic sustainability.” Linzey says civil disobedience and direct action aimed at actively interfering with unsustainable projects are the most effective tactics, and that we need to grapple with the structural issues that underpin and facilitate exploitation so that communities can actually choose the kinds of projects and the kinds of development they want.

Margil adds that the actions and strategies employed by environmental groups has served to “fracture” the movement. By focusing on single issues—one species, one stand of trees, one toxin—“we fracture ourselves pretty readily and we fail to see the common denominator that connects us all which is we don’t actually have the power to protect that stand of trees, and we don’t have the power to stop that toxin from being dumped into a frack well.” Laws and the economic system are structured to ensure this and we fail to see that connection. Boyd writes:

One of the bedrock elements of Indigenous law common to many Aboriginal societies is the idea of a living Earth, with a set of rights and responsibilities governing the relationships between humans and the natural world. As John Borrows has written, “The land’s sentience is a fundamental principle of Anishnabek law,” and it contributes to a “multiplicity of citizenship rights and responsibilities for Anishinabek people and the Earth.” Similarly, Mi’kmaq law is rooted in ecological relationships, extending legal personality to animals, plants, insects, and rocks, and imposing legal obligations on Mi’kmaq persons.

Given that this worldview—one that recognizes the standing of other species, that land is held in common, and that we have obligations to protect it for future generations is an indigenous one, it’s perhaps not so surprising that a lot of the resistance is as well: Idle No More, Elsipogtog, and the Aamjiwnaang law suit to name just a few.

Drone shot of 2018 clearcut by WestFor on crown land in Nova Scotia. Lake Rossignol can be seen on the top right. Photo courtesy: Jeff Purdy.

When is Enough Enough?

These days when I walk through the woods near my home my mind sometimes conjures up images of Windigo, the legendary cannibal monster that is part of the lexicon of characters that inhabit Algonquian folklore. Windigo is said to inhabit the cold northern forests of the Atlantic coast and Great Lakes Region of both the U.S. and Canada. As I turn a bend on the path, especially on foggy mornings, I imagine the emaciated giant, with bloody lips and the stench of decay and corruption, lurking hidden in the mist. Legend has it that the Windigo is insatiable—every time it eats it grows, and so it is always hungry. It can also transform its human victims into cannibals by consuming their flesh. Only those who have become overpowered by greed or overindulgence are its intended prey and should fear it.

According to Robin Wall Kimmerer, because sharing was essential to survival in common-based societies “greed made any individual a danger to the whole.” She says stories like the one about Windigo were designed to “build resistance against the insidious germ to take too much.” She describes how her ancestors were oriented in the world and how they understood the earth to be sacred. To the Potawatomi Nation—a tribe that originally occupied parts of Indiana but were forced to relocate twice, first to Kansas and then to Oklahoma—everything the earth provided was seen as a gift. They knew “how to say thank you,” she writes. The “cultures of gratitude” among indigenous people were also “cultures of reciprocity,” where all beings in the living world were “bound to every other in a reciprocal relationship,” where “duties and gifts are two sides of the same coin.”

It’s not enough to feel gratitude, she says, one must also give back. “Giving in return something of value that sustains the ones who sustain us.”

Kimmerer says that cautionary tales about the dangers of taking too much are ubiquitous in indigenous cultures. She says that all human people struggle with self-restraint. “The dictum to take only what you need leaves a lot of room for interpretation when our needs get so tangled up with our wants,” she writes.

While stories like this one about Windigo were necessary in order to reign in the rogue tendencies of individuals, what happens when the whole society goes rogue? What do we do then? Kimmerer says that today the “dishonourable harvest has become a way of life—we take what doesn’t belong to us and destroy it beyond repair ... How can we distinguish between that which is given by the earth and that which is not? When does taking become outright theft?” For Kimmerer it’s a matter of harm. When something is given we don’t need to inflict irreparable damage to get it. Truly renewable energy, for instance, is all around us—the wind blows, the sun shines, the tides come in and out, and the earth is warm. The other side to this—the reciprocity part—is that we need to restore the land where damage has been done.

Dalhousie University professor Anders Hayden echoes this need for restraint. In his book When Green Growth Is Not Enough: Climate Change, Ecological Modernization, and Sufficiency, he argues for “sufficiency,” which is the de-coupling of well-being from commodity consumption. At the macro level the sufficiency movement provides a critique of our current growth-based economic system, questioning unsustainable expansion of production and consumption in the already affluent global North, and on the personal level it questions what is truly required to live a good life. The sufficiency movement asks the question “how much is enough,” representing a “significant challenge to the current socio-economic order” and calls for “justice in an age of limits.”

Tree, Kejimkujik National Park. Photo: Linda Pannozzo

Decolonization

As we have seen, colonial power has shaped our worldview of nature here in Canada. This means that changing this worldview—or understanding of the world around us and our place in it—to actually reflect our place in the living world involves also dealing with assumptions embedded in colonialism. In a word, we have to decolonize. In an article that appeared in the Canadian Journal of Law and Society, Eva Mackey argues that “settler society” has for centuries entrenched in our laws, policies, and indeed our own personal expectations of life a sense of entitlement to the land. The professor of Indigenous and Canadian Studies at Carleton University studied local conflicts over land rights in southern Ontario and Upper New York State to try to understand the views of those who opposed indigenous land claims. She found that those opposed felt resentment, anger, and insecurity about their futures and the ownership of their properties, and that these were not “simply individual emotions that naturally occur.” She argues that colonial power itself “creates an illusion or fantasy of certainty,” and that land claims issues disrupt “long-standing settled expectations of entitlement.”

In Canada land claims have not led to decolonization or real autonomy for First Nations. In the words of Glen Coulthard, land claims in Canada have been based on assimilation “into existing power structures that promise to reproduce configurations of colonial power.” Mackey says that while so-called self-government processes are perceived as threatening, they are “designed precisely to avoid uncertainty and threats,” not only for non-natives, but to ensure a positive investment climate for economic development.

Mackey traces the assumptions of ownership and sovereignty back to the arrival of the colonists. “The defining colonial assumption (with continued legal standing today) ... [is] a belief in the natural superiority of Western civilization, which gave the Crown stronger and more legitimate sovereignty over the territory, simply through its arrival and assertion of its claim, and despite the vibrant collectives of Indigenous people living in the territory.” The key point here is that the narratives that shaped Canada are essentially fantasies, “a set of stories that are grounded in delusions of entitlement, which are based on irrational and illogical arguments that should make sense to no one, not even to those who created them and turned them into laws. This sense of superiority and sovereignty is lauded over not only over indigenous people but over the living world.

Mackey says decolonizing will require that we reimagine our place in the living world and recognize that we are not the masters at the helm but are part of and inextricably dependent on a vast life support system called earth.

At the end of Armstrong’s film, The Age of Stupid, the narrator introduces the fictional aspect of the film, showing video footage of events that took place in the years just before 2055, events that no longer seem so far-fetched in 2016 (as this book was going to print, only seven years after the film's release), including heat waves and water rationing in major Western cities, 100 million homeless in Bangladesh due to flooding, the extinction of half of all species, an end to skiing in the Alps, the complete liquidation of Indonesia’s forests for palm oil production, the fleeing of 100 million refugees from the Middle East, and the closure of borders in the European Union. The narrator concludes:

We wouldn’t be the first life form to wipe itself out. But what would be unique about us is that we did it knowingly. What does that say about us? Why didn’t we save ourselves when we had the chance? Is the answer because on some level we weren’t sure if we were worth saving?

This final question is of course is an attempt by Armstrong to mobilize the viewer who will not take “no” for an answer, who will not accept that human stupidity and greed will ultimately decide the fate of the planet. It is a call to action. Collective action.

Movements like the abolitionists and suffragettes were long term, generational. The movement we need now will recognize that we are part of nature and that we can’t destroy nature without ultimately destroying ourselves. The movement we need now can no longer point to single issues in isolation for us to rally around; instead, it will recognize the intrinsic value of the planet’s ecosystems and all its inhabitants. It must call for a radical shift in worldview, incorporating the ancient as well as the current lived and adapting wisdom of indigenous peoples, not just paying lip service to it and forcing it to fit into our language and structures. In practice, this means supporting indigenous sovereignty because they are our last line of defence. In practice, it means transcending capitalism, which is rooted in the mantra of free markets and unlimited growth. In practice, it means we need governments now more than ever to stand up for the good of the living world through strong regulations, laws, and policy. Just look around you. You will see that the movement we need now has sprung up all over the world, in small communities fighting for their futures. It will take generations to achieve these goals, and time doesn’t appear to be on our side, but trying is the only way we’ll ever get there. In the words of Kimmerer, “Becoming indigenous to a place means living as if our children’s future mattered.” Then, we all need to become indigenous to the place we call home.

WOW! what an impressive piece of journalism! And here in Ancaster (Hamilton) we are witnessing exactly what you spoke of...the Provincial government trampling all over our City Council's promise to preserve our Wetlands and Farmland from development. Protests and ralleys are being held; alternatives are suggested. But I think we all know the outcome.