The Atlantic Whitefish Whitewash

Part 2: The case of the missing water quality science gets even murkier

[For Part 1 of this series go here]

Brooke Nodding is the executive director of Coastal Action, a charitable organization that’s been around for three decades with a focus on environmental concerns facing the South Shore region of Nova Scotia. Nodding has also been a member of the Recovery Team for Atlantic Whitefish since 2004 and participated in both iterations of the Recovery Strategy.

Nodding says she was initially invited to the team “to raise the profile of the species in the local community,” but this shifted to partnering with provincial and federal fisheries to identify information gaps. One of those areas was water quality monitoring, and another was trying to address the question of how the species would respond if they were suddenly able to return to the sea.

“We learned that after 100 years of being landlocked, their natural tendencies are still there; they’re still tolerant to salt water and they want to go to sea,” she tells me. Laboratory and hydro-acoustic tracking studies published in 2009 and 2010 show that fish from the Petite Riviere population are still able to make anadromous migrations, that their larval stages can tolerate sea water, and the juveniles actually show a strong preference for it.[1]

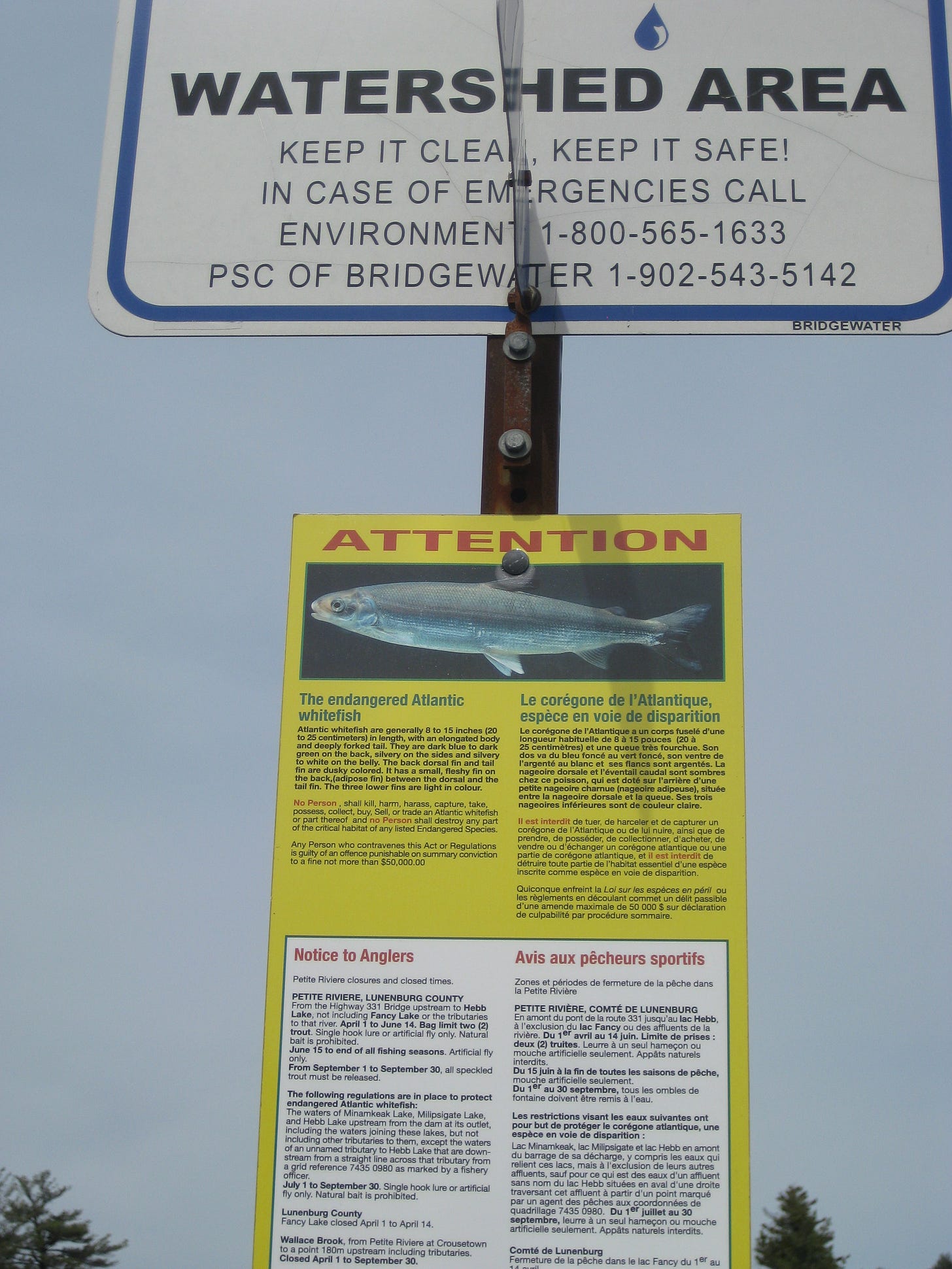

Sign posted next to Minamkeak Lake, one of the last remaining locations harbouring wild Atlantic whitefish. It also happens to be part of the Bridgewater Watershed Area. Photo: Linda Pannozzo

I reached out to Nodding in hopes she might be able to shed light on why the references to the potential negative effects of logging on water quality—made explicit in the first 2006 version of the Recovery Strategy—had gone missing from the “amended” version published in 2018.

Nodding said she was completely unaware that the information had been removed.

“The recovery team has not been as active as it once was. It’s been a frustration to a number of non-government groups that sit on the team,” she says. Nodding says the team used to meet two or three times a year, but during the “Harper era” when “science was cut to nothing,” things “started to change.” The meeting frequency was reduced and they were no longer in person, she says. “Sometimes they were just conference calls.” In the last 3 or 4 years the recovery team, as a whole, has met only once.

Over the years, the size and diversity of the group also dwindled. It took 50 members to develop the 2006/2007 recovery strategy. By the time it was “amended” and finalized in2018, only 21 people were involved (see membership list embedded below).

Nodding says Coastal Action is not in favour of the proposed logging. “We have concerns about the potential impacts to water quality, which would directly impact the health of the Atlantic whitefish, since they live in the water. If they don’t have healthy water, it impacts their survival.”

Nodding also points out there are other species at risk within the proposed cut blocks, including eastern ribbon snake.

“The eastern ribbon snake is a species we also work on, and they would have even more direct impacts because the land is part of their critical habitat.” These semi-aquatic snakes have been listed as threatened under SARA since 2002. Its recovery strategy, published in 2012 was finally “adopted” by the province in 2020. I notice that under “Specific threats,” there is at least a section on “habitat degradation, fragmentation, and loss,” with forest harvesting being recognized as a contributing factor.

Brooke Nodding, executive director of Coastal Action. Photo courtesy Bridgewater and Area Chamber of Commerce

Threats to Atlantic whitefish revised and restructured

At Nodding’s suggestion, I reached out to Kim Robichaud-LeBlanc. She is the lead recovery biologist with the Species at Risk Program of the Department of Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) for the Maritimes Region for various freshwater and diadromous species at risk, including the Atlantic Whitefish. According the DFO, her role is “to develop recovery documents according to national guidance and templates, coordinate engagement and consultation with internal sectors and external partners and stakeholders, and coordinate the various regional internal reviews and approval processes.”

According to DFO media relations—who acted as intermediary between me and Robichaud-LeBlanc—a consultation period took place after the 2006 version was published. The final “amended” version required consideration of “all the comments received during the public comment period on the Species at Risk Public Registry and finalizing the document for regional and national approvals.”

“All revisions were accomplished in cooperation and consultation with all relevant internal DFO sectors, other jurisdictions (e.g., Nova Scotia provincial departments) and external partners and stakeholders,” says the DFO spokesperson. After the comments were taken into consideration, revising the “threats” section of the Recovery Strategy for Atlantic whitefish included “restructuring the section on threats to better separate past and current threats, and updating it to include new information.”

Recall, from Part 1 in this series, the “threats” section in the 2006 Recovery Strategy included a detailed section on “land use practices” and referenced logging and said it can “cause accelerated soil erosion and siltation that can lead to a reduction in the productivity of the aquatic ecosystem and affect the rate and quality of water runoff.” It referenced what appeared to be an important, unpublished study by Llewellyn et al. prepared for the Bridgewater Public Service Commission. That study was removed from the “amended” version of the Strategy.

I have since been able to locate the Llewellyn study, and am now also trying to track down another unpublished study cited within it, which is very specific to the Petite Riviere watershed. I hope to report on both of these studies in Part 3 of this series.

According to the DFO, these references were removed and the “threats” section of the 2018 Recovery Strategy was “revised” to read as follows:

“Poor land use practices can contribute to aquatic habitat degradation. Sectors such as agriculture, residential development, and forestry undertake land-based activities in the Petite and Tusket watersheds. While there are no studies linking these activities specifically to effects on Atlantic Whitefish, and no indications of non-compliance in current practices around the three Petite Rivière lakes, it can be inferred that should common activities not be properly mitigated, they could result in effects to fish and fish habitat.”

Were the risks posed by logging operations to water quality removed and downplayed in the “amended” version because of the comments and feedback obtained during the consultation period?

I asked the DFO if I would be able to view the comments received, including from individuals, external partners and stakeholders, as well as from other jurisdictions, such as other internal DFO sectors as well as Nova Scotia departments.

I was told I would have to file a request for that information through the Access to Information portal.[2]

Done. I will report on the results when received.

Minamkeak Lake. Photo: Linda Pannozzo

‘Plans for logging should raise red flags’

I also contacted the Department of Natural Resources and Renewables (DNRR) about whether they had any knowledge about why the paragraphs that explicitly referenced how logging could impact water quality went mysteriously missing in the “amended” version.

In response, Steven Stewart, media relations with DNRR added this piece to the puzzle:

“Forestry was not determined to be a significant impact on the status of Atlantic whitefish when the species was reassessed by COSEWIC in 2010, so the information would have been deemed to have no longer been relevant to the Species at Risk Act Recovery Strategy or Action Plan in 2018. You would have to contact the Committee on the Status of Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) to find out why forestry was not identified as a threat in 2011… In the case of Atlantic Whitefish, the committee determined that the impact from forestry was negligible. If the impact from forestry changes in the future, the assessment will be updated accordingly and future versions of the recovery strategy/plan will be revised.”

If this isn’t ass backwards, I’m not sure what is. The threats posed by forestry should be included as a precaution, so as to minimize if not eliminate this potential threat so the species has a fighting chance of recovering. If it’s only included after the fact—that is, only "If the impact from forestry changes in the future”— it might be too late.

According to the 2010 COSEWIC assessment, the “contemporary limiting factors and threats” facing Atlantic whitefish are barriers to fish passage, introduction of smallmouth bass, and urbanization impacts such as pollution caused by leaching of domestic waste.” It goes on to report that forestry, mining operations, water quality degradation from agriculture, and acid rain were “lower” sources of risk.

That was pretty much all that was said about forestry operations.

To find out more about what happened when the species was reassessed in 2010, I contacted Dr. John Post. Post is a professor of ecology and evolutionary biology at the University of Calgary. He oversaw the 2010 status report for Atlantic whitefish as the COSEWIC Freshwater Fishes Specialist Subcommittee Co–chair. I explained what I was told by the DNRR—that in the 2010 status report, it was deemed that logging effects on water quality were “not determined to be a significant impact” to the species and as a result, “deemed no longer relevant” in the “amended” recovery strategy published in 2018.

I also told him that more than 100 hectares are currently proposed for logging in the Petite Riviere watershed area — nearly 50 ha of that adjacent to Minamkeak Lake — one of the last remaining locations harbouring wild Atlantic whitefish.

I asked, “Can you tell me what transpired when the 2010 status assessment was being drawn up to result in the decision that the threat posed by logging to the species was minimal? And, did you agree with this determination?”

Post replied:

“I don't recall all of the details that went into the threats assessment for Atlantic Whitefish when we reviewed it in 2010. COSEWIC summarizes and reviews information provided by the jurisdictions, in this case NS DNRR and DFO. Plans for logging in the watershed should certainly raise red flags. Although I am no longer the Freshwater Fishes Co-chair, I anticipate that a reassessment is likely due soon for Atlantic whitefish, and any new threats should be fully considered within this. I have copied your email, and this response, to the current Freshwater Fishes Co-chairs, plus the NS and DFO reps on COSEWIC. Thanks for raising these concerns.”

Wrinkled shingle lichen (centre) was designated a threatened species in 2016 (COSEWIC). Thanks to Frances Anderson, who located it in one of the proposed harvest blocks, it will receive a 100 m buffer if logging goes ahead. Photo: Linda Pannozzo

Atlantic whitefish is a forest-dependent species

John Gilhen was a member of the Atlantic whitefish recovery team in both rounds of its iteration and he was also one of the people listed in the acknowledgements of the 2010 status assessment. Gilhen began his professional scientific career at the Nova Scotia Museum of Natural History in 1963 caring for public exhibits of live fishes. He has since published 90 papers, museum publications, technical reports and the book, Amphibians and Reptiles of Nova Scotia.

When I spoke to him in 2007 and again in 2008, he was the museum’s Curator Emeritus. At the time, I interviewed Gilhen for research I was doing about forest indicators, including the number of known forest-dependent species at risk in Nova Scotia.[3]

Gilhen explained that the criteria for forest-dependence included whether a particular species require forests for food, shelter, breeding or other critical aspects of their life cycles. So that while fish didn’t live in the forests, forests did “dictate” water temperature and water levels and were “very important for most fish species to thrive.”

Gilhen was adamant that both the endangered Atlantic salmon and Atlantic whitefish are forest-dependent because the loss of forest canopy can affect water temperature, sedimentation, and oxygen levels in nearby water bodies, and can therefore harm resident fish.

Indeed, forest canopies can help break the impact of rain on soil, so they slow runoff. Precipitation is also absorbed by decomposing trees and limbs and by soils rich in organic matter. All these functions reduce soil erosion and stream sedimentation and minimize fluctuations in stream water temperatures. Add to this the effects of heavy machinery—causing soil compaction and rutting—and there is plenty to be worried about when it comes to logging in Atlantic whitefish territory.

Despite what the DNRR might say about how contemporary forestry practices pose little harm to fish, there are reasons why we should be concerned that the current regulations protecting watercourses from the ravages of logging are inadequate.

The Nova Scotia Wildlife Habitat and Watercourses Protection Regulations apply to forestry operations on crown, private, and industrial lands. The regulations require a minimum 20m-wide ‘Special Management Zone’ on each side of watercourses greater than 50 cm wide, but they still allow “limited harvesting” within the zone. In other words, the riparian buffer is not a ‘no-enter’ or a ‘no-cut’ zone. The regulations permit logging machinery within the buffer (but not within 7 metres of the watercourse) and allow a certain amount of logging. According to the DNRR: “regulations limit the area of trees and the tree canopy that can be removed.[4]

Studies indicate that a 20m buffer zone, particularly when bordered by a clearcut, is inadequate in maintaining fish habitat.[5] As previously stated, while the cuts or “treatments” proposed in the Petite Riviere watershed are not being called clearcuts, it’s unclear how much forest canopy will be removed if the logging is approved.

According to wildlife biologist Bob Bancroft, “about three-quarters of our wild animal species either depend upon, or prefer, habitats near water.” He says, moose, for instance, need a 50-60m buffer between a clearcut and water before they will even use it. Drawing on a number of studies on the subject, Bancroft says riparian buffers for wildlife should be between 50 and 200m (see his paper on the subject below).

In his 2018 Review of forest practices, Lahey concluded that “the adequacy of the watercourse protection provisions currently prescribed in the Wildlife Habitat and Watercourse Protection Regulations should be independently studied,” and that “the regulations should be amended in accordance with the outcomes of this study.” This doesn’t appear to have happened. In fact, in Lahey’s 2021 evaluation of the implementation of his recommendations he found that the government had yet to review the efficacy of regulations on riparian zones and that it was a matter that needed “urgent attention.”

George Buranyi and Frances Anderson are members of the Bridgewater Watershed Protection Alliance. This stream is part of the Lake Minamkeak watershed—connected through a series of bogs, fens, as well as Caribou Lake. Human activity anywhere in a watershed can have a negative impact on the health of that watershed’s lakes and rivers. Photo: Linda Pannozzo

[Stay tuned for Part 3 where the murkiness turns into pure muck and mire]

[1] Cook, A.M. and P. Bentzen (2009) Restoration of diadromy in an endangered fish: do Atlantic whitefish covet the sea? Haro A., Smith K.L., Rulifson R.A., Moffitt C.M., Klauda R.J., Dadswell M.J., Cunjak R.A., Cooper J.S., Beal K.L., and Avery T.S. Challenges for diadromous fishes in a dynamic global environment. 903- 906. American Fisheries Society. Bethesda, MD; Also: Cook A.M., Bradford R.G., Hubley, P.B. & P. Bentzen (2010a) Effects of pH, temperature and salinity on age 0+ Atlantic Whitefish (Coregonus huntsmani). Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat Research Document 2010\006, 47p.

[2] The DFO spokesperson also said and that some of the comments may be considered protected under Section 21(1) of the Access to Information Act: 21(1) The head of a government institution may refuse to disclose any record requested under this Act that contains:

(a) advice or recommendations developed by or for a government institution or a minister of the Crown,

(b) an account of consultations or deliberations involving officers or employees of a government institution, a minister of the Crown or the staff of a minister of the Crown,

(c) positions or plans developed for the purpose of negotiations carried on or to be carried on by or on behalf of the Government of Canada and considerations relating thereto, or

(d) plans relating to the management of personnel or the administration of a government institution that have not yet been put into operation, if the record came into existence less than twenty years prior to the request.

[3] This section is based on personal communication with John Gilhen, December 7, 2007 and January 3, 2008.

[4] Specifically, the base area of living trees must be at least 20m2 per hectare, and openings in the dominant tree canopy less than 15m. The DNRR itself has conducted the science to know that a 20m buffer is inadequate. In 2008, one (then) DNR study sampled watercourse buffers bordered by clearcuts and found that “the highest concentration of blowdown and soil exposure occurred along the clearcut edge where the trees were most exposed.” The blown down trees were uprooted the vast majority of the time (89 per cent), exposing the soil and changing the structure of the forest floor by “producing mounds and pits” and increasing “the susceptibility to soil erosion.” Soil erosion and sedimentation degrade the quality of lakes and streams, destroy the habitat of aquatic organisms and cause declines in fish populations. The DNR scientists concluded that “to maintain the highest integrity of stream side forest after a harvest…the use of a 30 m [buffer] is favourable in these conditions.”

[5] Moring, J.R. 1982. Decrease in stream gravel permeability after clear-cut logging: an indication of intragravel conditions for developing salmonid eggs and alevins. Hydrobiologia, 88, 295-298.

Barton, D. R., Taylor, W. D., and Biette, R. M. 1985. Dimensions of Riparian Buffer Strips Required to Maintain Trout Habitat in Southern Ontario Streams North American Journal of Fisheries Management 5:364-378

Bancroft, B. 1995. Riverine and riparian habitat: a history of abuse. Proceedings National Habitat Workshop, C.W.S., pp. 121-124

Bancroft, B. 1999. Riparian Forestry Management - For Wildlife and Aquatic Habitat Integrity, Workshop Proceedings - Maintaining Water Quality in Woodlands Operations. Can. Woodlands Forum, pp.1-5.

Excellent. My first job out of Ranger School was working w Bob preparing for the St Mary's River project which was designed to explore the impact of ns forestry on wildlife/riparian zones with the goal of developing guidelines for forestry ops going forward. I've been so frustrated for years to see how the smz's got reduced down to the ineffectual things that they are today. So glad to see Bob keeping the pressure on: the science is clear and obvious.

The name must change from DNRR to Department of Environmental Protection, and the philosophy along with it. DNR has always been about exploiting the environment and allowing big business to rape it. Groups have been battling so many issues for many decades and it seems we take one step forward and two back with each issue. How stupid we are trying to save the Right Whale from extinction, yet our government is allowing cruise ships to ply the waters here and expanding our shipping docks to allow for more and larger ships. Governments will do these things, because they are addicted to the corporate dollar they receive. Individuals can slow and stop much of this by taking a serious look at how they live. Do people really need to go on a cruise? Do they need to buy all that crap from China? Do they need to build a large house or large addition? Sorry, I didn't mean to go on such a rant.