“Nothing is so boundless as the sea, nothing so patient. It is not true that the sea is faithless, for it has never promised anything; without claim, without obligation, free, pure, and genuine beats the mighty heart, the last sound one in an ailing world. Many understand it scarce at all, but never two understand it in the same manner, for the sea has a distinct word for each one that sets himself face to face with it.” —Alexander Kielland, 1885

On January 10, 2022, nineteen days before his unexpected death, an article by Jeffrey Hutchings was published in the ICES Journal of Marine Science. It appeared as a “story from the front lines.” To introduce his piece, Hutchings included a few lines from the opening paragraph of Alexander Kielland’s 1885 novel Garman and Worse. That excerpt is reproduced above. The famous Norwegian book, named for a shipping business founded by two families, features an ungainly cast of characters, and has been described as a study of human nature.

Hutchings wrote:

“Keilland, one of Norway’s best-known writers of the 19th century, could certainly write a story. So can scientists. Each research paper is, in effect, a story. Of course, the stories we write are far removed from the stories we live. The former are planned enterprises (or contrived to appear so). The latter would constitute a research nightmare, inevitably involving unplanned turning (or tipping) points that come upon us unexpectedly, sometimes serendipitously, not always comfortably.”

Hutchings continued:

“Stories—written by novelists or scientists—have potential to motivate, entertain, inform, engage, enrage, enlighten. The most thought-provoking offer alternative, compelling perspectives on topics that we thought we knew well. Individual responses to stories inevitably differ because our life histories have molded different value systems—intellectual and emotional beacons that guide our interpretation of events and their significance. Kielland makes this point with respect to the sea which ‘has a distinct word’ for each individual who sets themself before it; as with the sea, a story is therefore the interpretation of all ‘but never two understand it in the same manner.’”

Jeffrey Hutchings (September 11, 1958-January 29, 2022) Photo: Facebook

At some point in the history of fisheries science, a fork emerged in the road, and Hutchings took the one less travelled. As an applied discipline, fisheries science became a way of monitoring fish stocks to maximize catch for the fishing industry; stocks were to be managed so that fish landings could be steady and predictable. The scientists who took this road, saw the natural fluctuations of fish stocks as a problem to be solved through intervention. But there were also the natural historians and ecologists, like Hutchings, who studied the lives of fish, how they find mates, how they learn the migration routes, and what happens when you don’t give them enough time to reproduce.

Hutchings also had another calling—one that had perhaps “come upon” him “unexpectedly” in his career, and just as he was embarking on it. Today he is arguably best known for his advocacy for the independent and unimpeded pursuit of fisheries science and its communication.

Hutchings’ career has been nothing short of astonishing. His accomplishments and accolades—too many to list here—include a 27-year teaching career at Dalhousie University as well as at universities in Finland, Norway, and Sweden; more than 250 peer-reviewed studies; editorial responsibilities with nearly ten peer-reviewed journals; Chair positions with numerous international and national fisheries as well as species at risk groups; a long-standing commitment to the Royal Society of Canada; and numerous invitations to appear before government bodies as an expert witness.

His new book, A Primer of Life Histories: Ecology, Evolution, and Application had just been published in the fall of 2021.

In his January 10 “story from the front lines”—one that almost reads like he was trying to capture the quintessence of his own life history—Hutchings argued that if science is supported by taxes, it should be free from political constraint. He quoted C.P. Snow, a British physicist and writer, who said more than 60 years ago, that “Scientists have a moral imperative to say what they know.”[i]

Hutchings continued:

“Providing science-based advice can be challenging. Personal in its reflections, the story that follows asks throughout: What constitutes an appropriate model for the communication of science-based advice that best serves society? What are the personal and institutional costs of having political and other vested interests supersede, or be perceived to supersede, scientific integrity?”

For the purposes of the journal piece, Hutchings began his “story” around 1992, when “scientifically tenuous hypotheses” about the groundfish collapse and recovery of Newfoundland’s Northern cod were “fuelling narratives that dampened institutional enthusiasm for research on overfishing.”

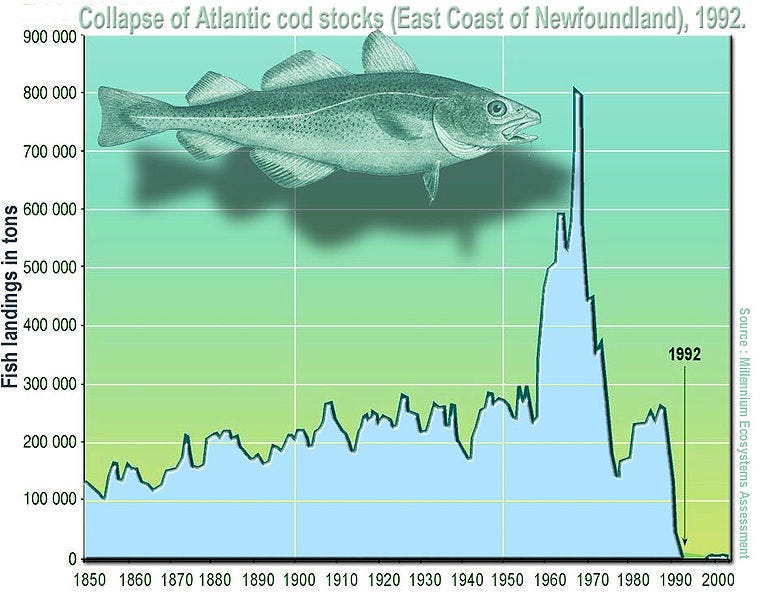

A discussion about the remarkable role Hutchings played in the aftermath of the collapse requires a setting of the stage. In 1968, 800,000 tonnes of cod from the stocks off Newfoundland were reported landed in a single year—nearly quadruple the average annual catch that had been sustained for at least the century before. One account of the sustained onslaught described the Grand Banks near Newfoundland and Labrador as being lit up at night, with “cities” of trawlers and their huge floating factories.[ii]

The killer spike of 1968, Millennium Ecosystems Assessment

What became known as the “killer spike” would prove to have profound, and some argue, permanent ecological consequences. What is most needed for a population to reproduce is large, old female fish, and the record catches of 1968 also landed all the old fish, and the accumulated reproductive potential of the northern cod stock. By 1992, a mere three decades after that gluttonous year, the cod stocks off Newfoundland had been all but wiped out—commercially extinct—with only 1% remaining.

In 2012, I had the pleasure of interviewing Hutchings for a book I was writing. At the time he described the decline in Canadian cod as “the greatest numerical loss of a vertebrate in Canada’s history.” By weight, he said, the loss of mature cod alone was equivalent to that of 27 million humans.

Of course, there was the obvious, immediate tragedy of it. The collapse of pretty much all groundfish species with any commercial value, threw 40,000 people out of work, and unravelled the fabric of rural life throughout Atlantic Canada. But there were also the long-term consequences, which were, at that point, unknown. It turns out that removing that much biomass from the ocean can shift the entire biological structure of the marine ecosystem such that scientists are still trying to understand the fallout.

When it came time to determine what had caused the collapse, Hutchings says the “scientifically tenuous hypotheses”—ones that blamed harp seals and environmental factors—were the ones that gained traction.

But in 1997—five years after the cod collapse—Hutchings tackled these tenuous hypotheses head on. At this point, two years into a tenure-track position at Dalhousie University—Hutchings co-authored a paper with Ransom Myers, which looked at whether there was any change in the mortality of cod as a result of the increase in the harp seal population. The study did not detect the effect of seals—which is what Ottawa apparently wanted it to find—so, according to its authors, it was suppressed.

Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO) messaging at the time was that seals were implicated in the collapse of the cod, but since Hutchings and his co-authors did not come to this conclusion, they were not allowed to present their paper at an international symposium on the subject—though an oral presentation was finally permitted. As well, the DFO withheld the manuscript from being published in leading journals. In a 1997 testimony to the House of Commons Standing Committee on Fisheries and Oceans, Ransom Myers said, “They censored the paper and then they denied the paper existed.”

When Myers spoke frankly to a Globe and Mail reporter saying the collapse of the cod “had nothing to do with the environment, nothing to do with the seals. It is simply overfishing,” he was officially reprimanded by senior bureaucrats at the DFO, where he worked. Shortly thereafter he joined Hutchings to pursue an academic career at Dalhousie University.

Atlantic cod, Fisheries and Oceans Canada

In 1997, on the heels of that seminal study and its suppression, Hutchings and two of his colleagues brought the issue out of the shadows and onto the international stage in a paper titled: “Is Scientific Inquiry Incompatible with Government Information Control?” The authors concluded that within the DFO, non-science influences were interfering with the dissemination of scientific information as well as the conduct of science. They said a system in which fisheries science is linked to fisheries management—as it is within DFO—resulted in the “suppression of scientific uncertainty and a failure to document comprehensively legitimate differences in scientific opinion.”

Hutchings and his colleagues called for the creation of a “politically independent” research body whose advice would have to be followed by the minister, or at a minimum, a reorganization of the link between science and management. Neither of these ideas have since been implemented.

The work of Hutchings and others had uncovered that if the fisheries research did not support government messaging, it was unlikely to see the light of day.

In Hutchings’ “story from the front lines” he notes that he paid a high price for his part in the 1997 study and coming to the conclusions he did: “[It] provoked an institutional invective in defence of the status quo, ensuring my exclusion from science-advisory initiatives related to Canadian fisheries for many years.”

Jeffrey Hutchings, Photo: National Science and Engineering Research Council

Early on in the cod collapse, hopes had been pinned on a quick recovery. At first it was thought that two years of no fishing would be enough time, but it wasn’t. In 2000, Hutchings penned a study that appeared in Nature, that found that although the effects of overfishing on a single species may generally be reversible, “the actual time required for recovery appears to be considerable.”

In 2000, Hutchings also began a 12-year tenure with the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC), where he began as a member and eventually became chair.

“I discovered how even the most politically sensitive advice on a particular topic can be effectively and independently communicated to government, unfiltered by vested interests,” he wrote in his most recent article.

In 2010, COSEWIC—with Hutchings at the helm—designated all cod in Canadian waters from the tip of Labrador south to Georges Bank as endangered. Since the collapse, most of the stocks continued to decline, something COSEWIC attributed, at least in part, to the fact that some stocks continued to be fished. Government decisions to resume fishing for cod were clearly not based in science, but on political considerations.

In 2012, again with Hutchings at the helm, the Royal Society of Canada (RSC) released a damning report on marine biodiversity in light of challenges posed by climate change, fisheries, and aquaculture. The report concluded that Canada was failing its oceans. Hutchings and a panel of ten experts recommended the discretionary power exercised by Canadian fisheries ministers— described in the report as “czar-like”—be reduced, and stated that these powers have impeded Canada’s progress in meeting obligations to sustain marine biodiversity.

The report listed the marine fish populations on the Atlantic coast that had declined by more than 80% since the 1960s and 1970s and for which overfishing had been the cause of the decline: Atlantic cod, American plaice, northern wolfish, spotted wolfish, winter skate, roundnose grenadier, porbeagle (shark), deepwater redfish, Acadian redfish, and white shark.

When I interviewed Hutchings back in 2012, the same year the seminal RSC report was published, Hutchings was clear: the federal government had shown no real commitment to developing a recovery plan for cod, and he said it was “remarkable” that after nearly two decades, there had still been no fundamental change in fishery management: no timelines, no recovery targets, no harvest control rules.

The RSC panel, headed by Hutchings, recommended that Canada enact “prescriptive legislation,” with stated objectives to prevent overfishing and rebuild depleted fish stocks. In other words, all endangered or threatened marine species should be legally listed under the Species at Risk Act (SARA), as this would automatically result in the initiation of a recovery strategy. In other words, a species could be found to be endangered, but never be officially listed.

Hutchings explained that even though COSEWIC declared Atlantic cod endangered, it was doubtful the species would ever get listed because of what are called “socio-economic” factors.

The reasons DFO gave for not listing cod was that it could “extinguish any hope” that the cod fishery might return, increasing the out-migration from rural communities. It also argued that listing cod would prohibit selling it, and since there were still cod fisheries open it would result in job losses. Listing would also affect other fisheries, in which cod is often caught as a bycatch.

During my interview with Hutchings, I sensed frustration: “DFO has sent a clear signal that any species perceived to be of economic importance would not be listed under SARA… Listing cod would mean being legally required to protect it, and this would mean having to change the way we fish.”

By 2012, Canada was also experiencing what could be called a dark age, a result of six years of governance by Stephen Harper. In addition to changing more than 70 laws, dismantling decades of environmental protection, and undermining Aboriginal and Treaty rights, the Harper government cut funds to the marine mammal contaminants program, as well as to the budget of Library and Archives Canada. A number of federal science libraries were closed and their collections culled, and federally employed scientists were “muzzled” in a campaign to control their message and the media’s access to them.

When I interviewed Hutchings, the country was in the midst of this turmoil. He seemed worried about the government’s increasing preoccupation with controlling and disseminating information. Hutchings told me that the information control he was witnessing at that time was much worse than anything he personally witnessed in the past. He said that while there was more scientific information available to the public (such as electronic documents of published reports, for instance), there was “far greater government control over the communication of scientific information by government scientists in the past five years than existed previously.”

Even after the government changed hands, the situation for government scientists did not appear to improve.

But for Hutchings, it was the silence from the public that was most deafening:

“The extremely sad element to this, in my view, is not that the government is exerting that control, but that the Canadian public, through its silence, is implicitly accepting this control over it. Even the Soviet Union had its dissidents.”

Hutchings’ book, A Primer of Life Histories: Ecology, Evolution, and Application, was released in 2021.

Melanie Massey, a PhD candidate at Dalhousie’s department of biology, was one of Hutchings’ students. Massey says Hutchings was “revered” by his students and will be remembered as an “impassioned speaker and storyteller,” with an ability to “distill complex ideas into simple terms.” Hutchings was also generous with his time and participated on a number of students’ committees, and took a personal interest in their lives.

“He was always supportive and made students feel not only comfortable, but also capable,” she says.

Massey recalls how Hutchings encouraged her and her fellow graduate students to pursue their own direction with their research, and supported their mental health and well-being by encouraging them to take time for themselves.

“He was patient and non-judgemental. He put our problems into perspective and changed the way we looked at them—something he had a real knack for, whether in the realm of science or the realm of intrapersonal relationships. My colleague described the wisdom he imparted to us as ‘poetic.’ It's no surprise he is remembered by his peers at COSEWIC as a peacemaker.”

“His humility made it easy to forget he was one of the most famous fisheries and life-history scientists in the world,” Massey noted.

At his memorial service, held in his home town of Orillia, Ontario, his siblings, and long-time friends remembered Hutchings as someone with a sense of humour, who laughed a lot, was deeply authentic, as well as being caring, kind, and humble about his accomplishments.

“He was destined to follow the beat of his own drum.”

Finally, in his “story from the front lines,” Hutchings pointed to his 9-year position as an independent scientific advisor to Loblaw Companies as one that he found to be “personally fulfilling.” In 2009, the company had announced that by 2013 they would only sell sustainably sourced seafood, a move that would require the company to get scientific advice. Within a month of its announcement, Hutchings was approached because they wanted an “honest broker” to help guide the choices. Hutchings said the position offered “the most direct, impactful, and meaningful opportunity I have had to provide science advice to decision-makers in a way that has short-and-long-term benefits to sustainability.”

Ultimately, Hutchings held this view of the role of a scientist: “Scientists are obliged to be the best advisors that we can be.”

There is no question that Hutchings took this role to heart, and fulfilled it in spades. In this way he was a beacon for his colleagues and students, for his family and friends, and for anyone who was looking for an “honest broker.” He was also a beacon for me.

The world has lost an important voice, but the reach of his influence knows no bounds.

In his “story from the front lines,” this is what Hutchings wrote about what he hoped his “story” would achieve:

“Perhaps this story will serve as a template for others to reflect on the ongoing challenges of providing science advice that is free from real and perceived vested interests, honest and objective about facts and the weight of evidence, clear about what is known and what is not known, and faithful to the peer-reviewed literature about what is relatively certain and what is highly uncertain.”

Jeffrey Hutchings was survived by his daughter, Alexandra, his parents (Wendy and Alexander), and his partner Anna Kuparinen. He also leaves behind siblings Stephen, Julia (Brian), and Jamie, and his dear friend Joyce Yates.

May he rest in peace.

[September 11, 1958 - January 29, 2022]

[i] The C.P. Snow article that appeared in the 1981 edition of the New York Times was an excerpt of a speech Snow delivered in 1960.

[ii] Rose, G. 2007. Cod: The Ecological History of the North Atlantic Fisheries. St. John’s: Breakwater Books.

This is an incredibly powerful, poignant and beautiful piece of writing about an incredible man and scientist. I am writing this with tears falling on the keyboard. I didn't even know him, just interviewed him twice last year, and was bowled over by the depth of his knowledge and expertise, his gentle and kind demeanour, and his commitment to his calling - the ocean and what lives in it (and trying to protect it all from human beings intent on destroying it). Thank you so much, Linda, to preserving his life and legacy this way.

What an amazing tribute to Dr. Hutchings.