FOI on the Downgrading of the Wetland Conservation Policy

About a month ago I reported that I had filed a Freedom of Information request for the information about the downgrading of the Wetland Conservation Policy. You may recall, an internal directive within the provincial Department of Environment has functionally delisted thousands of hectares of Wetland of Special Significance, and the government is not being transparent about it. I filed a request asking for the directive, essentially, and any communications leading up to it. A few days ago I heard back from the Information Access and Privacy Services administrator that they need more time to process my request, 30 more days in fact, because “a large number of records is requested or must be searched and meeting the time limit would unreasonably interfere with the operations of the public body.” I’ve heard that one before. Thing is, if they would just answer a journalists’ questions, it would save them all that time.

But it’s not about time. It’s about keeping these internal decisions away from the prying eyes of the public.

Vernal pool near Herring Cove. Photo: Wetland Conservation Policy

Two part series featuring a wide-ranging interview with psychiatrist and anti-depressant expert Dr. David Healy.

In 1999, Dr. David Healy, a professor of psychiatry at Bangor University in Wales, accepted the post of director of the mood and anxiety disorders programme at the University of Toronto’s Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH). The lucrative position and professorship was set to begin in 2001, but in November 2000, Healy delivered a lecture to some of his colleagues in which he criticized psychotropic drugs, arguing that selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors such as fluoxetine (Prozac), manufactured by Eli Lilly, could lead to suicidal thoughts and were probably being overprescribed. Two weeks later, Healy’s job offer was rescinded.

Around the time this was happening to Healy, I was working at Dalhousie University as the Executive Director of the Nova Scotia Public Interest Research Group, spending a lot of time researching the new alliances that were forming between industry and universities. The new “partnerships” were becoming ubiquitous features of campuses across the continent and were not only a threat to academic independence but also to unimpeded inquiry. In a piece I wrote in 1999 titled, “Masters of the University,” I interviewed fisheries scientist, Jeffrey Hutchings, who said, “The greater we entwine ourselves with industry, the greater the degree we potentially subvert academic freedom, the freedom to critically examine or analyze the workings of industry and government.”

Healy ended up suing the UofT for breach of academic freedom and won.

I have been following Healy and his work ever since. He’s been involved as an expert witness in homicide and suicide trials involving psychotropic drugs, and in bringing problems with these drugs to the attention of American and European regulators.

I recently had the opportunity to speak with Healy at length about what happened to him and what he thinks about the state of pharmaceutical “science” more than 20 years on, and the implications of putting our faith in what has become a very secretive industry.

The first in a two-part interview series, will go live (I hope) next week.

Dr. David Healy

A book submission about the pandemic, like a time capsule

A few months ago I was approached by Kent Martin to collaborate on a book about the pandemic. For those of you who don’t know Kent or his work, he has spent the last 50-years as a filmmaker, mostly for the National Film Board of Canada. Many of his films are award-winning and many have played in film festivals all over the world. The feature documentary Westray was short listed for an Academy Award. Kent is retired from the National Film Board, but is still making films, having produced/ directed more than 100 of them over the course of his career.

During the pandemic, Kent grabbed his camera and headed into the streets as a witness to what was happening, and took hundreds if not thousands of photographs. When he approached me, he said he originally had a book of photography in mind, but now wanted to collaborate with me, and include a number of my articles and essays — drawing on my work and research on the subject. The idea was to create a chronological compilation of photos interspersed with essays — essentially to create a time capsule that would span about 3 years, starting in early 2020.

When I returned to all the writing I have done on the pandemic, I was surprised to discover that I had written more than 80,000 words — a 200-page book is about 50,000-60,000 words. I guess I had a lot to say! Over the last many weeks, in addition to putting together a submission for publishers, I’ve been trying to work out how I will pare it all down to roughly 40,000 words — with chapters separated by uninterrupted sections of Kent’s evocative photos. The process will be time consuming and difficult on so many levels.

One of the things we felt was important for each of us to include in our book submission was what we saw as the “purpose” for the book, from a personal perspective. This is what I included in the submission:

When the pandemic was first declared by the World Health Organization on March 11, 2020, I contributed regularly, for four years, to a local “adversarial” online news outlet. At first, like everyone, I was shocked when less than a week later, Dr. Robert Strang, Nova Scotia’s chief medical officer of health and Premier Stephen McNeil announced that bars would close, restaurants were limited to take out and delivery, and that gatherings would be limited to fewer than 50 people. The subsequent state of emergency tightened entry points into the province, and required that people coming in “self-isolate” for 14 days. By the end of March, schools were closed and social gatherings were limited to a “bubble” of 5 people. It was impossible to be prepared for the scale and scope of what was to follow.

The restrictions meant that both my husband—a teacher—and my daughter—a high school student—would be working and studying from home. As a freelance journalist, this was something I was already accustomed to. At first, when we were told it would take two weeks to “flatten the curve,” it felt a bit like a vacation. We expanded our vegetable garden and baked bread. But as we all know now, the state of emergency didn’t last two weeks, but would continue for more than two years. Eventually the public health response would include vaccine mandates and policies that barred the unvaccinated from participating in civic life, despite reports of waning efficacy and breakthrough infections, creating deep fissures in families, friendships, and communities.

I started questioning whether public health policies were evidence-based, whether they were having the intended effect of slowing transmission and keeping hospitals from being overwhelmed, and what their collateral damage might be. But challenging the narrative came at a cost. I began to feel very isolated and sensed that questioning public health policies was becoming verboten, even among my colleagues. I did not want to be bound by what I saw as the dictates of groupthink, or have anything to do with an increasingly divisive, hateful and polarizing rhetoric. Not only that, reporters were becoming stenographers, co-creating a narrative with the government, and avoiding the question that every journalist must always ask, “is what they’re saying true?”

Kent and are in the process of trying to find a publisher. I will keep you posted if we manage to find a taker. Your suggestions are welcome!

Photo: Kent Martin

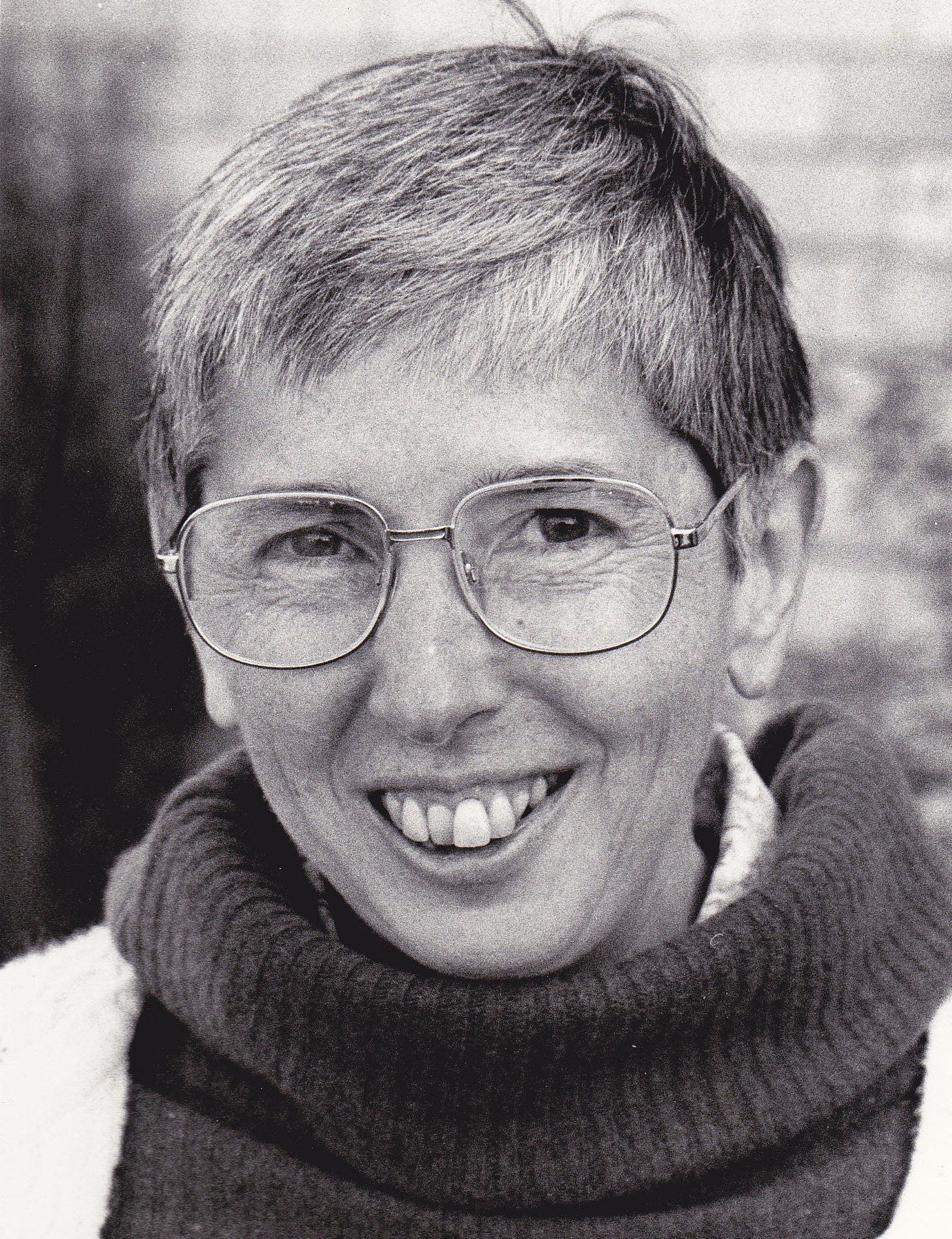

“Making the victims visible” — an upcoming article (or maybe a biography) about Rosalie Bertell

I had the honour of meeting Rosalie Bertell many years ago — on Frederick Street in Sydney, Nova Scotia when I was helping Elizabeth May with some research for her book about the tar ponds, one of the worst toxic waste sites in North America. I later interviewed Bertell for a piece I wrote for The Coast about workers who had radiation exposures at the Phalen mine.

Bertell died in 2012 but her legacy lives on. She was a feminist, scientist, author, peace and environmental activist, and is probably best known for her work raising awareness about the health hazards from radiation. In the 1990s, Rosalie shifted her focus from radiation and nuclear weaponry to what has been described as “radically new American war strategies that involve the planet itself as a weapon,” and in 2001 she published what would be her last book, Planet Earth: The Latest Weapon of War. In this book she raises very worrying, but legitimate questions about how war and military testing are disrupting the natural patterns both on earth and in the protective layers of the atmosphere. This is an area I’d like to explore further in my research.

I’ve been busy interviewing people who knew Bertell. This will be a long-term project, but I hope to publish an article here in the weeks to come.

Rosalie Bertell, April 4, 1929 - June 14, 2012

Hi Linda, please don't miss Dr Bridle's lates substack post providing us with the Can-Phizer agreement.

Good l=uck with this! There is a publisher in the states that has been publishing dissenting views. I will look it up and send it to you.

Dr. Healy is indeed a brilliant gem. Looking forward to your conversation with him. Regrettably, I believe he has had to leave Canada because of his fearless views on Covid shots,etc. Hope I’m wrong.