Do not try to save the whole world or do anything grandiose. Instead, create a clearing in the dense forest of your life and wait there patiently, until the song that is your life falls into your own cupped hands and you recognize and greet it. Only then will you know how to give yourself to this world so worthy of rescue.

— Martha Postlethwaite

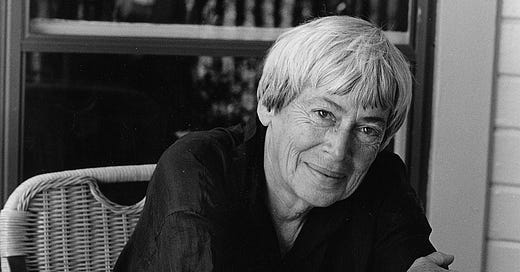

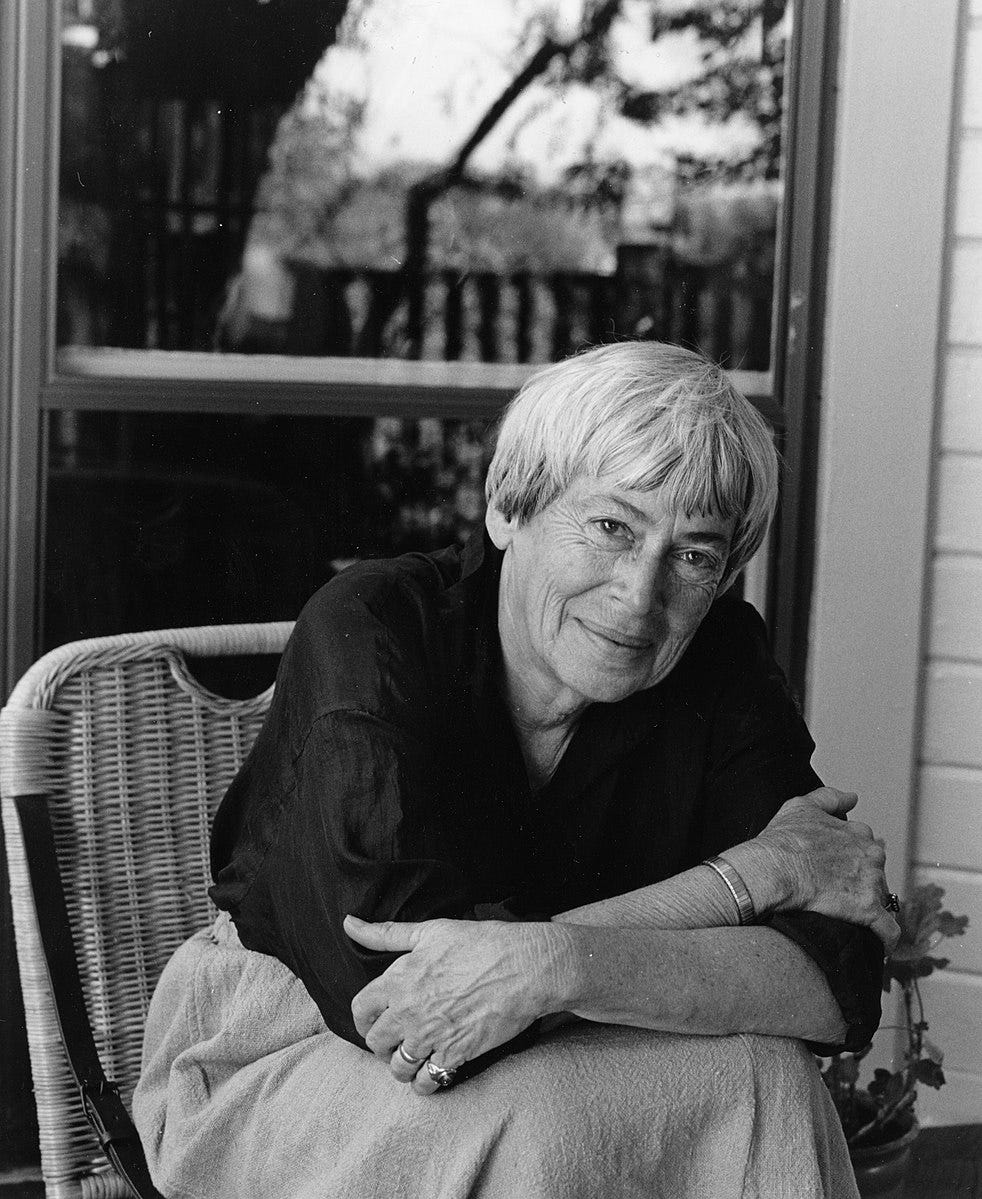

In 2014, four years before she died, Ursula K. Le Guin stood before an audience in Santa Cruz, California and gave one of the most stirring lectures I’ve ever heard. The Humanities Institute held a multi-day conference— “Anthropocene: Arts and Living on a Damaged Planet”—aimed at exploring whether it was even possible anymore for humans and other species to continue to inhabit the earth together, and Le Guin was the keynote speaker.

The author of more than 30 novels, including children’s books and poetry collections, was perhaps best known for her works of fantasy and science fiction. In Le Guin’s talk, it wasn’t surprising then that she positioned herself well into the future when humans—as she imagined us—would be in possession of so much more knowledge and understanding than what seems possible now. Reading from her own work from four decades earlier, she pointed squarely—in a kind way— at the grotesque arrogance of our species: how we think we know so much, and yet—about the things that truly matter—seem to know so little. For instance, given all the uncertainty that exists— that we know exists—how have we not made enough room to account for it?

In 1974 Le Guin published a book containing the short story, “The Author of Acacia Seeds and Other Extracts from the Journal of Therolinguistics.” Both the journal and the scientific field dedicated to the study of the language of nonhuman animals were fictional, but you can see the point Le Guin was making: of course nonhuman animals communicate, it is us who have not been able to understand it. And, if that is true, which it is, then why not plants? And, why must communication only be defined as the active kind?

Ursula K. Le Guin (Oct. 21, 1929 – Jan. 22, 2018) Photo credit: Marian Wood Kolisch (1995). Wikimedia Commons.

In Le Guin’s 1974 short story, she writes about the “kinetic sea writings of Penguin”:

Only when Professor Duby reminded us that penguins are birds, that they do not swim but fly in water, only then could the therolinguist begin to approach the sea literature of the penguin with understanding; only then could the miles of recordings already on film be restudied and, finally, appreciated. But the difficulty of translation is still with us.

Le Guin invited us to imagine the life of emperor penguins in the bleak, dark winters when nearly all they can hear is the “scream of the wind.”

In that black desolation a little band of poets crouches. They are starving; they will not eat for weeks. On the feet of each one, under the warm belly feathers, rests one large egg, thus preserved from the mortal touch of the ice. The poets cannot hear each other; they cannot see each other. They can only feel the other's warmth. That is their poetry, that is their art. Like all kinetic literatures, it is silent; unlike other kinetic literatures, it is all but immobile, ineffably subtle. The ruffling of a feather; the shifting of a wing; the touch, the faint, warm touch of the one beside you. In unutterable, miserable, black solitude, the affirmation.

In her talk, Le Guin reads from this story, bringing in two other fictional fields of science, namely phytolinguistics and geolinguistics.

Remember that so late as the mid-20th century most scientists and many artists didn’t believe that even dolphin would be comprehensible to the human brain—or worth comprehending! Let another century pass and we may seem equally laughable. ‘Do you realize,’ the phytolinguist will say to the aesthetic critic, ‘they couldn’t even read eggplant?’ And they will smile at our ignorance as they pick up their rucksacks and hike on up to read the newly deciphered lyrics of the lichen on the north face of Pike’s Peak. And with them, or after them, may there not come that even bolder adventurer, the first geolinguist – who, ignoring the delicate transient lyrics of the lichen will read beneath it the still less communicative, still more passive, wholly atemporal, cold, volcanic poetry of the rocks: each one a word spoken how long ago by the earth itself in the immense solitude, the immenser community, of space.

Cradling their young in a brood pouch, emperor penguins huddle to stay warm in the frigid Antarctic cold. Thousands of penguins participate in the densely packed huddle, that moves almost in waves, with continuous steps taken by the penguins, so that the huddle shifts and rotates to ensure that no penguin is ever left on the edge for too long. Screen grab from excerpt of Nature on PBS.

It reproduces as if by magic

In 2016 I had the fortunate occasion of meeting Frances Anderson for a piece I was writing about the boreal felt lichen, a species that had since 2002 been designated “endangered” by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC). Since monitoring began in 2007, scientists had noted a population decline based on the earlier recorded locations, but some new sites had also been identified. The decline is partly the result of clearcutting practices, but there are also other harmful anthropogenic factors including pollution, land development, and the application of aerial pesticides. According to its recovery strategy, the only known sites of the Atlantic population occur here in Nova Scotia.

In researching the piece, I reached out to Anderson, who co-authored a field guide on the common lichens of northeastern North America. She brought me to a now-protected forest about 30 minutes from my home, where for the first time I entered a microscopic world that was previously invisible to me.

While there was no boreal felt lichen in that particular forest, there was a huge diversity of other lichen species present. In one area where we were standing surrounded by red maple, white spruce, balsam fir, and tamarack – only four tree species – there was no less than 60 species of lichen. Anderson found 10 species on just one tree.

Anderson explained that at one time the forest’s moist micro-climate did support boreal felt lichen. At the base of a north-facing slope, it was once there amid the large red maples and old fir trees. When it was discovered, requirements were put in place on how close to the area forest cutting could happen, but as it turned out, the loggers came too close, beyond where they were supposed to go, and the boreal felt lichen disappeared, though their host trees were still standing.

It's not exactly clear what killed them, though it could have been the result of a slug invasion or it could have been that they were now much more exposed to “edge effects”—a change in the moisture, shade, and intensity of wind and weather because of the removal of the nearby, once protective forest. The loss of these necessary, hospitable conditions would have also made it much harder for them to reproduce.

As I’ve previously written:

Anderson spies a red maple with blue felt lichen, a species that is considered ‘vulnerable’ in Nova Scotia. It reproduces just like the boreal felt lichen does, as if by magic. “It has these red fruiting bodies that are producing fungal spores and for this lichen to reproduce itself the tiny fruiting bodies shoot out these spores that are microns big — just microns — and these things have to find the right algal partner,” she tells me. In the case of the blue felt lichen or the boreal felt lichen, the algal partner is a blue-green algae called a cyanobacterium. If the microscopic spore finds this particular microscopic partner it then has to find a place that’s hospitable to settle down and then those conditions have to remain fairly stable. “When you start taking out all the trees, these areas get more exposed to wind, so when the spores come out, they blow too far away and they don’t maintain their viability long enough,” she explains.

In other words, based on what we know about its life cycle—and much is still not completely understood—reproduction of the lichen depends on the chance encounter of a microscopic spore and a similarly small algal partner, and then the finding of the right tree and the right conditions.

But human activity is messing with these perfectly evolved conditions.

Boreal felt lichen is an endangered species, and the only known sites of the Atlantic population occur in Nova Scotia. Photo courtesy: Brad Toms/ Mersey Tobeatic Research Institute

Trees are ‘so much like us’

Back in 1969, American environmentalist Paul Shepard edited a book titled The Subversive Science, referring to the science of ecology — the one that looks at the relationships of organisms with one another and with the processes that link them to a place. But why did he consider the science of ecology subversive?

Shepard writes:

Ecology is sometimes characterized as the study of a natural ‘web of life’…But the image of a web is too meagre and simple for the reality. A web is flat and finished and has the mortal frailty of the individual spider. Although elastic, it has insufficient depth…Ecology as such cannot be studied, only organisms, earth, air, and sea can be studied. It is not a discipline: there is no body of thought and technique which frames [it]…. It must be therefore a scope or a way of seeing.

Shepard goes on to say that this “perspective” is “very old” and has been part of “philosophy and art for thousands of years.” Indeed, it was part of ancient cultures as well as the current lived and adapting wisdom of indigenous peoples.

If humans are linked to nature’s circuitous web of interconnections, as are all animal species, then knowing this would be subversive in that it would force us to rethink our place in the natural world.

As I’ve previously written, it was more than two decades ago that forest ecologist, Suzanne Simard and a team of researchers at the University of British Columbia had discovered that trees were connected to each other through an interconnected underground web of mycorrhizal fungi and it was through the transfer of carbon, nutrients, and water through this network that trees communicated. Simard also identified what she referred to as “mother” trees — the largest trees in the forest that acted as a “central hub for the vast below ground networks.” These mother trees “support young trees or seedlings by infecting them with fungi and ferrying them the nutrients they need to grow.” Her discoveries were published in the journal Nature in 1997 in an article called “The Wood Wide Web.”

Simard’s ground-breaking discoveries led to a raft of other studies and publications including Peter Wohlleben’s 2016 international best seller The Hidden Life of Trees, a book in which Simard also pens “Note from a Forest Scientist.” She writes:

We have learned that mother trees recognize and talk with their kin, shaping future generations… injured trees pass their legacies on to their neighbours, affecting gene regulation, defense chemistry, and resilience in the forest community. These discoveries have transformed our understanding of trees from competitive crusaders of the self to members of a connected, relating, communicating system.

Simard says “[trees] are so much like us, they live in societies… if we lose them we lose ourselves.” In 2021 Simard published her own book on the subject, Finding the Mother Tree: Discovering the Wisdom of the Forest.

Mother trees. Screen grab from book trailer for Suzanne Simard’s book, Finding the Mother Tree.

We belong to the world

In her talk, Le Guin suggested that our disregard for what we do not know allows us to place ourselves above all other life forms and to justify their objectification and therefore, destruction. She said, forests, animals, trees, and rivers are not natural resources. They are “kinfolk,” other beings.

“I’m trying to subjectify the universe because look at where objectifying it has gotten us,” she said.

Le Guin told her audience that what was required from us now—given what know as well as what we do not know—is that we “renew our awareness of belonging to the world.”

Le Guin:

How do we go about it? That awareness seems always to have involved knowing our kinship as animals with animals… and now both poets and scientists are extending our awareness of our relationship to creatures without nervous systems and to non-living beings – as fellowship as things with other things. Relationships with other things are complex and reciprocal… in this view humans appear as particularly lively, intense, aware nodes of relation in an infinite network of connections… infinite but locally fragile.

As I’ve written elsewhere, in many indigenous cultures, the only part of the world that was inanimate was what people themselves made. Everything else, the rocks, plants, animals, mountains, water, fire, and even places, were animate, alive—they were subjects, not objects.

In her highly acclaimed book Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants, Robin Wall Kimmerer weaves indigenous and scientific knowledge together to show the interdependence of people and the natural world. Kimmerer, a botanist and Anishinabekwe scientist, says indigenous cultures had rules governing what they took from the living world. While the details of these rules were specific to different cultures and ecosystems, they were fundamental principles of restraint that were common among those who lived close to the land to help shape their relationships with the natural world and “rein in our tendency to consume,” writes Kimmerer.

“The berries belonged to themselves,” Kimmerer said, of the strawberries growing in the field behind her house. They could not be owned, but they could be taken as a gift of sustenance from the earth.

Patch of wild strawberries. Courtesy Wiki commons.

I’ve spent the better part of 30 years trying to come to grips with our fraught relationship with the natural world, and I’ll be the first to admit that I feel a lot of anger, and sometimes despair about it. Anger is what often drives my writing: anger about the suffering humans are inflicting on species, including our own; over how money and greed have taken precedence over nurturing community and protecting our life support systems; at how governments of all stripes work in collusion with industry and have allowed the liquidation of forests, along with the species that depend on them; how our provincial government has recently overseen the functional delisting of potentially thousands of hectares of significant wetlands—one of the most endangered ecosystems in the world— as well as turned its back on protecting natural coastlines from human folly, greed, and hubris; how governments lie to us, and how they are willing to ignore public will, and erode hard-won environmental policy on behalf of vested interests.

The list goes on an on.

Writing about these things is a way for me to channel this anger in hopefully a productive way.

But I feel there needs to be more. How will I, as Le Guin advises, contribute to the renewal of awareness that we belong to the natural world? I’ve been thinking about this for some time and have decided that I will be introducing an occasional series here called, “Lichen Songs”—drawing on Le Guin’s phrase, “the delicate transient lyrics of the lichen.” Surely if there are lyrics there must also be song.

I hope to highlight some of these hidden connections and communications, and the astonishing beauty surrounding us.

The way I imagine it, the series could be described as nature writing, but I’m hesitant at this point to define what is yet to come. I’m not sure how it will fall into my cupped hands, or how it will be delivered to yours. But rest assured, it is coming.

As I have been doing since I began this Substack offering in January 2022, I’ll be taking a break from actively writing through the summer months – unplugging to recharge, so to speak. However, I will be doing some research for an upcoming collaboration—but more on that later on. As well, I am always thinking about and researching future stories. I already have a few ideas lined up and will be thinking more about them over the coming weeks.

Last week five boxes of clay finally arrived at my door, and I’m looking forward to being in my studio throwing pots, and making a sculpture or two. I might even post a pic or two of what comes of it.

Thank you for sticking with me and the Quaking Swamp Journal, and for supporting my writing in whatever way you can. If you have not yet taken out a paid subscription, and are able to do so, please consider it. I’m still committed to keeping all of my work out from behind a paywall. So, if you’re reading and enjoying my work, please subscribe and share.

I wish you all a wonderful summer.

It sounds like you are finding your way forward - what to do that will be helpful and meaningful to nature, humans, the planet. I have given this some thought. I seem to have moved into a new space. Only the rare op-ed or angry letter to the government, or social media rant. For me, what seems most useful is just sharing what I know and/or discover about the natural world around me - like the moths. I always come back to the thought that people will protect what they love -- and they can't love what they don't know about. Anyhow, that's really where my mind has been at for years, but for the distraction and anger caused by the destruction that I see in many places.

Anyhow, I hope you have a good break and spin some clay, or sculpt. It's a good time of year to rest, be creative and to explore new directions. I'm doing some painting, a lot of bird watching just on my own property - watching the birds raising their young - watching insects and photographing moths at night. Here's to a good long summer. :)

Really excellent article, Linda. Thank you for this.

Just wondering how you feel about sharing it on social media (ie, Facebook) -- obviously with credit and suggesting people subscribe to the Quaking Swamp Journal to read more of your work.