The Ocean's Voice

An interview with Hal Whitehead about the cultural lives of whales and dolphins

Northern bottlenose whales, off the coast of Nova Scotia. Photo courtesy Hal Whitehead

Back in June of this year, eleven long-finned pilot whales beached themselves in Port Hood, on the shores of Cape Breton Island. Eight of the whales died, but as a result of the valiant efforts of a group of teens who were later joined by many local residents, three of the whales were rescued from the rocky beach and returned to the sea. Information from the Marine Animal Response Society (MARS) at the time indicated that the stranded animals were part of a larger grouping of about 30 animals, a mix of males and females, ranging in age, with five of them being nursing calves. As I reported at the time, the dead animals were sent for necropsies, but according to MARS executive director, Tonya Wimmer, the final report has yet to be released.

At the time of the stranding, I was looking for information about what could cause whales to strand in this way. I reached out to Elizabeth Zwamborn, a doctoral candidate at Dalhousie University who runs the Cape Breton Pilot Whale Project, which has been studying the social structure, vocalizations, and collective decision-making of long-finned pilot whales off northwestern Cape Breton since 1998. Zwamborn explained that pilot whales are known to strand themselves, individually or in groups, “from time to time.”

Zwamborn said that while some strandings could be due to “natural causes,” she also explained they could be attributed to hearing loss, from military sonar, seismic testing, and underwater explosions.

Dead long-finned pilot whale on the beach near Port Hood, Cape Breton Island. Photo courtesy Elizabeth Zwamborn.

I wanted to find out more about the these “natural causes” and came across the 2015 book, The Cultural Lives of Whales and Dolphins, by Hal Whitehead and Luke Rendell. Whitehead is a professor of biology at Dalhousie University in Halifax and has spent decades in the field and in his lab exploring the social organization of whales—mainly sperm whales in the eastern Pacific and bottlenose whales in the northwest Atlantic.

Whitehead’s own work has focussed on the behaviour, social structure, population ecology, and conservation of whales. In a word, he is very interested in their culture.

[I reached Whitehead in Halifax by telephone. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.]

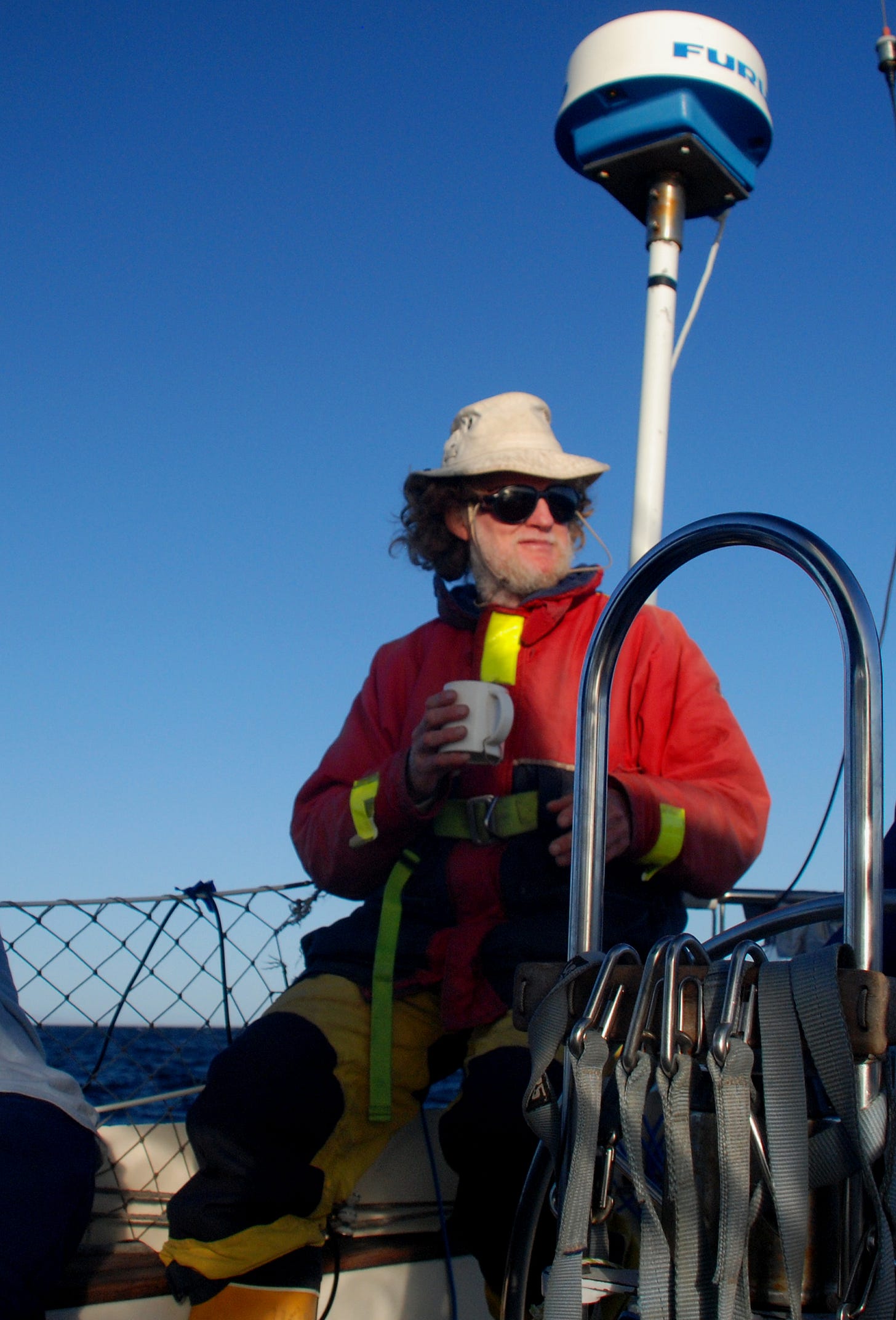

Linda Pannozzo (LP): Before we get into the substance of the book, tell us a bit about how your own experiences “sailing with whales” inspired the book and got you thinking about cetacean culture?

Hal Whitehead (HW): Well, we collect data and then we try and make sense of it and some of the things we collected and some of the patterns we found didn't seem to quite make sense, given the standard way people think about the social structures of other non-human mammals. Then ideas, coming from a very variety of directions suggested we should also think about what animals learn from each other, which of course is pretty obvious really when you think about it. But it had been very much hidden, buried, in the way biologists were thinking about animal behavior, with a few exceptions. So, this could explain some of these things we were seeing in the patterns of data we were collecting. These animals were learning from each other, in other words, they have cultures. Then as we looked further, we started to get better and more definitive evidence for this.

LP: In the book you define culture as “information or behaviour – shared within a community – which is acquired from [other members of the same species] through some form of social learning.” You provide a lot of examples in your book of behaviours or information that are learned and then shared, can you give us an example or two that really stand out for you?

HW: For the whales and dolphins, I think the vocal behaviour is particularly dramatic. You get a bunch of animals who are making the same kinds of sounds and the only possible explanation is that they're listening to each other and then making sounds which sound like the ones they are hearing. That doesn't seem at all controversial, but it is to some people, or it was. I don't think it is so much anymore. And that happens in all kinds of ways. The killer whales on the west coast [of Canada] where the people who know killer whales like John Ford and others can just listen to a very small snatch of the killer whales’ sounds and say, ‘Oh, that's this pod. That’s the other pod.’ Similarly, when we were working on sperm whales in the Caribbean, the graduate students would just listen to a very small amount of the sperm whale vocalizations and say, ‘Oh, that’s this clam or that’s that clan.’ It's very obvious that they have these specific sounds.

Then you’ve got the humpback whale songs changing from year to year. So people again can listen and say, “Oh, that's from a humpback in Bermuda in 1972,” or something like that. So, it’s just like when we’re listening to popular music, you can say, ‘Oh, that's the Eagles or the Sex Pistols from this year or that year.’

Hal Whitehead, professor, Department of Biology, Dalhousie University, sailing with whales. Photo courtesy Hal Whitehead.

LP: I want to ask you a bit more about the whale song. There was a lot on that subject that I learned from your book and one thing that I can't believe I never knew is that only the male humpback whales sing. Can you talk a little bit about what we know about whale song in terms of how this form of communication benefits the male whales?

HW: Vocalizations which have this repetitive pattern to them are only as far as I know, heard from baleen whales, not from the toothed whales and not from all baleen whales, but from most species. As far as we know, in all these species, they are only made by the males, which suggests it's something to do with breeding. This is similar to some aspects of birdsong which have been studied very thoroughly and it's easier to study them because you can put the bird in captivity, you can do playbacks, you can do all kinds of stuff. So, they do know a hell of a lot about birdsong and it turns out that birdsong, when it's made just by the male and in some species that's the case, it usually has one of two of what we biologists would call functions. One is to attract females. The female says, ‘Oh, that's a lovely song. I might pair up with him,’ or [the function is] to repel other males. ‘Oh, there's another male over there and I won't go near that.’ So those are the two usual functions we think of.

The work on whale song has been almost entirely with humpback whales, even though, you know, quite a number of the other baleen whales sing. There’s been lot of work of all kinds, of playbacks, of analyses of sounds, looking at movements of animals and distributions with singing and so on. It's really confusing. You know, neither of those hypotheses is terribly well supported by the evidence and it's led to other hypotheses being produced, including one that the song sort of organizes collaboration among the males or that a song doesn’t actually attract a female to the singer, but it gets her feeling sexy and more willing to mate but isn’t directed to a particular singer.

So those are the kinds of things that are out there and they aren’t well proven either. It's a confusing business. I think part of the problem is that a lot of the evidence for birdsong comes from playback experiments where you playback a song and see what happens and there are two issues with whales. One is, are we really fooling them? And maybe we aren't. In which case they think, ‘Oh, it's just stupid humans pretending to be us’ in which case they aren't going to react as they might to their own song. And secondly, you can't do the same kinds of measurements of the response as you can with birdsong because with birdsong you can measure the hormonal levels of the females after she's been exposed to different kinds of songs or a male after he's been exposed to different songs. We can't do this with the whales.

LP: Since only the males sing and the song is learned, how do the male calves learn the songs since they spend so much time with the mother?

HW: They may learn a bit then, but because the humpback song is evolving very fast, it's not the one they heard when they were a baby that counts. It's the one when they start singing themselves. So, it's learning from peers rather than from parents. So, it's like a teenager typically isn't singing the same songs that their mother was listening to when they were nursing. They're singing or playing the songs that their friends are listening to.

Cover of The Cultural Lives of Whales and Dolphins, by Hal Whitehead and Luke Rendell (The University of Chicago Press, 2015)

LP: You point out in your book that most of our knowledge to date about cetaceans is overwhelmingly concentrated on the iconic whales and dolphins: the humpback, killer, and sperm whales, and the bottlenose dolphins, and you describe some of the ways that whales and dolphins cooperate with each other to feed, for instance. Can you describe what has been observed?

HW: OK, the bottlenose dolphins down in Florida have a system where some of them will drive a bunch of fish towards a barrier set up by the other dolphins. So, they're working together: these are the drivers and these form the barrier and they all get a good meal out of it. So that's one example. There are also the killer whales who routinely share food. So, if a killer whale catches a salmon and there's another killer whale nearby, they almost always share it. ‘You take a bite, and I'll take a bite.’ So, you know, those are a couple of occasions where it's pretty cooperative.

LP: You quote the late Roger Payne—famous for his 1967 discovery of whale song among humpback whales—who said, “[whales] give the ocean its voice.” You also point out that in a study Payne co-wrote that appeared in Science, he described the sounds emitted by whales as “a series of surprisingly beautiful sounds,” and that this was the first and last time they were described this way in a scientific paper. You actually call it the “b-word,” and write, “We as whale scientists know why.” Can you talk a bit about that?

HW: Well, a vital part of the way science works is publication in scientific journals. So, what happens is you do a study, find out something, send it off to the journal, and then the journal sends it to reviewers who go through it sometimes extremely thoroughly, sometimes not. But they really go through it and prune it of anything that they think is a bit dubious. So, generally you can't get the more controversial stuff through. It used to be even the culture thing was controversial and publishing papers on culture were pretty damned hard—culture amongst humans.

Anything that is published has quite a lot of credibility attached to it if it’s gone through the review process. But obviously that weeds out stuff which is a bit marginal and sometimes the marginal bits are the interesting bits, as in this case I would say.

LP: You provided so many examples throughout the book of cetacean behaviours that you believe are evidence of culture. Is there something you learned in your own personal research that really surprised you?

HW: Yes, I think the whole clan business, which was key to the sperm whales. I mean, looking back, it was extraordinary because I was brought up to accept the simplest possible explanation and expect that all sperm whales are basically the same and then to suddenly find there were these major differences between the sperm whale clans that were located [geographically] in the same place, in all kinds of different areas of behavior: how they moved around, how they looked after their babies and so on. Yeah, that was pretty remarkable.

LP: You write that whales and dolphins use hearing to map their environment and their social world, and that their sonars give them a detailed picture of their surroundings, but that this incredible hearing has also made them very vulnerable to anthropogenic noise. Can you tell us about “typical” and “atypical” mass strandings and what we know about what causes mass strandings of cetaceans?

HW: Well, there's certain things that have become clearer and some bits which really haven't become much clearer. Whales will turn up on beaches from time to time and sometimes the dead are in very bad shape and sometimes they seem pretty healthy, so people try to make sense of this. The ones that are dead or in very bad shape can usually be explained: something nasty has happened to them or they've just died and they washed up on the beach. So that part is fairly straightforward. Where they wash up on the beach and they appear healthy is more of a puzzle because they're aquatic animals and they shouldn't be on beaches. There are a few occasions where animals can catch food on beaches by being very careful, like killer whales in the southern hemisphere or bottlenose dolphins in Charlotte Bay. But yeah, mostly they should not be on land.

One way to look at this is, is to ask is it solitary? And typically, it isn't. If they're healthy, they don't tend to end up on beaches by themselves, and if they are, they probably aren't healthy in some way that isn't immediately obvious. Sometimes they come in groups and you find several of them together and sometimes this happens over large spatial scales, over tens or hundreds of kilometers. These are the ones known as atypical mass strandings and these have really only been observed since about the 1960s and they do seem to be related to sounds humans make and that these sounds for reasons which I don't think are fully clear—and I’m not up on all the latest on this aspect—have either directly or indirectly caused the whales to run up on the beach: so naval sonar, oil and gas [seismic], and so on. That used to be a very controversial argument, but I think it's pretty much accepted now. For instance, navies are becoming a bit more careful about where they make loud sounds.

The third kind [of stranding] is where the whales come up in the same place at the same time, and there's a bunch of them. These are the typical mass strandings and they've been happening—I think Aristotle mentions them— so from way, way back. These are still not very clear. People have been trying to figure out why for a long time and there are certain things they found which indicate something about what might be going on. For instance, they often happen in places where the depths are very confusing. So, there's shallow banks or big tides, that kind of thing. They often happen after storms, magnetic anomalies, and so on. They happen with social species which spend a lot of time with each other. Typically, if this happens and you pull off some of the healthy ones, they will come straight back on the beach unless you get a whole lot off the beach. Then they may go off together and survive. This suggests there's some sort of social imperative to be with each other and to be on the beach together.

So it looks like it's related to the social life of the whales. There may be some there who are sick and the others just stay with them and they end up on the beach. But we don't know for sure. It's very confusing. I think it’s related to cultural norms. So, what the young animals learn is the way to behave and the way to behave is to always stick with your buddies, and that involves if they're sick and they end up on the beach, you go up on the beach with them. I'm not sure. But we do know that cultural norms leads humans do things which don't make a lot of sense for prolonging your survival, like joining armies, or some suicide cult or whatever.

Mass stranding of long-finned pilot whales in Cape Breton, Nova Scotia. Photo courtesy Elizabeth Zwamborn.

LP: As you know, back in June of this year, eleven long-finned pilot whales beached themselves on the shores of Cape Breton Island, in Port Hood—eight died and three were re-floated by local residents. Information from the Marine Animal Response Society indicated that the stranded animals were part of a larger grouping of about 30 animals, a mix of males and females, ranging in age, with five of them being nursing calves.

The dead animals were sent for necropsies and the final report hasn’t been released yet but I understand there are indicators that it was a mishap and that the animals that died were all healthy. This wasn’t the first time there was stranding of long-finned pilot whales in this area – there was a similar stranding in 2015 in Judique, and in 2014 there was another one near Summerside PEI. I realize I’m asking you to speculate, but what do you think could cause pilot whales to strand in a situation like this?

HW: Well, we don't really know, but a lot of the elements that seem to be common to these kinds of events are there. These are in Cape Breton and there is a substantial population of pilot whales just off the coast. So, there are pilot whales in the area. Secondly, there are places with beaches, which obviously are more likely to have such strandings than cliffs. These seem to be the typical strandings—they're not obviously related to human sounds, as far as I know. So, we don't really know what's going on, but a lot of the elements that are often found with these [typical] events are present there.

LP: In the case of a “typical” stranding, which this incident in Cape Breton could have been, why doesn’t the individual whale’s instinct to protect itself and save its own life override what you call “the social cohesion imperative?”

HW: Well, that's really interesting. I don't know. But my thought about this is that the social cohesion instinct is actually for these animals much stronger than it is for most other animals, including humans. So, we know that we can culturally move humans away from the ‘protect ourselves’ to ‘do what the group thinks is right,’ even though it may be very dangerous to ourselves. That obviously happens in military situations where soldiers are strongly taught and learned that you don't run away when things get nasty. You stand there and fight back, which is not the most sensible thing from an individual perspective. But it does make sense from the army perspective because if all the soldiers ran away every time things got nasty, the army wouldn’t do very well. So, we know that can happen. My thought is that with the whales and dolphins, that happens much more strongly. For them, the drive to do the social thing is more important than individual survival.

LP: Could you also touch on the difference being matriarchal and matrilineal societies and if that has anything to do with some of the stranding events.

HW: It could do. Matrilineal means you're with your female relatives. You live your whole time with or most of your time with your female relatives. So, a matrilineal society is where sisters and mothers, grandmothers and daughters all stay together and there are some matrilineal human societies, although it's typically not the case. We’re more patrilineal, where the males stay together. There is strong evidence that a number of whales and dolphins especially the bigger toothed whales—the sperm whales, the killer whales, the pilot whales and a few other species—live in matrilineal societies, living with their female relatives.

A matriarchal society is one in which one of the females is the boss. Often but not necessarily it’s the oldest female: the grandmother or the great grandmother. That's what you find in elephant societies and also in some human societies too. There is relatively little evidence that whale and dolphin societies are matriarchal. So even though they may be matrilineal, it's not super clear in any of them, as far as I know, that there's a particular female who's calling the shots in the same way that the older female elephant calls the shots. So, the evidence, I think, points to things being what you might call more democratic. They sort of figure it out among themselves rather than waiting for great granny to tell us what to do.

LP: In a stranding event, it’s not like one of the females leads the way or something like that?

HW: Well, that would be the matriarchal hypothesis and I don't think there's a whole lot of evidence for that. So, for instance, it seems more that if you can get a majority of them off the beach at the same time, then they will swim off. So, it's more about numbers than a particular individual.

LP: You also write about how whales, like humans and elephants and chimpanzees, interact with their dead. Why is this significant?

HW: It's significant in suggesting that the social world doesn't end at death and includes—at least in some way—animals who have died, and that speaks to, I think, a more complex society with a history, with memory and so on, rather than one where you interact with who’s around you right now, and when they've gone, well, that's it, maybe they'll come back and maybe they won't. There's other evidence, such as dolphins remembering each other over decades where they haven't seen each other or heard each other. So, yes, it suggests these societies are long term.

LP: Could it point to a spirituality or something along those lines?

HW: Well, it could do that, yes, absolutely.

LP: If whales and dolphins have culture—which your books very strongly argues for—then are there ethical and moral considerations in our treatment of them that go beyond maybe other species?

HW: I don't think that argument immediately follows from one another because why should culture move a species along the ladder of how we should treat them? But I think that these become philosophical questions and the philosophers will consider the issue of personhood and the idea is that a person is treated differently from other things. Then the question becomes, what is a person? One definition is just humans. But then you get into issues like, is a fetus a person? That's obviously a big issue at the moment. Is someone who's brain dead, a person? And then there's clear evidence of other things being treated as persons. So, for instance, in US law, and I think in many other countries, corporations are considered persons legally. Then in other systems, rivers are being treated as persons, I think in New Zealand and India.

So, it isn't obviously clear what is a person and what isn't a person. Philosophers would argue that the attributes of some non-humans are such that they fit all the criteria for personhood and when you do this, one of the potential criteria for personhood is culture: that individuals interact with each other and learn from each other and that governs how they see and use the world and how they live their lives. So, in that sense, culture is an important contributor to the assignment of personhood to these animals and that has a huge influence on how they are treated, because if they can be given all the rights of a human person, that's a big deal.

so many unknowns about whale behaviour...leading to questions about what it is to be a person

Enjoyed the interview !

Great interview! You asked some fine questions!