Emergency orders were unlawful, unconstitutional, and did not meet the legal threshold, concludes the Canadian Civil Liberties Association

In its final submission to the Public Order Emergency Commission (POEC), the The Canadian Civil Liberties Association (CCLA) represented by Cara Zwibel and Ewa Krajewska—stated in no uncertain terms that the emergency orders were unlawful, unconstitutional, and did not meet the legal threshold of the Emergencies Act.1

For nearly 60 years the CCLA has worked to protect and promote the rights and freedoms of people in Canada and “guard against overreach by state actors and hold those actors accountable for violations of constitutionally protected rights.”

The invocation of the Emergencies Act on February 14, 2022 was seen by the group as one such violation.

Recall, the federal government declared a public order emergency in response to a blockade that began on January 28 when a “freedom convoy,” that included a number of big rigs, converged on Ottawa’s downtown core in opposition to the federal government’s requirement that Canadian truck drivers crossing the US border be fully vaccinated to avoid testing and quarantine requirements.2 The protests also expanded to include border blockades at the Ambassador Bridge between Windsor and Detroit, at Coutts, Alberta and at Emerson, Manitoba. As well, demonstrations erupted spontaneously across the country, including here in Halifax, where protesters expressed frustration and anger about ongoing public health measures, including lock-downs, mandatory masking, school closures, and provincial vaccine policies that prohibit the unvaccinated from accessing non-essential services.

As previously reported here, here, here, and here, when the Act was invoked, the CCLA questioned the legality and constitutionality of doing so, and argued that the Ottawa and border blockades did not meet the extremely high threshold laid out in the Act.

The invocation of the Act automatically resulted in the establishment of the POEC, an inquiry to examine what went into the government’s decision-making at the time. The Commission, led by Justice Paul Rouleau, took place from October 13 to December 2nd and granted the CCLA “standing” in the inquiry, giving the organization the ability to cross-examine witnesses.

Ottawa protests, 2022. Photo from Wikimedia Commons

What constitutes an ‘emergency’ under the Emergencies Act?

In covering the POEC, my aim has been to shine a light on the CCLA assessment of whether the federal government acted within its legal authority in declaring a public order emergency, which is specifically defined as “an emergency that arises from threats to the security of Canada and that is so serious as to be a national emergency.”

Section 3 of the Emergencies Act defines a “national emergency” as:

[A]n urgent and critical situation of a temporary nature that seriously endangers the lives, health, or safety of Canadians and is of such proportions or nature as to exceed the capacity or authority of a province to deal with it, or seriously threatens the ability of Government of Canada to preserve the sovereignty, security, and territorial integrity of Canada, and that cannot be effectively dealt with under any law of Canada.3

In its final submission, the CCLA points out that the evidence and testimony heard during the inquiry demonstrate that the provinces had both legal authority and operational capacity to address the situations. In fact, in both Windsor, Ontario and Coutts, Alberta, police were either in the process of dismantling or had fully dismantled the border blockades before the Emergencies Act was invoked, “without the need for extraordinary powers,” they write.

The CCLA argues that the Commission heard evidence that “the struggles” to remove the blockade in Ottawa “were about coordination, communication, and resources, not an absence of legal authority.”

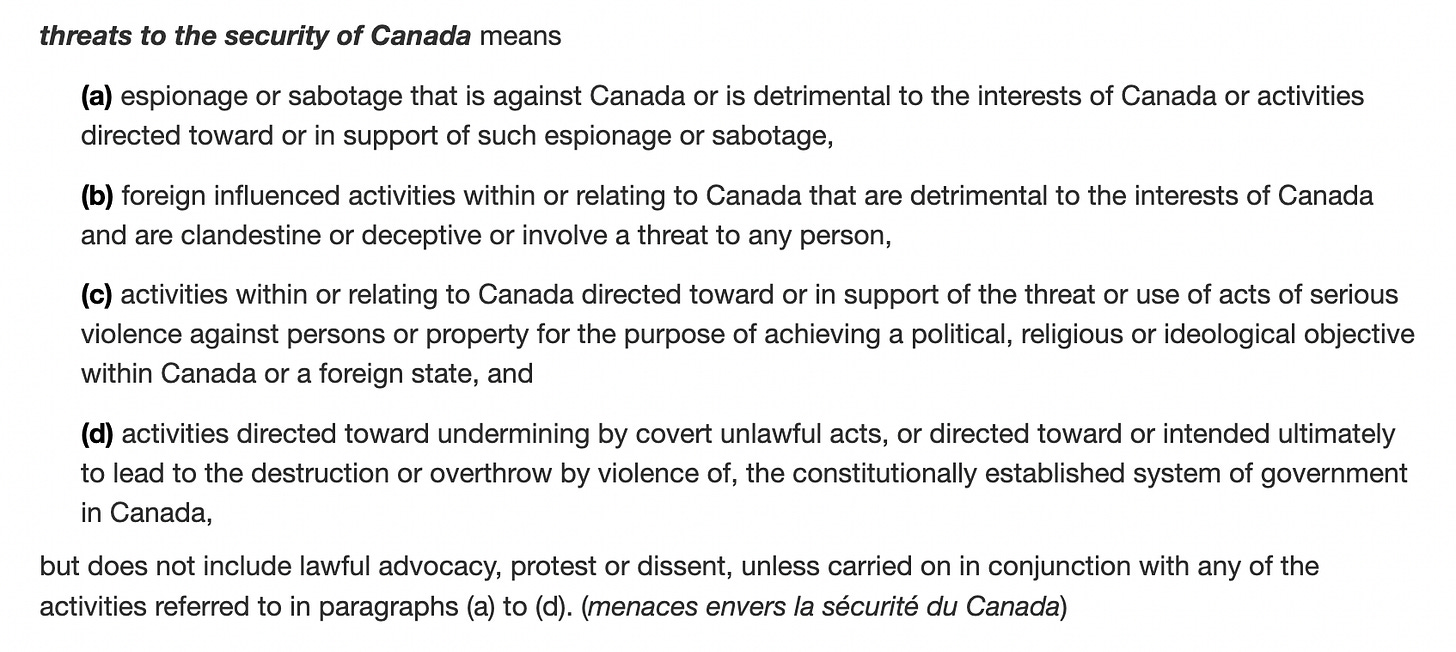

The CCLA points out that the Act is also very specific, stating that “threats to the security of Canada has the meaning assigned by section 2 of the Canadian Security Intelligence Service Act” (see detail below).

In other words—and this is a crucial point—the CSIS definition of “threats” is directly incorporated into the Emergencies Act.

Screen shot: “Threats to the security of Canada,” from Section 2 of CSIS Act.

Based on the CSIS Act definition, the CCLA argues the Ottawa and border blockades did not constitute such a threat and therefore did not meet the definition of national emergency.

Drawing on testimony by intelligence officials from CSIS and the Ontario Provincial Operations Intelligence Bureau (POIB)—the CCLA say the evidence heard by the Commission “discloses that there was no such threat to the security of Canada” and that “the government improperly relied on a different and significantly broader interpretation of the legal threshold.”

Specifically, the CCLA point to the testimony of CSIS director David Vigneault who stated, “At no point did the Service assess that the protests in Ottawa or elsewhere… constituted a threat to the security of Canada as defined by… the CSIS Act.”

Similarly, witnesses from the Ontario Provincial Police (OPP) and the OPP’s intelligence bureau (POIB) testified there was no specific, credible intelligence of a violent threat or a threat to the security of Canada, and that any concerns that the protests might serve as a cover for a “lone wolf” attack were “speculative” and not grounded in any evidence.4

As I’ve previously reported, the Commission heard from Jody Thomas, the prime minister’s security and intelligence advisor, who told the Commission that she was aware of CSIS’s conclusion that the Ottawa protests did not meet the threshold necessary to declare a national emergency but she felt the intelligence agency’s mandate needed to be “modernized.” Thomas said the definition of a “threat to security of Canada” under the Act should change to reflect the times and the determination of what these threats entail should be made in policy rather than in legislation, and should be crafted by Public Safety Canada, the department in charge of public safety.5

In other words, the government believed the definition should be changed and acted based on what it thought the threshold should be, not on what the threshold currently is.

CCLA lawyer Cara Zwibel cross-examines Jody Thomas, the prime minister’s security and intelligence advisor, November 17, 2022.

Legal threshold for declaring a public order emergency not met, says CCLA

While the CCLA does not dispute that the situation in Ottawa was both “urgent” and “critical,” they say, “it is less clear whether the threshold of seriously endangering the lives, health or safety of Canadians was met.” The CCLA write:

The blockades were extremely disruptive in the communities where they took place and gave rise to real harms to residents and businesses. Evidence heard by the Commission attested to the harm and fear that residents in Ottawa experienced, and the input that the Commission received from the public also provides insight into the sense of fear and intimidation that many residents felt – although it is significant that there was a wide diversity of views and perspectives on the protests.

In that last line, the CCLA is referring to the Commission’s summary of nearly 9,500 Public Submissions, which clearly indicate a wide diversity of views—both positive and negative—relating to the protests and the measures taken for dealing with them.

The CCLA also notes that based on the evidence presented to the Commission, the operational plan that was eventually implemented and successfully cleared the downtown Ottawa protests “was developed relying solely on common law and ordinary statutory authorities.”

They argue that the issue was not that the pre-existing legal authorities were inadequate to clear the protests, but that there was a lack of “coordination, planning, and resource” deployment.

To illustrate, the CCLA point to the measures put in place when Ontario declared an emergency on February 11, 2022. These “were broad and attached significant consequences to failure to abide,” say the group, but the federal government didn’t wait to see the impacts on the ground, declaring its own national emergency just three days later.

“Freedom convoy,” downtown Ottawa, Wikimedia commons, January 31, 2022.

Description of Canada by US investor as ‘banana republic,’ ‘heart-stopping’ for Chrystia Freeland

Economic disruption was one of the federal government’s key justifications for invoking the Act. Commission witnesses, including Deputy Prime Minister Chrystia Freeland, testified that the blockades, particularly at the border crossings, were having a sizeable impact on the Canadian economy. Freeland testified that she was concerned the blockades were undermining the confidence of prospective investors and that there would be long-term economic impacts if Canada was not seen as a safe country in which to invest.

At one point in Freeland’s testimony, she responds to text evidence, where a Canadian bank CEO writes that a prospective investor in the US referred to Canada as a “banana republic”—a term used to describe an unstable economy. Freeland tells the Commission that when she saw the reference at the time of the protests, “it was a heart-stopping quote for me.”

Freeland:

A lack of business investment translates into Canadians not having jobs and Canadians not having jobs that pay enough… I had a duty of stewardship…I have to protect Canadians. I have to protect their wellbeing…. The job of finance minister is to make sure Canadians have a good life.

Freeland continues:

[What] I was really worried about was that as this goes on, every single hour, more damage is done to American confidence in us as a trading partner and more damage is done to us as an investment destination.

According to Freeland, the protests threatened Canadian jobs.

“My profound conviction was that Canada was in economic jeopardy,” Freeland told the Commission.6

But according to the CCLA, economics should not trump rights and freedoms.

“There is a real danger in allowing the government to make economic considerations a priority over democratic values and fundamental freedoms of assembly and expression,” the CCLA write.

CCLA lawyer Ewa Krajewska cross-examines Deputy Prime Minister Chrystia Freeland, November 24, 2022.

It’s also important to note that while being cross-examined by CCLAs Krajewska, Freeland explained that part of the reason she did not see the Ottawa protests or border blockades as legitimate forms of protest was because the Canadian government was democratically elected and “acting on policies we had campaigned on just that summer, so it was a fresh democratic mandate."

"There was no lack of transparency with the people of Canada and people who disagreed with those policies were holding the country's economy hostage and that was not appropriate,” she told the Commission.7

The emergency orders were ‘unlawful and unconstitutional’, says CCLA

In its final submission, Zwibel and Krajewska, on behalf of the CCLA, state that the prohibitions on public assembly were “unjustifiably broad” because they didn’t just target “specific protests or geographical areas,” but instead downloaded “too much discretion to law enforcement,” to enforce the measures.

“It is likely that labour strikes and other forms of typically lawful and safe protest activity were prohibited while the emergency orders were in place,” they write.

The CCLA also took significant issue with the freezing of the financial accounts of “designated persons,” stating they were “too broad.”

According to the CCLA, by February 23, 2022, when the declaration of emergency was revoked, the RCMP had disclosed that de-banking or freezing involved total of 57 “entities” (and 257 financial products, including personal and corporate accounts and credit cards) to financial institutions, including individuals and owners or drivers of vehicles involved in the blockades, and 170 Bitcoin wallet addresses to virtual asset service providers.

“As a result of accounts being frozen, money that families use to buy groceries, pay their rent, and pay child support was cut off. Notwithstanding the government’s intentions, the impact of freezing the accounts spread beyond those participating in the blockades,” say the CCLA.

For instance, in his testimony, convoy organizer Tom Marazzo, who lost his job at Georgian College because he was unvaccinated, told CCLAs Ewa Krajewska that when his accounts were frozen, his family “luckily had cash in the house” to cover the costs of his son’s heart medication for myocarditis.8 All of Marazzo’s accounts were affected, including his joint accounts, affecting individuals that were not involved themselves in the protest. He also said he was never notified by his bank that his accounts and cards would be frozen.

Similar stories were told by other protest organizers whose accounts were frozen.

The CCLA final submission states:

The emergency orders that came into force following the declaration were unnecessarily broad and consequently unconstitutional. These orders prohibited a wide range of public assemblies, allowed the government to compel individuals to provide services, and allowed for the freezing of personal assets with no notice and no due process. The orders ultimately relied on law enforcement and financial institutions to use their discretion and engage in selective enforcement to avoid the worst consequences of their over-breadth.

Protesters supporting “Freedom Convoy” in downtown Halifax, February 12, 2022. Photo: Linda Pannozzo.

Lawful versus unlawful protest

The right to protest “is fundamental to a vibrant liberal democracy,” says the CCLA, and the government “bears the onus of justifying restrictions on these rights as reasonable and proportional.”

The group points out, however, that during the inquiry there wasn’t a clear consensus on the difference between a lawful and an unlawful protest.

It is worth noting that while the “Freedom Convoy” protests included prolonged engagement in unlawful behaviour (in the form of illegal parking and blocking of roads, for example), it is not at all uncommon for protests to violate such laws, although usually for a more limited period. Even without the presence of vehicles, large groups of people protesting on foot will often lead to the blocking of roads and may contravene provincial or municipal traffic rules…. The CCLA submits that the mere contravention of such laws does not necessarily render a protest ‘unlawful.’

The civil liberties advocates point out in their final submission that there were competing perspectives presented during the inquiry on what constituted an “unlawful” protest. For some of the protester witnesses, acts of violence would have tipped the protest into unlawful territory, while for others, a protest was unlawful if it was disruptive to residents and businesses. Others believed that the police have “a right to dictate the time, place and manner of protest activity.”

The CCLA:

[B]oth extremes must be rejected. The right to protest (which incorporates both freedom of expression and peaceful assembly) must be given a large and liberal interpretation and that police have a duty to facilitate protest activity while protecting public safety. The law must recognize that, very often, a protest will only be effective if it serves to disrupt communities or upend the status quo. These are features of protest that help protesters draw public attention to their cause and put pressure on decision-makers to take their actions seriously.

While there were unlawful activities on the part of some protesters, these “must not necessarily or automatically be attributed to an assembly as a whole… and render the assembly itself not protected by the Charter,” argues the CCLA.

“The right to peaceful assembly has a broad scope, with narrow exclusions for violence and threats of violence.”

This view was echoed during the Commission’s round table discussion on Fundamental Rights and Freedoms at Stake in Public Protests and Their Limits.

Professor Emeritus Jamie Cameron, from the Osgoode Hall Law School, and long-time civil liberties advocate, noted that if participants in a public protest engage in criminal activity, they are responsible for their actions. In other words, the acts of individuals should not “taint the assembly, unless they define the assembly.” Cameron says, based on international jurisprudence, “peaceful assembly is protected up to the point of violence.”

Professor Brian Bird from the Peter A. Allard School of Law at the University of British Columbia made an important point that is very relevant to the Ottawa protests:

Perhaps the greatest obstacle to appreciating the democratic value of protest is our own personal opinions on the aim or cause of a particular protest. When we disagree with the viewpoint animating the protest of the day, our opinion of protest as a form of democratic participation may also diminish. And the reverse also might be true. When we agree with the complaints of the protestors, our affinity for protest itself may increase as well… It takes a major dose of even-handedness and tolerance to express support for peaceful protest, even when we vehemently disagree with the reason for this or that protest, or the views that the members of a protest hold. And yet in Canada, this ideal, this even handedness and tolerance, seems to be our aim in a free and democratic society committed to maintaining a public square that is open to all its citizens and apart from exceptional circumstances, the unhindered expression of their core convictions.

The Commission also heard some evidence highlighting the concern that the police gave the “Freedom Convoy” protesters “special treatment and that protesters for causes like Black Lives Matter or Indigenous rights have been treated harshly by comparison.”

The CCLA agrees that while there is evidence of systemic discrimination in Canada’s criminal justice system and in many Canadian law enforcement institutions, and while this backdrop is important “context” for the Commission to consider in assessing the actions of police, “the duty of police to facilitate safe protest activities does not change.”

State’s “thirst” for greater intelligence capabilities needs to be approached with caution, says CCLA

According to the CCLA, an important “theme” that emerged during the Commission “was a desire for various law enforcement and government agencies to have greater access to intelligence and improved intelligence capabilities.” The group says this “narrative about the need for greater surveillance” was being associated with the Ottawa protests.

A number of witnesses addressed the “need” for more surveillance including Judy Thomas, the Prime Minister’s National Security and Intelligence Advisor. As well, staff from the Prime Minister’s office—Katie Telford, Brian Clow, and John Brodhead—indicated that while they were receiving briefings from law enforcement throughout the blockade, there “was a thirst for more,” write the CCLA.

At the same time, Superintendent Patrick Morris, the Commander of the Ontario Provincial Operations Intelligence Bureau (POIB) told the Commission that while he saw media accounts and “online rhetoric” asserting there was foreign influence, criminal activity, and threats of violence, he was not aware of “any intelligence that was produced that would support concern in that regard.”

The CCLA writes:

Although some witnesses referred to the need to find ways to effectively monitor “open source intelligence” the CCLA submits that this is a more palatable way of describing what is in reality a system of mass surveillance. Open source monitoring means surveilling the day-to-day communications of the nation, including all of the banal, funny, silly, tragic, intimate and ultimately personal messages we post online for the purposes of our social connection with others… The routine and indiscriminate monitoring of the communications of people in Canada fundamentally alters the nature of the relationship of individuals to the state in a democracy. We typically assume that we are presumed innocent and can participate in society (which is increasingly not just possible to do online but often necessary) without ubiquitous state surveillance. The kind of mass surveillance proposed by some witnesses changes things dramatically and can have a chilling effect on individuals and their willingness to engage with others in online spaces.

“Moving to a society where mass surveillance by the state is normalized shifts our expectations and risks significant erosion of our privacy rights,” say the CCLA. The group also significantly notes, “the surveillant gaze of law enforcement and other state actors is often disproportionately directed at already marginalized minority groups (Indigenous and racialized persons, for example).”

Part of the government’s justification for saying there is a “need” for greater surveillance involves what’s perceived as a problem of mis- and dis-information online. Indeed, while the Commission was ongoing, the federal government has been working toward new and worrying cybersecurity legislation (Bill C-26) that the CCLA and others say is seriously flawed and lacking in safeguards against abuse by state actors.9

Part of the Commission’s mandate was to address the issue of mis-and dis-information revolving around the protests but the issue was not explored in any detail during the testimony phase of the inquiry. The Commission did hold a policy roundtable on the subject, which demonstrated the “nuances and challenges in tackling this issue,” write the CCLA.

It is worth noting that although misinformation and disinformation may have played a significant role in motivating some protesters, the government’s own use of social media to quickly disseminate information or to amplify its narrative can similarly result in the spreading of mis- and disinformation. Any attempt to address the problems of mis- and disinformation in online spaces comes up against concerns about robust protection for free expression and difficult questions about whether or when state actors can or should be the arbiters of truth.

The CCLA cautioned the Commission not to make any substantive recommendations on what the group describes as a “complex policy area.”

We can expect to see Commissioner Rouleau’s final report, with findings and recommendations, by February 20, 2023—within one year of the emergency being revoked, as the Emergencies Act stipulates.

Stay tuned.

All the Parties with standing had the opportunity to provide written closing submissions on both the factual and policy phases of the Commission. You can find all the closing submissions here.

There are four types of national emergencies that can be declared under the Emergencies Act: a public welfare emergency, a public order emergency, an international emergency, or a war emergency. For more info, you can refer to this backgrounder. In this case, a public order emergency was declared.

On November 30, 2022, the POEC held a roundtable discussion on national security and public order emergencies. A transcript of the discussion can be found here.

A full transcript of CSIS director David Vigneault’s testimony on November 21, 2022 can be found here.

It should be noted here that while Chrystia Freeland is correct in saying that in 2021 the governing Liberals had campaigned on many of these policies and were elected (with a majority of seats--155 seats), they did not win the popular vote: Liberals (33.1%), Conservative (34.3%), Bloc Quebecois (7.6%), New Democrat (15.9%), Green (6.5%), People’s (1.6%), Independents (0.4%). So, it’s fair to question whether the Liberals really had what Freeland called a “fresh democratic mandate.”

Ewa Krajewska’s cross-examination of Tom Marazzo can be found on pages 197-199 of this November 2, 2022 transcript.

The federal government is currently working towards cybersecurity legislation—Bill C-26: An Act respecting cyber security, amending the Telecommunications Act and making consequential amendments to other Acts—which has undergone first reading and was tabled in the House of Commons on December 14, 2022, not long after the POEC concluded its hearings. The Bill currently sets out serious financial penalties for providers to ensure compliance, and gives government ministers the discretion to prohibit a telecom service provider from providing any service to a specified person in the name of security. The CCLA has been participating in publicizing the many serious and worrying flaws in the Bill, including that it opens the door to new surveillance obligations, allows for the termination of essential services, undermines privacy, and has no safeguards against abuse. They write: “Security vs freedom is a false dichotomy. Genuine security and safety require individuals to be safe from malicious actors and safe from unreasonable intrusion by the state, and while it’s a tough balance, it’s the balance democracy requires.” You can read more about the problems with Bill C-26 here and the Joint Letter of Concern.

The occupations were as serious as the attempted insurrection in Washington on January 6, 2021. The “trucker” protests felt different because they unfolded in slow motion and were cleared without violence.

Many Ottawans would say their health and safety, including their mental health, suffered during the occupation and still more would say they were afraid. For example, truck exhaust fumes were seeping into nearby apartments, which was obviously unhealthy. The occupiers were indistinguishable from goons; people were frightened to see them roaming their streets.

Ontario, like Alberta, was either unable to act or chose not to.

The protesters were not merely exercising the right to make their grievances known. To paraphrase PMJT, they didn’t just want to be heard; they wanted to be obeyed. They were extortionists. They were directly attacking the right and responsibility of democratically elected administrations to govern. Faced with this, two provincial governments effectively collapsed. That left the federal government alone with the problem and a blunt instrument with which to solve it. (You have to think some provincial politicians relished the idea of forcing a second Trudeau family member to suspend Canadian civil liberties.)

Democratic citizens endure countless infringements on their freedom because they recognize the rule of law as a net benefit. If they stop believing that, then we have a national security threat, a public order emergency that cannot be ignored.

Democracy looks like weakness to bullies and sometimes democrats need to remind them there’s an iron fist inside the velvet glove.