Pushing Back the Hospital Curtain

Data obtained through Freedom of Information show that SARS-CoV-2 was directly responsible for a tiny fraction of hospital stays in Nova Scotia, so why did it threaten to overwhelm the system?

It was being called the “new normal.”

Emergency department closures in small town Nova Scotia were being announced almost daily because there weren’t enough doctors. Even the province’s Auditor General Michael Pickup admonished the province for its long wait times—one of the highest in the country—and for not adopting his 2014 recommendations to deal with operating room usage and surgical wait-time reporting. The gaps in service were not only undermining the principle of universal access but were becoming routine.

You’d be forgiven for thinking the health care system crisis being described here was the result of the pandemic. But it was not. This “new normal”—which is how it was being described at the time—predated the pandemic. News reports from 2017, 2018, 2019 were already shining a light on a system in serious crisis.

This was the inconvenient truth raised by one reporter in mid-April of 2020, not long after the World Health Organization declared the pandemic, and just as the province was renewing the state of emergency—one that would last nearly two years. At a COVID-19 press briefing Michael Tutton from the Canadian Press asked Premier Stephen McNeil the question that really was the elephant in the room:

“Premier, the unions that represent workers in nursing homes say that the COVID crisis is revealing a deep underlying problem of staff shortages that should have been remedied years ago. It will continue to reveal that… Does this cause you to reflect and think the time has come to change those staffing levels in Nova Scotia?”

By that point, 44 people had died, 38 of them were residents at Northwood, the province’s largest long-term care facility, located in Halifax, and the epicentre of the disease.

Instead of acknowledging that both health care and long-term care—two systems which are intertwined—were both chronically underfunded, McNeil got defensive. Instead of acknowledging that his government had fudged nursing home waitlists, that patients were suffering interminable wait times, that the system was unable to deliver care, and that it was putting patients and staff at risk, McNeil replied, “This is not, quite frankly, the time for anyone to begin to negotiate contracts of staffing models. This is about a time of Nova Scotians coming together to ensure that we provide the frontline workers with the support they need, and wrapping our arms around each other in this community.”

We all know that the purpose of the first lockdown was to “flatten the curve,” so our health care system wouldn’t buckle under the surge of serious cases. But by the spring of 2021—a year later—we were hearing the same refrain. Businesses deemed non-essential were forced to close, we were back to household bubbles, public and private schools closed across the province, the border got even tighter, and exemptions that had been in place for funerals and for allowing immediate family members to be with their loved ones at the end of life were removed. At the time, the province’s Chief Medical Officer of Health, Dr. Robert Strang was quoted saying, “With almost 100 people in hospital, we all have a responsibility to our fellow Nova Scotians to keep them safe and stop that number from getting higher.”[1]

Now, thanks to data obtained through a Freedom of Information Request, the COVID-19 hospitalization numbers can be seen in the context of all hospitalizations, a perspective that has been sorely missing until now.[2] The 82-page document (embedded below) shows the number of hospital admissions and ICU “visits” by “most responsible diagnosis” for a nine-month period from December 14, 2020 to September 30, 2021.

Most responsible diagnosis

Throughout the pandemic, COVID-19 hospitalizations have been used to indicate the strain being put on the health care system. Nova Scotians were informed regularly about the number of COVID patients in hospital or in the ICU. It was as if there was an invisible line: exceed this number and all hell is going to break loose; stay below it and lockdowns and strict public health measures can be avoided. But what did these hospitalization numbers actually mean? Was this laser-sharp focus reasonable, or was it myopic? How did the COVID numbers compare to the other reasons why people were in hospital?

Did putting COVID-19 hospitalizations under a microscope make us lose sight of reality?

To help me understand the data, the Nova Scotia Health Authority put me in touch with Matthew Murphy, its Chief Data Officer and Senior Director of Strategy and Performance. He also teaches in the School of Health Administration at Dalhousie University.

Matthew Murphy is Chief Data Officer for the NSHA

The first thing I asked Murphy was to explain the meaning of “most responsible diagnosis.”

“In the world of hospital stays, we employ a group of people called coders. At the end of each hospital stay, they read the full hospital record and they assign a series of codes that we then use, for all manner of things such as billing, analytics. One of those codes is called most responsible diagnosis or MRDx. It's what we think of as, why you were in the hospital. So technically, it means it is the diagnosis that accounted for 50 percent or more of the resources you consumed while you were in hospital. For instance, you can come in with a fractured femur, but while you're in hospital, you develop pneumonia or you develop sepsis and then have subsequent complications and ultimately you stay in hospital for a very long time and most of the resources are actually to treat your systemic infection and not your fractured femur. So even though you were brought into the hospital for a fracture, your most responsible diagnosis may end up being sepsis or septic shock or septicemia. So, if you're in hospital for 10 days, whatever accounted for six days is what we give as your most responsible diagnosis and that's how we plan most of our hospital system.

So, the MRDx is the one diagnosis which describes the most significant condition of a patient—the one that causes the stay in hospital. When there are multiple diagnoses, the "most responsible" one is the diagnosis causing the greatest length of stay, and it might not be the same as the reason the person was admitted in the first place.

Murphy also explains that the ICU numbers are a subset of the admissions numbers, which can be thought of as an “overarching bucket.” So, for example, in wave 4/5—which wasn’t captured in the FOI data because it only extended to September of 2021—there were 669 admissions and 83 ICU stays for COVID-19. “These are not mutually exclusive,” says Murphy. “A patient can often progress from the medicine unit to ICU and back to medicine, so the 83 is a subset of the 669” rather than in addition to it.

But here's what struck me the most about the hospitalization data. During that nine-month period, 304 hospital admissions and 80 ICU stays were for “Coronavirus disease 2019 [COVID-19] virus identified.” But during the same time period there were thousands of other hospital admissions for more than 5,700 other diagnoses.

For instance, there were:

o 3,754 admissions and 844 ICU stays for congestive heart failure

o More than 6,440 admissions and 388 ICU stays for malignant cancers (neoplasms)

o 3,380 admissions and 327 ICU stays for mental and behavioural disorders

o 5,193 admissions and 716 ICU stays for palliative care

o 4,595 admissions and nearly 950 ICU stays for Type 2 diabetes

o 322 admissions and 126 ICU stays for intentional self-poisonings (alcohol and drugs)

o 3,380 admissions and 327 ICU stays for mental and behavioural disorders due to drug use (alcohol, cannabinoids, cocaine, hallucinogens, opioids)

o There were also 2,330 admissions and 99 ICU stays for people waiting to be admitted into a long-term care facility elsewhere.

To reiterate, there were more than 5,700 “most responsible” diagnoses listed, and COVID-19 was just one of them. There were thousands of hospital admissions (including ICU stays) over the course of nine months. COVID-19 accounted for a tiny fraction of these.

To see a select list of MRDx for hospital admissions and ICU stays just click on this embedded link:

I point this out to Murphy. I ask, “When compared to all the other “most responsible” diagnoses, the COVID-19 numbers look miniscule. Given the number of hospitalizations for other illnesses, why was the overcapacity or strain on the health system being attributed to COVID-19?”

“A very good question,” he replies. “Our system ran at high capacity pre-COVID-19. We regularly would have had occupancy rates at 80% and 90% and on occasion we did tip over into overcapacity,” explains Murphy.

Murphy attributes the post-COVID overcapacity to “two main things”: One, it is a net addition. It is a new virus with a net new number of patients who previously didn't come to hospital. One of the other challenges that it presented was the impact to our workforce. So as our workforce either contracted COVID-19 or went into isolation because they've been exposed to COVID-19, it compromised our ability to staff all of our beds.”

Indeed, on April 5th it was reported that 625 employees of the Nova Scotia Health Authority were off work because of interactions with COVID-19 – either infected with the virus, a close contact with someone who was, or awaiting a test result. The NSHA also reported that hospitals across the province were running at 99.5% capacity—a subject we’ll return to.

“I think it is fair to say that COVID-19 is not necessarily the only reason we're in overcapacity. It is a contributing factor and this is a new factor, but I don't think you can discount the other, say, 2,900 patients who are in the hospital [at any one time],” he says.[3]

Murphy also points to the impact of the growing long-term care waitlist for people who are in hospital who need to be moved into long-term care. “At any point in time, you might see the same or greater number of long-term care patients. Ironically, a number of the long-term care beds are closed because the long-term care centres have staff who are off because of COVID-19, so it is an interrelated challenge. But I think it is reasonable to ask the question, ‘Is COVID the express cause of overcapacity or is it a key contributing factor among other system challenges that may have already been present?’

When it comes to reporting the COVID-19 hospitalization numbers, Murphy says providing a clear picture to the public of what was happening was a “challenge.”

Murphy explains that the designation of a “most responsible diagnosis” is one of the main reasons why his department fields so many media requests.

“Day to day, our numbers sometimes seem inconsistent, and it’s because a patient can move from one category to another.” For instance, a patient might be admitted with one diagnosis, but also happen to have COVID. On the second or third day, they might suddenly need most of the resources/ care to be focussed on the COVID-19. If the patient requires that specialized care, the hospital would switch their “most responsible diagnosis” (MRDx) classification.

“We're trying very hard to make sure we quantify or categorize people correctly, both because it impacts how we model, but also it will impact how we plan for the future to understand which group of people require which resources when,” says Murphy.

Murphy says the distinction between being admitted with COVID-19 and being admitted because of COVID-19 was made because of how it relates to the MRDx.

“We do see a very large number of people who have been hospitalized, who are positive for COVID-19 and who require specific infection prevention and control measures, so it’s important we know who they are, but their MRDx isn’t going to relate to COVID-19, it’s going to relate to something else,” he says.

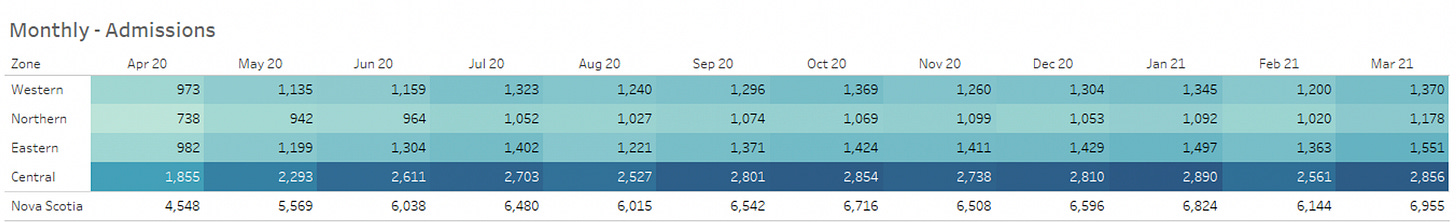

Murphy says that at the end of a fiscal year it’s also important for the NSHA to know how many patients were treated at each facility in the province. When monthly admissions are examined, we see that April 2020 saw the lowest hospital admissions of any month in the last 4 years: when only 4,548 people were admitted to hospitals in the province compared to 6,566 a year later.

Inpatient Indicators by Zone: Shows total admissions by month and zone from April 2020 up to Jan 31, 2022. Data provided by Matthew Murphy, Chief Data Officer with the NS Health Authority.

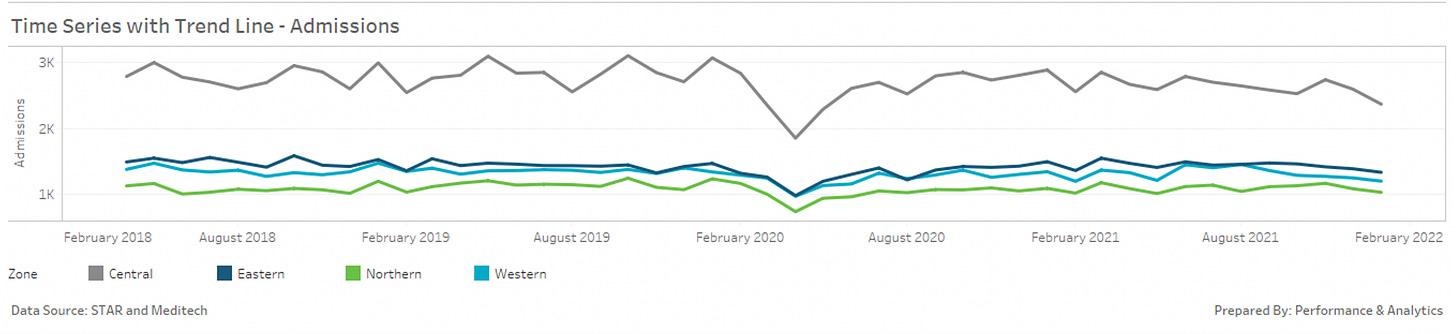

Time series with trend line showing total admissions by month and zone from February 2018 up to Jan 31, 2022. Courtesy of Matthew Murphy.

3,380 admissions and 327 ICU stays for mental and behavioural disorders due to drug use

While it isn’t something I’m able to analyze yet, I was also struck by the sheer number of people whose MRDx was for mental or behavioural disorders involving drug use. Statistics Canada data now show that during the first year of the pandemic, from the end of March 2020 to the beginning of April 2021, 73% of the excess deaths among those under the age of 65 was not a result of dying from COVID 19, but a result of drug and alcohol use, a side effect of the lockdowns and the restrictions.

While I’m sure there is much more to learn about this, given the share of deaths being attributed to this category, I can’t help but wonder how many drug and alcohol-related hospitalizations in Nova Scotia were a side effect of lockdowns and restrictions?

Engaging in this analysis would require hospitalization data by MRDx for several years prior to 2020, so that a meaningful trend line could be constructed. But there is no question that the repeated public health measures to “flatten the curve” had unintended consequences, including a population shift in the direction of poor mental health.

Tipping into overcapacity

Now, I’d like to return to something Murphy pointed to earlier: Nova Scotia’s hospital “occupancy levels” or the percentage of staffed hospital beds that are occupied on any given day. Recall that on April 6th the NSHA said that hospitals across the province were running at 99.5% capacity. Infectious disease experts and others are now calling on Premier Houston and Dr. Strang to return to restrictions and mask-wearing, as if 99.5% capacity is an unusual occurrence.

But if we look at hospital-based data showing the “daily occupancy trend” dating back to January 1, 2019, there is nothing unusual about this level of capacity.

Murphy provided me with occupancy data starting January 1, 2019 to March 29, 2022. I’ve included screen shots below of the “patient flow dashboard.” As you can see, the daily occupancy levels—by zone as well as overall—fluctuate quite a bit, and while 85% is the target occupancy level, occupancy often exceeds 100%, meaning it often tips into overcapacity. What I find most interesting (and troubling) about the data is that tipping into overcapacity was almost the norm prior to the pandemic, and that during the pandemic we saw some of the lowest occupancy rates—likely a result of people avoiding the hospitals, as well as cancellations of surgeries.

Provincial patient flow dashboards for the 4 zones (top) and for NSH overall (bottom). Take note of how capacity (> than 100%) appears to be exceeded more often prior to the pandemic. Courtesy Matthew Murphy.

Modelling hospital strain

At the federal level, much of the forecasting involving hospital capacity has been based on modelling by the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC), and one of the key modelling assumptions used to predict hospital strain is that the hospital bed capacity available for COVID-19 patients in Canada is 31 beds per 100,000 people. According to Anne Genier, a senior media spokesperson for PHAC, the statistic “31 beds per 100,000” is cited in Public Health Agency of Canada’s (PHAC) Update on COVID-19 in Canada: Epidemiology and Modelling, a public presentation from December 10, 2021. This estimate was based on internal data regarding the number of hospital beds occupied by COVID patients in Canada in January 2021.

According to Genier, the number of beds occupied as well as overall capacity “has been evolving over the course of the pandemic, and across provinces and territories,” and that currently 31 beds per 100,000 represents approximately 18% of hospital bed capacity in the country.

Here in Nova Scotia, modelling hospital capacity was a shared endeavour by NS Health, the IWK, and the Department of Health and Wellness. While the work of the PHAC was incorporated, the modelling was done a little differently here.

“We don't use beds as an input, we use hospitalizations as an output, and use that to strategize bed availability through surge planning,” says Murphy.

According to Murphy, the number of hospital beds available plays an important role in determining what system mitigations need to be put in place. Unlike the PHAC, Nova Scotia based their modelling on cases.

“So, we didn't expressly say we need to have 31 beds at all times, but instead we said, within Nova Scotia, these are the cases, and some of these cases will translate to hospitalizations, so what are the operational plans or surge plans that are in place to make sure that when we have the next one, or next 10 COVID patients, that we will have a bed available for them?... And if there aren’t the number of hospital beds available, what type of system mitigations can we put in place in terms of surgical slowdowns, ambulatory care slowdowns—responses like that to create the capacity?”

Clearly a lot seems to be riding on the number of staffed hospital beds.

In fact, it’s a key indicator of the resources available for delivering services to hospitalized patients and it says a lot about the quality of a country’s health care system.

Neoliberalism is often associated with the economic policies brought in by Margaret Thatcher in the United Kingdom and Ronald Reagan in the United States. Camp David, 1984. Wikimedia commons

Drinking the free market kool-aid

In Canada the big shift started around 1988 with the Canada-US Free Trade Agreement. Conservative Prime Minister Brian Mulroney called it a deal that would “determine the future of Canada.” Meanwhile, Liberal leader John Turner said it would “destroy a 120-year-old dream called Canada.” The deal, which was later expanded to include Mexico, set the stage for what is commonly referred to as neoliberalism, but it could just as accurately be called free market ideology, hyper-capitalism, market fundamentalism, or corporatism. Regardless of what it’s called, it embodies five main elements: markets should be free to operate with little or no government intervention, barriers and restrictions to the free exchange of goods between countries should be removed, anything that can be privatized should be, the concept of public goods and community should be replaced by private property and individual responsibility, and government spending—one that is most relevant in this context—is considered wasteful and inefficient and should be reduced (unless of course it’s being given to the private sector).

This new dogma involved a hands-off approach to economics: the unrestrained accumulation of capital, the concentration of private power and wealth and a hollowing of the protective and interventionist role of government.

As we’ve seen, four decades of neoliberal policies and austerity measures have weakened the capacity of Canada’s health care system to respond to the demands of daily living, let alone a pandemic. In other words, even though Canada has a universal health care system, it’s one that has been underfunded for years, exposing the weaknesses of this vital infrastructure.

This hollowing out of the health care system can be seen by looking at both health care funding and hospital beds.

In Nova Scotia, data from the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI) indicate that since 2000, public health care spending has stagnated in real terms. In other words, after adjusting for inflation, the dollars spent in 2019 are not that much different in terms of purchasing power than the dollars spent in 2010, even though the population has increased, and it’s an aging one. When you look at per capita spending in real terms, in 2010 the province spent $2,900 per person and by 2019, nearly a decade later, it had only increased by $100 — to just over $3,000.

The number of staffed hospital beds available is considered an indicator or measure of the health resources available for delivering services to patients. According to data from the World Health Organization, the downward trend in staffed hospital beds for Canada began somewhere around the time that neoliberalism was starting to take hold.

Canada’s downward trend in staffed hospital beds begins around the time that neoliberal economic policies were starting to gain traction. World Health Organization.

According to data for 2020 provided by the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)—an intergovernmental economic organization with 38 member countries—Japan had 13 hospital beds per 1,000 population, the highest of all countries, while Canada ranked closer to the bottom with only 2.5 beds per 1,000 population.[4]

Hospital beds per 1,000 population, 2020, OECD.

According to the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI), in 2013-2014, Nova Scotia had 410 staffed hospital beds per 100,000 population. Today the number sits closer to 360.

In April 2020, the Canadian Centre of Policy Alternatives reported there were already lessons to be learned from the pandemic about long-term residential care, which is where most of the fatalities occurred across the country. The changes include developing a universal public long-term care plan that is accessible and adequately funded; stopping privatization and promoting non-profit ownership; ensuring protective equipment is stockpiled for the future; building surge capacity into labour force planning and the physical structure of facilities; and establishing and enforcing minimum staffing levels and regulations.

These were among the weaknesses the pandemic laid bare, but it did not cause them. If anything is to change, the cause must be addressed. The question is, how did a dogma that doesn’t give a rat’s ass about the public good become the new modus operandi? And what can we do to change it?

[1] During the third wave, Nova Scotia Health was also in possession of 150 doses of potentially life-saving monoclonal antibody treatments for early treatment of high risk COVID patients, to help to keep them out of the hospital, but only one dose was used. I have written extensively on this subject and you can find my articles about it here, here, and here. You can also find a deep dive on the subject on my blog, here.

[2] This information was obtained through Freedom of Information by a member of the public and was sent to me.

[3] Murphy’s numbers refer to the number of hospital beds in the province occupied by non-COVID patients. The statement was meant to be illustrative, rather than accurate, as there are roughly 3,600 staffed hospital beds in the province (including the IWK) and there have never been 700 COVID patients admitted at any one time.

[4] According to the OECD, it has 38 member countries, however, the chart, indicating hospital beds per 1,000 inhabitants, lists 41 countries, including China, Russia, and India. Total number of hospital beds includes both acute care beds and psychiatric beds. When only acute care beds are considered, Canada comes fourth last (only Chile, Sweden and Colombia ranked lower). Canada had just 2 acute care beds for every 1,000 residents. The top-ranked country, Japan, had 8 beds per 1,000.

Excellent work Linda! We are so lucky to have at least one journalist here not afraid to ask important questions and honestly seek the truth. Unfortunately the fourth estate is now owned, controlled and used by the destructive forces of neoliberalism. Hopefully other journalists and editors will be inspired and emboldened by your work!

Excellent and fascinating article Linda. Covid 19 has been a very convenient scapegoat for the depredations of neoliberalism and government/corporate malfeasance, and like every crisis, has been exploited to accelerate the process, further shift resources and power upwards, and further attenuate our fragile democracies. The gutting of regulatory agencies has been a critical element of this process so that the institutions most involved in pandemic response, like the pharmaceutical industry, is a major funder of these agencies and is virtually self-regulating. What that means for the safety and efficacy of its vaccines is just starting to trickle out now thanks to a federal judge in the US ordering the release of Pfizer’s suppressed trial data, and the picture is not pretty. The systematic suppression of effective, potentially life-saving treatments is another part of this sordid story with a death toll that will never be calculated. Meanwhile private ownership and perfunctory monitoring of already sub-human standards of care at LTC facilities transformed many of these institutions into pandemic torture chambers where society’s most vulnerable were subjected to unspeakable suffering and indignity at the end of their lives. And how many of the metal health hospital admissions and diseases of addiction are a result of people trying to cope with the psychological stresses of poverty and isolation which are predictable results of neoliberal policies, stresses massively exacerbated by pandemic restrictions. In all these instances a biological virus is being used to hide the epic injustice and criminality of an ideological/economic virus that is overwhelming the immune system of our democracies and destroying the planet’s own life systems. Unless we develop resistance to *that* disease, which you have accurately identified and of which our over-capacity hospitals are one symptom of many, it will make Covid 19 look like a walk in the park.