“If we surrendered to earth’s intelligence we could rise up rooted, like trees.”

— Rainer Maria Rilke

Detail from Mackerel (oil painting) by Paul Martin

The chilled water of September brings a flurry of activity to the bay near my home on the South Shore of Nova Scotia. Along the craggy shoreline of my morning walk a school of fish advance, like a dark cloud in a sea of green. Its contours shift seamlessly, mysteriously even, as each individual moves somehow in tandem with the next like one body, one organism. The school passes in front of me three times and each time I am enthralled by the ripples created by their underwater manoeuvring and the synchronous glints of light. Unsure of what kind of fish they are, I inquire later at the local fish store. “What you saw was a fall run of mackerel, dear,” confirmed the fellow behind the counter. “Soon they’ll be heading out to sea, when the water here gets colder. October, maybe.”

While in the shop, I spy some of the caught mackerel for sale and stand there mesmerized by the dazzling colours and patterns. The upper part of the nine-inch bodies a steely blue-green with dark wavy bands running through them, and the lower half an almost glowing silvery-white. Apparently, and only when the fish is alive, the colours are iridescent, like butterfly wings and seashells.

Once back home, I couldn’t help but wonder what a fall run of mackerel would have looked like in St. Margarets Bay 400 years ago when the Mi’kmaq summered in this place, the Aspotogan Peninsula—a corruption of their word Ashmutogun—which means “where the seals go in and out.” Back then, the nomadic Mi’kmaq— who had for thousands of years (estimates range from 5,000–13,000 years) lived in what we now know as Canada’s Maritime provinces, parts of eastern Quebec, and northern Maine—carried out a subsistence lifestyle of settling along the coasts in summer and moving inland to the lakes in winter. For thousands of years the plenitude of the land and seas sustained them. We’ve all heard the descriptions of how the fish were so plentiful they could be scooped up in buckets, so thick you could hardly row a boat through them.

With the image of this pre-contact abundance conjured in my mind, the marvel I experienced just a few hours earlier is suddenly shattered. Over the last four centuries everything has changed. What I witnessed was nothing in comparison to what once was—we have systematically and ruthlessly emptied the ocean of fish. But as Daniel Pauly has pointed out, we hardly even notice it. In a phenomenon he calls “shifting baseline syndrome,” the University of British Columbia fisheries scientist describes how each generation of fisheries scientists (but it applies to the general public as well) “accepts as a baseline the stock size and species composition that occurred at the beginning of their careers, and uses this to evaluate changes.” What is frightening about this is that it means we measure the changes from the recent past and in so doing we accommodate for the creeping loss. The truth is, Pauly’s warnings about fish could just as easily be applied to forests, wetlands, ice sheets, terrestrial life—to the entire living world, really. We have systematically taken from the earth and damaged the ecosystems that we all depend on, at times irreversibly. 1

The shoreline on Nova Scotia’s Aspotogan Peninsula —a corruption of the Mi’kmaq word Ashmutogun—which means “where the seals go in and out.” Photo: Linda Pannozzo

Worldviews Collide

In the 1630s, Nicolas Denys, a French aristocrat and a lieutenant on an expedition to the New World, founded various settlements in the area we now refer to as the Maritimes. Considered to be one of the first naturalists to write about Nova Scotia and its surrounds, Denys provided some of the earliest written accounts of the natural abundance found here four hundred years ago. In his 1672 two-volume book, he described great quantities of fishes in places that today are nearly barren by comparison—an “inexhaustible manna” of cod, and salmon so plentiful that the noise of them entering the river at night, “falling upon the water after having thrown or darted themselves into the air,” made it impossible to sleep. He also noted that the smallest of these fish was three feet long and that the mackerel—unlike the ones I spied in the local fish store—were “of monstrous bigness.”2

In his book The Native People of Acadia, Denys described the Mi’kmaq as being rooted in the stories passed from one generation to the next “so that it seemed that they had direct knowledge ... of matters of ancient law.” Denys also made a significant observation when he noted that they only kill animals in proportion to what they needed. “When they were tired of eating one sort, they killed some of another; if they wished no longer to eat meat, they caught some fish. They never made any point of amassing skins of moose, beaver, otter, or others, but only as they needed them for their purposes.”3

In 1995, nearly 220 years after Denys penned his descriptions, the late Daniel Paul—a Mi’kmaq himself and at the time the founding executive director of the Confederacy of Mainland Mi’kmaq—added an Afterword to his own book, We Were Not the Savages: A Mi’kmaq Perspective on the Collision between European and Native American Civilizations. In it he took issue with some of Denys’s observations, particularly those referring to the stories and descriptions of other Europeans of the colonial period, including missionaries, recorders, lawyers, and ship captains.

“When analyzing and evaluating the information left behind by these individuals one must always keep in mind that they are writing from an European perspective. The European belief of the time, which was that if one is not Christian then he is not civilized, played a large part in how they committed their thoughts to paper,” wrote Paul.

In other words, what is most valuable about Denys’s descriptions, inaccurate as they may be about Mi’kmaq ways, is that they shed some light on the perspective and worldview of the first Europeans to arrive in what is now Canada.

In his seminal book, Paul explained that prior to European settlement, the Mi’kmaq lived in “countries that had developed a culture founded upon three principles: the supremacy of the Great Spirit, respect for Mother Earth and people power,” and as a result they lived in a “harmonious, healthy, prosperous and peaceful social environment.” The Great Spirit, he says, was personified in all things—rivers, trees, spouses, children, friends. “Nature, as was the case with most American civilizations, supported Mi’kmaq religious beliefs.” In other words, the values of the Mi’kmaq (indeed all Indigenous peoples in Canada) and the Europeans stood in sharp contrast and “in most cases were completely opposite.” Europeans, both English and French, brought “a well-developed expertise in how to pollute and destroy Mother Nature. Their uncontrolled industrial development would eventually turn whole parts of the Americas into wastelands.”4

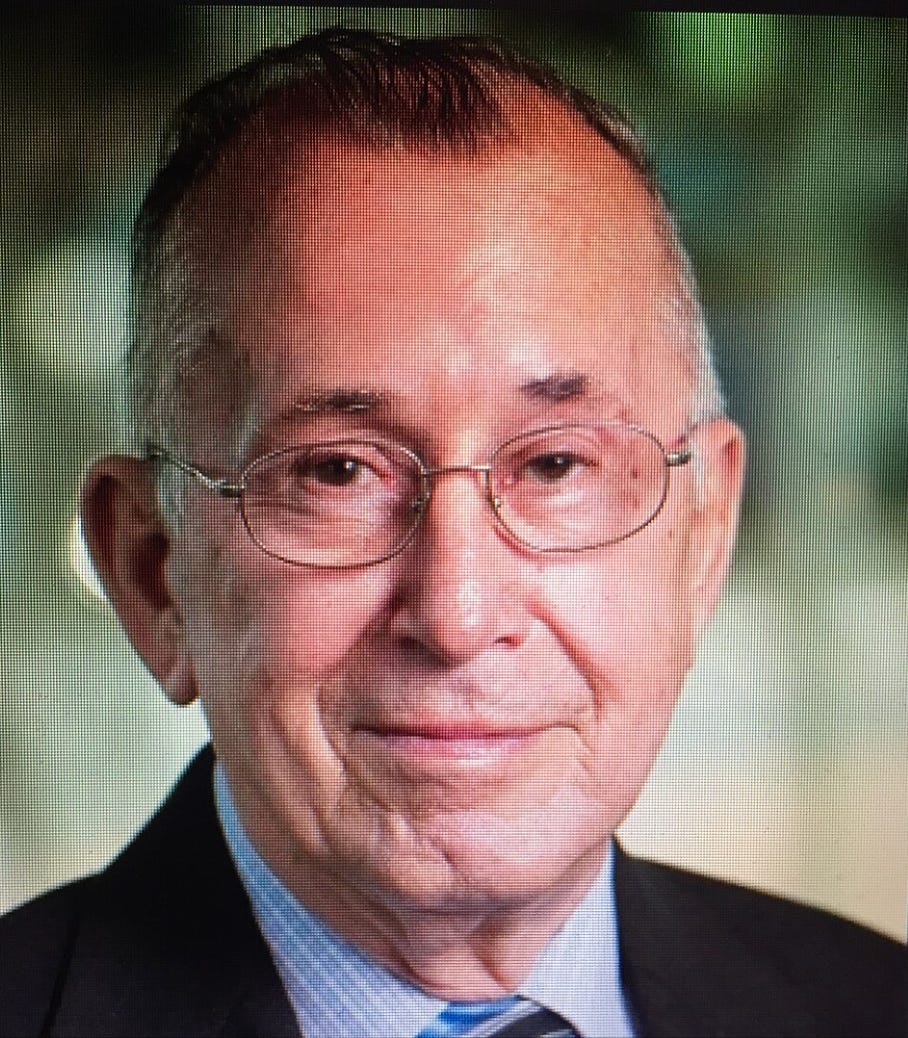

Daniel Paul (December 5, 1938 - June 27, 2023)

In her highly acclaimed book, Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants, Robin Wall Kimmerer weaves indigenous and scientific knowledge together to show the interdependence of people and the natural world. Kimmerer, a botanist and Anishinabekwe scientist, says indigenous cultures had rules governing what they took from the living world. While the details of these rules were specific to different cultures and ecosystems, there were fundamental principles of restraint that were common among those who lived close to the land. She refers to “the indigenous canon of principles” as the “Honourable Harvest,” which she says shaped their relationships with the natural world and helped “rein in our tendency to consume.”5

Thinkers in the relatively new field of environmental history, argue that there were practical reasons for indigenous people to be grounded in ecological knowledge. For instance, eco-feminist philosopher and science historian Carolyn Merchant, author of The Death of Nature, argues that for most of human history, nature has had power over humans. “People accepted fate while propitiating nature with gifts, sacrifices, and prayer.”6

This discussion is not intended to romanticize indigenous societies, because that kind of oversimplification can also be a destructive force. Kimmerer points out that the rules and cautionary tales were designed to discourage the taking of too much. The fact that these principles and stories were needed implies a human tendency to do otherwise—a dark side that needs to be recognized and addressed. She says that ignoring these tendencies could be catastrophic, and gives an example of how overhunting by indigenous hunters during the fur trade brought famine to the villages.

Archeological and historical research conducted since 1950 has shown that any notion of a time in history when humans were in “eternal equilibrium with equally stable natural systems are almost surely golden-age myths.” In other words, there was no “pristine” wilderness prior to European contact. The indigenous people throughout the Americas, to a greater or lesser extent depending on their population, changed and shaped the landscapes in which they lived.7

In Canadian Environmental History, University of Wisconsin professor William Denevan explains that in 1492, when Christopher Columbus reached the New World, the indigenous populations were “substantial” and estimated at roughly between forty-three and sixty-five million, with roughly forty-seven million occupying what we know today as Central and South America, three million in the Caribbean islands and nearly four million in North America. Archeological evidence shows that the landscape of 1492 was an altered one—forests had changed, grasslands expanded, agricultural fields created, and in the most populated areas, houses, towns, roads, and even erosion. This altered landscape largely vanished by the mid- 18th century as a result of what has been referred to as genocide. The onslaught of massacres as well as Old World diseases, for which the indigenous peoples had no immunity, ravaged the populations to such an extent that in the first century after contact in the most populous regions nearly 90 percent of the population was wiped out, and in North America the population dropped by 74 percent, leaving only one million indigenous people in 1800. This dramatic change in population size resulted in a landscape reversal, so that by 1750 it was more “pristine” than it had been 250 years earlier. “Paradoxical as it may seem, there was undoubtedly much more ‘forest primeval’ in 1850 than in 1650,” writes Denevan.8

According to Clive Ponting in his book A New Green History of the World: The Environment and the Collapse of Great Civilizations, to a large extent the “driving force” behind human manipulation of the environment has been size. As human populations have steadily increased, so too has the need to provide food, shelter, and clothing. But the next point he makes is key: “The way in which human beings have thought about the world around them has been important in legitimizing their treatment of it.” The way of thinking about the living world (our worldview) that has become dominant in the last few centuries, says Ponting, originated in Europe.9

By the time the Europeans discovered the Americas, Europe was already steeped in a lethal mix of science, technology, capitalism, and religion. Indeed, Merchant says that by the 17th century these “interlinked” forces allowed for “great power over nature” to be achieved. And without any of the stories or guiding principles that Kimmerer writes about—calling for restraint, gratitude, and reciprocity—the results were nothing short of ruinous.

Carter’s Beach, Nova Scotia. Photo: Linda Pannozzo

From Cosmos to World Machine

In Europe, from the 5th to the 15th centuries, the medieval worldview was one of reverence and mysticism, of an “organic, living, and spiritual universe.” According to renowned physicist and author Fritjof Capra, “All of nature’s parts had an innate purpose and contributed to the harmonious functioning of the whole, and objects moved naturally toward their proper places in the universe.” This European understanding of the natural world as having goals and purpose is not so different from the indigenous understanding of nature. Kimmerer says that for her ancestors the only part of the world that was inanimate was what people themselves made. Everything else, the rocks, plants, animals, mountains, water, fire, and even places, were animate, alive—they were subjects not objects.

“The berries belonged to themselves,” Kimmerer said, of the strawberries growing in the field behind her house. They could not be owned, but they could be taken as a gift of sustenance from the earth.10

This indigenous view is not so different from another element of the medieval worldview, “animism,” which holds that non-human entities (including what we’d think of today as inanimate objects) possess a force or spiritual essence, that there is no separation between the physical and spiritual or between humans and the natural world—and that God is in everything.

But by the 16th and 17th centuries the medieval worldview had changed radically and was replaced by one that viewed nature as a machine. According to Capra, this “world machine” became the dominant metaphor of the modern era, brought about in part by the revival of old Greek discoveries and thought. As well, new discoveries in physics, astronomy, and mathematics associated with now-familiar names—Nicolaus Copernicus, Galileo Galilei, René Descartes, Francis Bacon, and Isaac Newton—became known as the Scientific Revolution. Galileo’s view that the laws of nature were mathematical, Descartes’s linear and analytical thinking and subject-object dual- ism, Bacon’s scientific method, and Newton’s mechanics succeeded in “breaking up complex phenomena into pieces to understand the behaviour of the whole from the properties of its parts,” writes Capra. In essence, the material universe, including all living organisms, could be reduced to and understood by its smallest parts (think Einstein’s cracking open of the atom).11

Quality, which includes our experience of the world, was essentially “banned” from science, and all that mattered were those phenomena that could be measured and quantified—objectivity rather than subjectivity ruled the day. Along with quality and experience went the interconnections, the relationships between things, since interconnections are not measurable and are only knowable through subjective experience or perceptions. Kimmerer observes that Western science is premised on subject–object duality—the idea that everything in the world must fall into one of these two categories. Trained in the science of botany, she says she was taught that plants are objects not subjects, that humans exist apart from the living world, and that everything can be reduced to its working parts. Western reductionist science “as a way of knowing” is “too narrow” and not able to address “what lies beyond our grasp,” she says, like questions about beauty and the recurrence of patterns in nature. Because science is so “rigorous in separating the observer from the observed, and the observed from the observer,” it has difficulty addressing questions of beauty because it would “violate the division necessary for objectivity.”12

Peter Harrison is a historian, professor, and director of the Centre of the History of European Discourses at the University of Queensland in Australia and is best known for his influential writings on religion and the origins of modern science. He says that the revolutionary views of many of the key figures in the new science were rooted in their own religious assumptions. By the 17th century, the prevailing “pagan” science of the medieval times that viewed nature as somewhat autonomous, self-organizing, and governed by its own properties was replaced by the view that there were laws governing nature. “Natural objects were stripped of inherent properties and God assumed direct control of their interactions,” writes Harrison. “In the same way that [God] had instituted moral rules, he was now thought to enact laws which governed the natural world.”13

The crucial point here is that the prevailing worldview in Europe shifted from one where “the world was animated”—where God was immanent (present in the world)—to one where God becomes transcendent (removed from the world). The scientific revolution and discoveries of universal laws of nature—heliocentrism and the sun’s central position, the laws governing planetary motion, and laws of gravity and motion—suggested to these early scientists that there must be an all-powerful designer. God, like the proverbial watchmaker, designs and constructs the earth, including the laws that govern it, and then sets it in motion—but God is no longer thought to actively intervene in the world. This view contributed to a shift from a spiritual world to a mechanical one.

“The world had to be ‘disenchanted’ in order to be dominated.”14

Tree-like patterns in the sand. Photo: Linda Pannozzo

A Lethal Mix

According to Steven Shapin, a professor of the history of science at Harvard University, in order to understand the appeal of the “nature as machine” metaphor in the new science one needs to appreciate the power relations of early modern European society. “Patterns of living, producing, and political ordering were undergoing massive changes as feudalism gave way to early capitalism,” he writes. It would be an economic transformation that would ultimately change the course of history.15

Starting in the 15th century, an early form of capitalism emerged called mercantilism, which called for the accumulation of wealth as a means to power. In her book Caliban and the Witch, feminist scholar Silvia Federici writes that land, and the resources on that land, were commonly owned (often referred to as “the commons”), but with the development of capitalism came the idea of private ownership. Privatization was a way to achieve—or, more likely, increase—wealth and power, but privatizing land that had always been held in common was not an easy, or bloodless, task. It took different forms—evictions, increases in rent, increases in land taxes, the destruction of ways of life—all aimed at removing people from the land. “Throughout Europe vast communalistic social movements and rebellions against feudalism had offered the promise of a new egalitarian society built on social equality and cooperation,” writes Federici, and capitalism was the response of the powerful to this.16

Federici argues that the development of capitalism had “a single logic” governing it and that there was continuity between what was happening in Europe and what happened in the New World. “In both cases we have the forcible removal of entire communities for their land, large-scale impoverishment, and the launching of 'Christianizing' campaigns destroying people’s autonomy and communal relations.”17

European explorers who encountered the New World as far back as a thousand years ago had been spreading the news of a land of riches and plenty. That North America could provide a steady supply of raw materials was no secret, and by the mid-1500s, the English and French began building forts and trading posts “to enhance the prospects of satisfying their insatiable appetites for acquisitions” and “power,” wrote Daniel Paul. This “lust” possessed by Europeans was not a trait instilled in most Amerindian peoples, he said. “It was this inability to conceptualize societal greed and the notion of personal ownership of Mother Earth that prevented the Mi’kmaq from appreciating the motives behind French and English hostilities in Acadia.” Paul said that well into the 19th century many Mi’kmaq still believed land could not be bought or sold.18

Kimmerer says that to her people, land was “identity, the connection to our ancestors, the home of our nonhuman kinfolk, our pharmacy, our library, the source of all that sustained us ... land held in common gave people strength.” She says that because it was seen as a gift, land could not be bought or sold. These unwritten legal traditions that sovereign indigenous nations practised for thousands of years were soon made null and void by the European worldview embodied in the English structure of law. These laws facilitated the exploitation of new lands and legitimized colonization as a form of discovery, and, once land was colonized, gave the colonizer the right to use and abuse nature as a resource. Any cultures that stood in the way of this were either subjugated or eliminated.19

In his book Red Skin, White Masks, University of British Columbia professor and member of the Yellowknives Dene First Nation Glen Coulthard writes that “state power” in Canada sought to destroy indigenous culture and marginalize his people, “with the ultimate goal being our elimination, if not physically, then as cultural, political, and legal peoples distinguishable from the rest of Canadian society.” He says policies that were put in place were “unapologetically assimilationist” and that they were “aimed at explicitly undercutting Indigenous political economies and relations to and with the land.”

Coulthard quotes the commissioner of Indian Affairs in 1890, who at the time was involved in subdividing the reserves—paltry pieces of land onto which indigenous communities were forcibly relocated—when he said:

The policy of destroying the tribal communist system is assailed in every possible way and every effort [has been] made to implant a spirit of individual responsibility instead.20

Coulthard and others observe that the colonial relationship between the state and indigenous people is not just a thing of the past, but continues in current practices and structures, which are still rooted in exploitation of people and land, and in an economic system based on infinite growth.

When will we start incorporating the ancient as well as the current lived and adapting wisdom of indigenous peoples into the worldview that still dominates?

I’ve been told that the ancestors of the Mi’kmaq were taught and practiced the concept of Netukulimk, which means “to respect the land, not take more than you need, and leave something for the future.”

It’s a lesson we would all do well to take a crash course in.

[This piece was adapted from the first chapter in my 2016 book, About Canada: The Environment, “Our Romance with Reductionism.”]

D. Pauly, 1995, “Anecdotes and the Shifting Baseline Syndrome of Fisheries,” Trends in Ecology and Evolution 10 (10), p. 430.

N. Denys, 1908 [1672], Description and Natural History of the Coasts of North America (Acadia), translated and edited by William F. Ganong, Toronto: The Champlain Society, cod, p. 257; noise of salmon, p. 199; size of salmon, p. 166; size of mackerel, p. 184.

Denys, Description and Natural History, p. 65.

D.N. Paul, 2006, We Were Not the Savages: Collision between European and Native American Civilizations, Halifax: Fernwood Publishing: pp. 7, 10, 14, 57.

Robin Wall Kimmerer, 2013, Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants, Milkweed Publishing, p. 180.

C. Merchant, 1980, The Death of Nature: Women, Ecology, and the Scientific Revolution, Harper & Row, p. 61.

W. Cronon, 2006, “The Uses of Environmental History,” in D.F. Duke (ed.), Canadian Environmental History, Canadian Scholars’ Press, p. 33.

W. M. Denevan, 2006, “The Pristine Myth: The Landscape of the Americas in 1492,” in D.F. Duke (ed.) Canadian Environmental History, Canadian Scholars’ Press, pp. 93-95.

C. Ponting, 2007, A New Green History of the World: The Environment and the Collapse of Great Civilizations, Penguin Books, p. 141.

F. Capra and U. Mattei, 2015, The Ecology of Law: Toward a Legal System in Tune with Nature and Community, Berret-Koehler Publishers, pp. 31, 37. Kimmerer, Braiding Sweetgrass, p. 25.

F. Capra, 1996, The Web of Life: A New Scientific Understanding of Living Systems, Anchor Books, p. 19.

Kimmerer, Braiding Sweetgrass, p. 42.

P. Harrison, 2012, “Christianity and the Rise of Western Science.” (online)

S. Federici, 2004, Caliban and the Witch: Women, the Body and Primitive Accumulation, Brooklyn: Autonomedia, p. 174.

S. Shapin, 1996, The Scientific Revolution, University of Chicago Press, p. 33.

Federici, Caliban and the Witch, p. 61.

Federici, Caliban and the Witch, p. 219.

Paul, We Were Not the Savages, pp. 49-50.

Kimmerer, Braiding Sweetgrass, p. 17.

G.S. Coulthard, 2014, Red Skin, White Masks: Rejecting the Colonial Politics of Recognition, University of Minnesota Press, pp. 3-4, 13.

This is a good one to read/reread today.

Great article that neatly summarizes a lot of history to show how we've arrived as a species at where we are today. I particularly appreciated the introduction of the concept and theory, "Shifting Baseline Syndrome." This connection to our collective amnesia and warning that we need to see a more complete picture of history (history of Nature in particular) is a key concept in today's Citizen Science movement, and the importance of "Two-Eyed Seeing."

Thanks for this, Linda!