Nothing to Fear: The Unvested Interests of Rosalie Bertell

Part 1: The years of living dangerously

On that day in October, 1979, when Rosalie Bertell was on her way home from delivering a talk at the Highland Hospital in Rochester, New York on the dangers of radiation, it’s highly unlikely she was thinking about the imminent danger she was in herself.

Bertell had become a thorn in the side of polluting and dangerous industries, and fought tirelessly for those she thought were most threatened by the effects of radiation: women and children, indigenous people who often lived in the vicinity of uranium mines and their toxic mill tailings, and those working in the mines and nuclear facilities. She was often referred to as the “anti-nuclear nun,”—a member initially of the Carmelite tradition and then later the Grey Nuns of the Sacred Heart—though this framing was often intended to be very dismissive, ignoring her exceptional knowledge, analytic capabilities, and qualifications including a doctorate in mathematics and biometrics, with application in medicine and a background as a cancer researcher specializing in the health effects of radiation.

In a biography about Bertell written by Mary-Louise Engels in 2005, Bertell herself retells the story of what happened on her way home from that talk in Rochester:

“I became conscious of a white car in the left lane. It was too close to my car, so I pulled back, and when I did, the driver manoeuvred into my lane directly in front of me and dropped a very heavy sharp object—metal, I think—out of the car, in line with my front left tire. I saw it coming, but I couldn’t move out of the way. I tried to straddle it, but it caught the inside of the tire and totally blew it. I think if I had hit it head on, it would have turned the car over.”

Bertell said she managed to get her car to the side of the road and while surveying the damage, another car, marked “sheriff,” pulled up behind her and the passenger got out, asked her some questions and said they would contact the Rochester police for her. The police never showed up and inquiries made later at the sheriff’s office by Bertell’s brother, who was a lawyer, revealed that the car that pulled up was not a sheriff’s car.

“The second car apparently was connected to the first one and had followed to see what had happened,” surmised Bertell. But this was as far as she was willing to speculate. Bertell had been threatened before in Rochester, but said she had no proof that the two incidents were in any way connected.

According to her biographer, one local newspaper headline read, “Who is trying to kill Sister Rosalie?”

A year earlier, in 1978, Bertell appeared on a popular evening news program in Rochester with executives from the Robert Emmett Ginna Nuclear Power Plant, where she argued that radiation policies were not only inadequate but dangerous. As she went out the door, Bertell recounted that one of the executives, “shook his fist at me and said, ‘We’ll get you! Stay out of here and never come back to Rochester. We don’t want you here.’” 1

According to her biography, Bertell’s criticisms of the nuclear facility came at a time when public scrutiny was the last thing it wanted, as it was among the 33-Westinghouse designed plants that the US Nuclear Regulatory Commission ordered temporarily shut down because of possible cracks in pipes. Additionally, around that time, there were three pending lawsuits charging Rochester Gas and Electric—the operator of the plant—with undue radiation exposure.

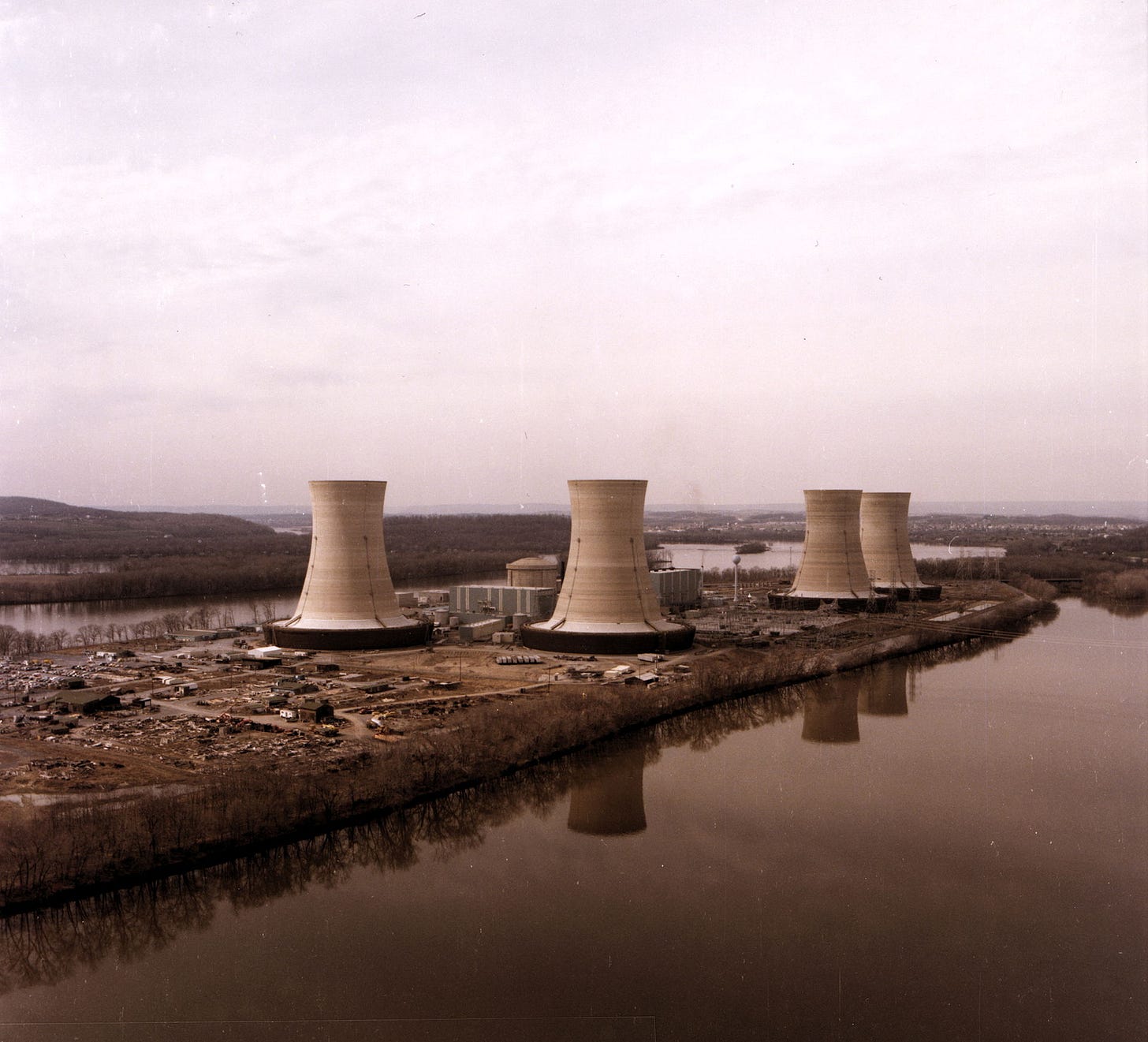

The partial meltdown of Three Mile Island nuclear plant in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania on March 28, 1979, was the most serious nuclear accident in US history. Wikimedia Commons (public domain)

The 1970s was a tumultuous time for the nuclear industry.

A few months before Bertell’s driving incident in Rochester, the nuclear industry was making international headlines, and not the good kind. In March of 1979, “a succession of mistakes, malfunctions, and misinterpretations” at the Three Mile Island Nuclear Generating Station near Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, brought the facility to within about a half hour of meltdown.2 While the accident was downplayed by government and regulators—they compared the near-by exposures to the radioactive effluent with the exposure from a single x-ray—a citizen’s health survey of 300 people living downwind reported injuries and deaths among pets and livestock.

In one incident, Bertell described how one commercial farmer lost 1,400 birds in one afternoon and when the health department was called, the dead birds were all taken away for study. “I saw the paper he received from the US Department of Agriculture,” she recounted. “It was a form list of known bird diseases, every one of which had been checked, ‘no.’ In the space at the bottom of the page, it said, ‘no known cause.’

“’Nuclear-fission accident’ was not on the government’s list,” exclaimed Bertell.3

Another pivotal event, also in 1979 was the jury verdict in a landmark legal battle for the family of Karen Silkwood, a lab technician at Kerr McGee’s Cimarron plutonium processing facility in Oklahoma. Five years earlier, Silkwood was exposed to radiation at the plant three times, and complained about how the company was taking short cuts, compromising quality control and endangering workers, many of whom didn’t have a clue about the danger radiation posed. On her way to a meeting with Steve Wodka, an official with the Oil Chemical and Atomic Workers International Union, and David Burnham, a reporter from the New York Times, she was killed in a car accident. It is alleged that Silkwood was in possession at the time of damning evidence against the company. Her story was the subject of the 1983 blockbuster film, Silkwood.

After her death, Silkwood’s family sued the company for physical and mental anguish related to radiation exposure at the plant. The civil case was in the courts for years. In the spring of 1979, Silkwood’s family was awarded $10.5 million (the amount they sued for) in the wrongful death civil suit, but when the company appealed the decision the appellant court cancelled the award. The Silkwood estate appealed that decision to the US Supreme Court and eventually settled out of court in 1986 for $1.38 million.4

Rosalie Bertell (April 4, 1929 – June 14, 2012); Photo: Right Livelihood

There was also a third noteworthy event around the time Bertell had her own brush with peril, one that involved the crux of the nuclear problem and also contributed to her long-standing distrust not only in nuclear technology, but in those who advocated for it.

In 1978, sensitive documents were released as part of a lawsuit brought by the State of Utah against the US government involving the excessive rate of leukaemia, cancers, infertility, and other health problems among the people in Utah who were exposed to fallout from bomb testing at the Nevada Test Site. The site was established in 1950 and a year later a B-50 bomber dropped the first nuclear device there.

According to a secret Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) memo unearthed by Carole Gallagher, author of the 1993 book, American Ground Zero: The Secret Nuclear War, the AEC had deliberately planned for fallout to blow over the St. George region of Utah in order to avoid Las Vegas and Los Angeles as the targeted communities were, according to the memo, "a low-use segment of the population."

But it wasn’t the first atomic bomb to be dropped on US soil. The world’s first nuclear explosion took place on July 16, 1945 when the US military detonated a plutonium bomb on the desert plains of the Almagordo bombing range in New Mexico, known as the Jornada del Muerto, or Day of the Dead.

Then, a few days later, on August 6th, the US dropped an atomic bomb on Hiroshima, Japan, and three days after that, another on Nagasaki.

In her 1985 book, No Immediate Danger: Prognosis for a Radioactive Earth, Bertell described the absolute horror of what took place in Hiroshima:

The fireball was 18,000 feet across, with a temperature of about 100 million degrees Fahrenheit at the centre. People who looked at the fireball were blinded. More than four square miles of this city of 130,000 people were completely destroyed. Houses collapsed from blast pressure or were destroyed by the fire which burned for two days. About 88,255 buildings… were destroyed. Some people near the centre of the explosion literally evaporated; others were turned into charred corpses. Survivors experienced burns which caused their skin to peel off immediately; some had skin hanging from the ends of their fingers. Those who lived to tell the story said that the victims looked like ghosts.

Then the US did it again in Nagasaki. Bertell said this time they dropped a bomb constructed of plutonium, while the Hiroshima bomb was made of uranium. There was a “deliberate plan to study the effects of the two different types of bombs,” she said. “The Nagasaki bomb exploded about 500m above the ground, near the University of Nagasaki Medical School.”5

Immediate fatalities in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, tallied years later, numbered 240,000, but this did not include the cancers, genetically damaged children, congenital malformations, children who die before age one, spontaneous abortions, and miscarriages caused by radioactive material. That all came later.

“The penetrating radiation had the power to invisibly destroy without the usual wounds so familiar to war,” Bertell recounted.

The US military detonated a plutonium bomb on July 16, 1945 on the desert plains of the Almagordo bombing range in New Mexico, known as the Jornada del Muerto, or Day of the Dead.

When Bertell was working on her 1985 book, she reported there had been 192 “announced” US above-ground nuclear bomb tests between 1946 and the 1963 above ground testing ban. By the time all nuclear testing was banned in 1996, there had been 928 nuclear detonations at the Nevada site.

Bertell wrote:

The decision was made to risk random deaths from cancer and other illnesses among the US and Canadian mid-west populations. These deaths were spread out over time (because of the long-lasting pollution of the land and the long time between individual exposure and development of a tumour or other health effects) and in space (since radioactive clouds passed over most of northern central and north-eastern USA and extended into Canada).

Not only did the nuclear explosions on US soil “risk random deaths,” as Bertell said, but soldiers participated, some of them voluntarily, in the nuclear blast manoeuvres, literally entering ground zero after each detonation, assured by their commanders that it would have “no lasting ill effects,” explained Bertell.

Bertell had championed the cases of those who were victims of atomic war exercises. She was a stalwart advocate for the rights and recognition of veterans who had been exposed to radiation in the cleanup at Hiroshima and Nagasaki, as well as those exposed to the nuclear weapons testing in Nevada. According to her biography, veterans’ claims were finally recognized by the landmark Radiation Exposed Veterans’ Compensation Act (1988) which began compensating veterans suffering from 15 types of cancer caused by radiation exposure. Two years later another Act compensated civilians who lived downwind of the Nevada Test Site.

Years later, Bertell also advocated for the people who suffered through the US nuclear testing in the Pacific Ocean, where they exploded 67 bombs between 1946 and 1958, including the first hydrogen bomb, sickeningly named “Bravo,” in 1952. The cumulative force of the nuclear bombs detonated on Bikini Atoll in the Marshall archipelago was equivalent to 7,000 times the bomb dropped on Hiroshima.

In Bertell’s biography, Engels writes:

The Bravo event…harmed not only the inhabitants, who were relocated to Rongelap and other nearby islands, but also many of the American servicemen who took part. Repeated massive testing caused lasting radiological contamination of all the test islands, and Bikini remains uninhabitable. High rates of thyroid cancer, birth defects, and Downs’ Syndrome have been observed.6

We will return to the subject of nuclear weapons testing later in this series, but it should be noted here that Bertell took it upon herself to visit the islands with a team of nurses and assess the health needs of the Rongelap people, eventually testifying before the US House of Representatives, advocating they receive compensation.

In the late 1980s, previously classified documents revealed that the Atomic Energy Commission “intentionally returned the Marshallese to island they knew were still toxic, in order to study their bodies’ reactions to life in a contaminated setting,” writes Engels.

Engels continues:

[Bertell] was haunted by the memory of the Rongelap women who bore grotesquely deformed babies after the nuclear testing. The women had hydatidiform moles—the people of the Marshall Islands called them ‘jellyfish babies.’ Says Rosalie: ‘It’s like a living mass that’s got some hair and some bones but no face and no limbs. It only lives as long as it’s connected to the umbilical cord. So the woman would carry it for seven or eight months… and she’d have this mole, just a blob of living material.’7

Abnormal births—much like what was described by Marshallese women—were also described by women in Utah who were downwind of the Nevada Test Site.

Downwind of the Nevada Test Site (black rectangle), Photo source.

In her 1985 book, Bertell reminds us that “nuclear generators were a necessary part of nuclear weapon production.”

Well before the technology was used to electrify people’s homes, fuel rods were being burned and plutonium was being extracted for bomb manufacturing. The term ‘atoms for peace,’ the title of a speech delivered by U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower to the UN General Assembly in December, 1953, basically meant that the by-product of this extraction process—the reactor steam—would be used for the commercial generation of electricity.

It was “an effort to make nuclear technology, with all its support industries, acceptable to society in general,” explained Bertell in her 1985 book.

The US Department of Energy called it “clean power forever.”

“It was an ingenious idea for winning broad-based co-operation, with everyone’s conscience feeling ‘clean’ and everyone’s intentions appearing idealist,” she wrote.

The first nuclear power plant supplying power to the grid was built in the Soviet Union in 1954. Two more followed in France and England in 1956, one in the US in 1957. By the mid-1980s there were more than 300 nuclear facilities in 25 countries.

While money was being poured into university and industry research for the civil applications of nuclear technology, “actual weapons production was also quietly increased,” wrote Bertell. “Most research had dual uses… a billion-dollar weapon industry was woven into the fibre of the US economy without most Americans being aware of it.”

Bertell said that not only was the truth about the atomic bomb—development, testing, and deployment— kept from the American people and their elected members of Congress, but the dangers of atomic radiation were kept secret too.

While many touted the benefits of nuclear technology, Bertell saw something else: “Public opinion was being manipulated by the control of information released by government officials,” she wrote.

“This tremendous power was to be managed by those who knew its secrets,” she wrote.

[Stay tuned for Part 2 of this series, in a couple week’s time. I’ll post as I write them. At this stage, I can’t say how many parts this series will entail, or exactly what the interval will be between them, but what I can say is, the series will take The Quaking Swamp Journal into the new year.]

Bertell quote about the verbal threats from Engels, Mary-Louise. 2005. Rosalie Bertell: Scientist, Eco-Feminist, Visionary. Women’s Press (Canadian Scholars’ Press Inc.), p. 85.

Engels, 2005, p. 87.

Bertell quotes taken from Engels, 2005, p. 88.

To this day the case remains shrouded in mystery. A 2024 KOKO 5 documentary on Silkwood’s death—50 years after it happened—raises more questions than it answers and does suggest that what happened to her car was not an accident and that her vehicle was hit from behind causing it to veer off the road, eventually hitting a concrete culvert. However, there is no definitive proof that this is the case.

The documentary also raises disturbing questions about what else might have been taking place at the Kerr-McGee plant. As the 2024 documentary lays out, there are serious questions around where the company’s missing plutonium – referred to as “material unaccounted for” (MUF)—was going. According to the KOKO 5 documentary, a secret court hearing took place between the judge who presided over the case and US intelligence officials (CIA and FBI) before a certain witness was scheduled to testify that plutonium taken from the Kerr-McGee facility was being smuggled into foreign countries to build nuclear bombs. KOCO 5’s investigation uncovered a memoir written by Justice Frank Theis, where he writes, “The court was informed that the information involved spies and counter-spies of the US and some foreign countries, and any disclosure outside the presence of the judge, his reporter, and our government officials would have international repercussions and endanger the lives of secret operatives and greatly damage our national security, or that of other cooperating nations and their secret operatives.” The details of the secret meeting are sealed.

Bertell quotes taken from Engels, 2005, pp. 136-137.

Engels, 2005, pp. 137-138.

Engles, 2005, p. 139.

This is an excellent series about Bertell. I'm fascinated. thank you

Thank you, Linda - such a timely reminder which one can only hope will weaken us to avoid repeating the terrible mistakes of the past.