“There is a vitality, a life force, an energy, a quickening that is translated through you into action, and because there is only one of you in all time, this expression is unique. And if you block it, it will never exist through any other medium and it will be lost. The world will not have it. It is not your business to determine how good it is nor how valuable nor how it compares with other expressions. It is your business to keep it yours clearly and directly, to keep the channel open.” – Martha Graham

Since mid-June I’ve had one foot in and one foot out of the “plugged-in” world. The foot that was out, was pushing down on the pedal of a potter’s wheel. I enjoy making things, and, like most of us, come from a long line of “makers.” Mine made ricotta, olive oil, wine, sausages, bread, pasta… and what they didn’t make, they might have bartered for. If something broke, they likely knew how to fix it. An economic system based on endless growth could not have lasted long in the frugal society that my mother grew up in. Life in pre-war Italy was a rugged one. As a child, my mother, who is turning 92 in a few weeks, was expected to bake bread, help raise chickens, turkeys and goats, and with her sister, walk miles to collect kindling for cooking. Clothes were sewn and mended, food was grown, and little if anything was wasted. My mother’s generation grew up in what we call now the Age of Consumerism—a period in which consumption patterns in Europe and North America shifted from fulfilling basic needs to fulfilling “wants.” It began around the time my mother was born and we’ve been on one long buying spree ever since.1

My mother, Maria Pannozzo, baking bread during a family visit to her childhood home in Campodimele, Italy. (1977) Photo: Linda Pannozzo

But while this shift from a subsistence to a money economy came with perks—like washing machines, vacuum cleaners, toasters, and radios—it also resulted in big changes to how people spent their time. Instead of producing items themselves and exchanging them for things other people produced, people began to shop for these mass-produced goods. The shift was driven by the economic system that emerged from the industrial revolution—an industrial version of capitalism—which was defined by private ownership, wage labour and the profit motive. This not only changed the structure of productive life, it forced people off the land into cities and waged labour. The nature and purpose of work was transformed. There was hardly time to make things anymore; what was needed and wanted was purchased. The significance of time also changed and became synonymous with profit and therefore needed to be controlled.

Simone Weil (Wikimedia Commons)

“To feel one is useful and even indispensable, are vital needs of the human soul”

The subject of work has occupied the writings and musings of many contemporary thinkers. Simone Weil, a moral and political philosopher who lived during the early part of the twentieth century, believed work was part of the rational soul of each person. According to Weil, work was ultimately spiritual because it was the way in which reality enters the body. In her 1949 book, The Need for Roots, Weil denounced the “cult of materialism” and said it led to a loss of spirit. Weil wrote that “to feel one is useful and even indispensable, are vital needs of the human soul.” She tied this need in with being “rooted.”

To be rooted is perhaps the most important and least recognized need of the human soul. It is one of the hardest to define. A human being has roots by virtue of his real, active and natural participation in the life of a community which preserves in living shape certain particular treasures of the past and certain particular expectations for the future.2

Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau also contemplated the value of work in human life. Emerson believed work was an organic extension of our selves. He said, "Let it be in your bones. In this way you will open the doors by which the affluence of heaven and earth shall stream into you." And Thoreau viewed work as an integral part of life but not as its sole purpose: "The really efficient labourer will not be found to crowd his day with work, but will saunter to his task surrounded by a wide halo of ease and leisure."3

In his compelling book Critique of Economic Reason, Andre Gorz viewed work as a "modern invention" which for the most part, "bears no relation to the tasks…which are indispensable for the maintenance and reproduction of our individual lives."4

Theodore Roszak echoed this view and pointed at the Industrial Revolution as the key turning point in the history of work. Work done in traditional societies was "thoroughly dignified and [an] intrinsically engaging use of life," wrote Roszak. Work after the Industrial Revolution became an "abstract commodity valued only as the means of earning the wages that purchased subsistence." In what became a classic, Person Planet: The Creative Disintegration of Industrial Society, Roszak wrote, “People are not asked to find themselves in their work, but to lose themselves in [it].”5

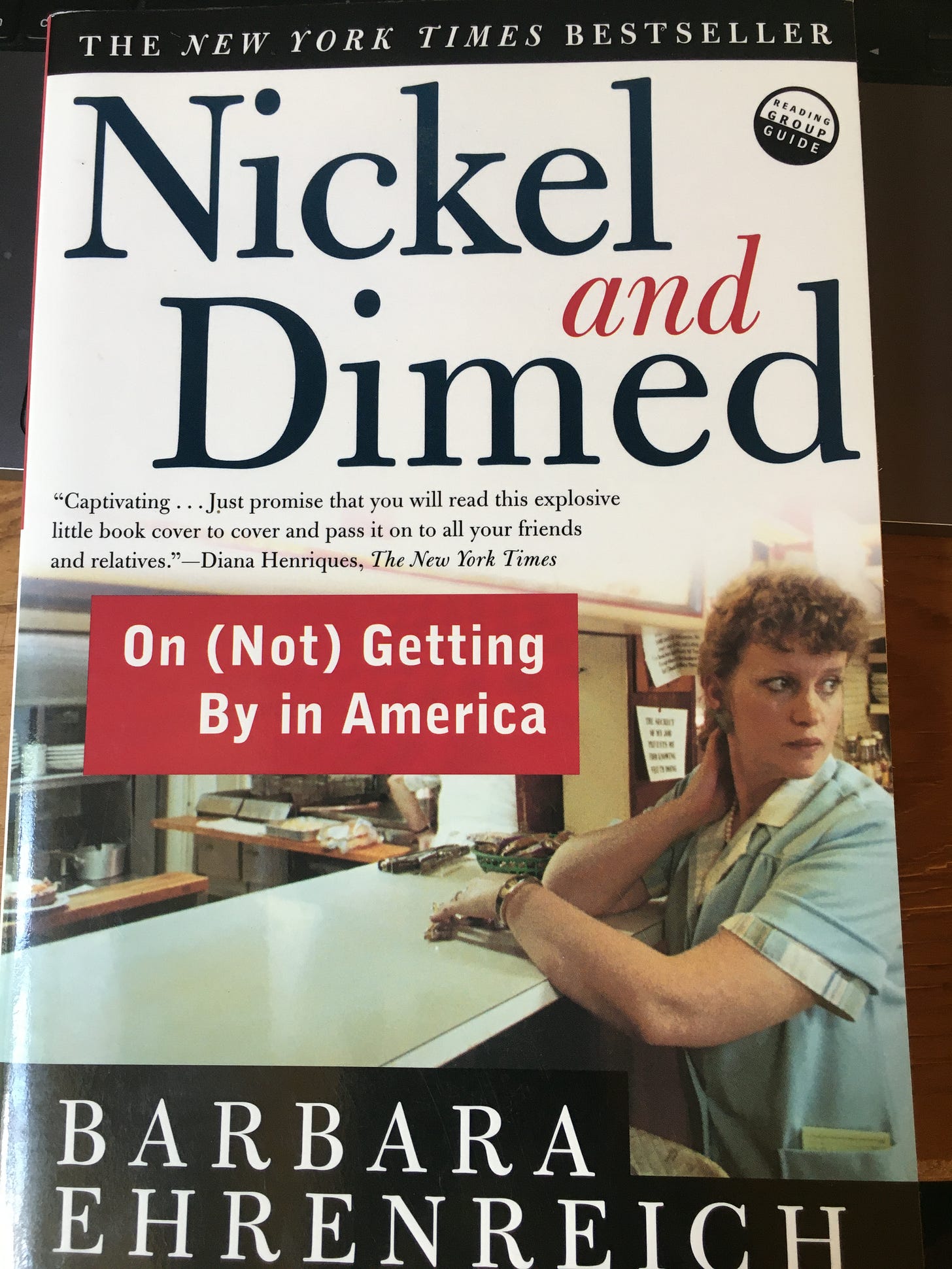

Cover of Nickel and Dimed: On (Not) Getting By in America, a modern classic by the late Barbara Ehrenreich (1941-2022).

Low-and-middle income workers figure heavily in the writing of author and essayist, Barbara Ehrenreich, who died on September 1st at the age of 81. Her most famous books were about work and she’s been described as “one of the greatest literary representatives of the working class.”

In what has become a modern classic, Nickle and Dimed: On (Not) Getting By in America, Ehrenreich went “under cover” in Florida, Maine and Minnesota taking on low-wage jobs as a waitress, hotel maid, house cleaner, nursing home aide, and Wal-Mart salesperson, and discovered that these lowest paid jobs were not only exhausting, they were often not enough to pay the bills. Many have to moonlight, or take on more than one job, just to get by. Ehrenreich found “there are no secret economies that nourish the poor; on the contrary, there are a host of special costs." She wrote:

The idea was to spend a month in each setting to see whether I could find a job and earn, in that time, the money to pay a second month’s rent. If I was paying rent by the week and ran out of money, I would simply declare the project at an end; no shelters or sleeping in cars for me… I was only visiting a world that others inhabit full-time, often for most of their lives… My aim here was… to see whether I could match income to expenses, as the truly poor attempt to do every day. Besides, I’ve had enough unchosen encounters with poverty in my life time to know it’s not a place you would want to visit for touristic purposes; it just smells too much like fear.6

In Nickle and Dimed, Ehrenreich said that what “surprised” and “offended” her the most about the low-wage workplace “was the extent to which one is required to surrender one’s basic civil rights and—what boils down to the same thing—self-respect.” She described a number of what she called “demeaning intrusions” including purse searches by management, drug testing, and pre-employment personality tests.

Ehrenreich didn’t see a conflict between being both a journalist and an activist. She said: “As a journalist, I search for the truth. But as a moral person, I am also obliged to do something about it.”

Barbara knew that the bright line that was enforced within the media between journalism and advocacy could, in truth, mask ideology. She knew that what counts as reporting neutrally can reinforce the status quo, recording only what is already there, in official language that has already been accepted and naturalized, or in acronyms and milquetoast phrases. It doesn’t capture what was once or could soon be a reality.7

After hearing about Ehrenreich’s death, I picked up Nickle and Dimed again. I read it years ago when I was working on a report about trends in work hours in Canada, with Nova Scotia as a case study. The report looked at quantitative trends in paid work hours, as well as the societal and health costs associated with the trends and found a disturbing rise in inequality, overtime work and “junk jobs.” Ehrenreich’s books, along with the pioneering work of Juliet Schor, Anders Hayden, Linda McQuaig, Heather Menzies, Simone Weil, Theodore Roszak, and Jim Stanford, helped shape my approach to tackling how the nature and duration of paid work had changed and how it was degrading our quality of life and sense of wellbeing.

While Ehrenreich was admired for her “clear eyed” writing style, or for, as New York Magazine put it, a relentless curiosity that led her to look “for the truth of a thing,” I realized upon re-reading her book that what I admire her most for is her empathy and ability to get into the lives of people and make us care about them.

In her book, Fear of Falling: The Inner Life of the Middle Class—written in the 1980s, when neoliberalism was just starting to take hold—Ehrenreich investigated the decline of the blue-collar working class in the U.S. and explained how, with its once strong unions and tradition of workplace defiance, became a "burden" to employers.

In 1955, when my parents first arrived in Canada—and about ten years before I was born—my father's first job was laying asphalt. He did that for about a year and then studied to be a welder. His first job as one was at Union Carbide, where he spent several months initiating the union effort. My mother tells me that when the union finally did get organized, everyone else benefited with a raise except the welders.

This kind of workplace defiance was commonplace when my parents first immigrated to Canada. But in her book, Ehrenreich described that what followed in the 1970s was a “brutal assault” by the corporate elite on not only the wages and living standards of the working class but on their very jobs. She said the “assault” was waged in a number of ways: first, manufacturing jobs were increasingly outsourced to lower paid third-world labour; capital was shifted from manufacturing to financial speculation; workers were reduced to "labour costs"; and full-time work was replaced by part-time work with no benefits.8 Between l979 and l984 alone, 11.5 million American workers lost their jobs due to plant shutdowns or relocations and according to Ehrenreich, 60% of these workers found new jobs, mostly within the service sector, which tend to be low paying, casual, and insecure.

She wrote that while many blue-collar workers lost their jobs and continued to do so, it was the decline in wages that contributed most to their declining living standards.

At the same time that many companies were shedding workers and cutting costs, they were also shifting many of the company's operations to other countries. In l927, for instance, at Henry Ford's River Rouge complex in Michigan, except for the mining of the ore, the production of cars took place from beginning to end in the same plant. In a 2002 article that appeared in Harper’s Magazine, Barry Lynn describes how "ships were unloading iron ore at one end of the complex while employees drove finished Model A's onto railroad cars at the other." But today, this kind of in-house production is a thing of the past. In its place, many companies have created a "vast network of outsourced production,"—the global assembly line.

[A] single semiconductor might be cut from a wafer in Taiwan, assembled in the Philippines, tested in China, fit into a subcomponent in Malaysia, plugged into a component in Brazil, and loaded with a program designed in India.9

So much of what we buy these days—whether it be clothing, food, or household items—is made in the global South by workers (including children) trapped in a cycle of exploitation.10 Photo: Linda Pannozzo

My summer of throwing pots is as much about getting into a zone of creativity as it is an act of resistance.

Like many people who grew up at some point during the Age of Consumerism, I feel a deep sense of loss at how removed we have become now from processes that are essential to our survival (food production, for instance). Making functional (and hopefully beautiful) items, like cups, bowls and candelabras is for me a way to rebel against the sterile, anti-nature, anti-human, outsourced economy. It’s my attempt (feeble as it may be) to reclaim a small part of the household economy. My summer of throwing pots is as much about getting into a zone of creativity as it is an act of resistance.

In his 2000 essay ‘The Total Economy,’ Wendell Berry writes:

The danger now is that those who are concerned will believe the solution to the ‘environmental crisis’ can be merely political – that the problems, being large, can be solved by large solutions generated by a few people to whom we will give our proxies to police the economic proxies that we have already given… The trouble with this is that a proper concern for nature and our use of nature must be practiced, not by our proxy-holders, but by ourselves.

Living intentionally within the confines of a finite system is no easy task, but I sense that there is a connection here to the notion of being able to engage in dignified and meaningful work–which should be a basic human right.

Earlier I noted that while I had one foot firmly planted on the pedal of my potter’s wheel, the other foot was still “plugged-in” elsewhere. That’s because all summer, when I wasn’t actively avoiding the news, I was engaged in reading it. When you take a step back, even if it’s only partial, you start noticing things. Whether it was about monkeypox or some new variant of COVID-19 or the potential for nuclear war, or the coming climate apocalypse, the news was written in a way to create fear and divisions instead of understanding; paralysis instead of action.

In a piece written for the Washington Post, Amanda Ripley writes:

The way forward is for journalists to adopt a new theory of change, abandoning the assumption that the way to avert catastrophe is to keep the public laser-focused on threats. And instead, decide that change comes when the public is informed about the bad news and the potential solutions to it... There is a way to communicate news — including very bad news — that leaves us better off as a result. A way to spark anger and action. Empathy alongside dignity. Hope alongside fear.

This is something Ehrenreich was really good at, and something all journalists can learn from.

Whether I’m pounding away at a lump of clay or at a keyboard, I want to be engaged in a way that’s both useful and meaningful. I want to “keep the channel open,” as dancer and choreographer, Martha Graham once said. This work doesn’t have to make me a living because at least it’s work I can live with.

For me, throwing pots is as much about getting into a zone of creativity as it is an act of resistance.

A Word about Subscriptions

I want to acknowledge the generosity of those of you who became “founding members” of the Quaking Swamp Journal, and those who decided to take out annual or monthly subscriptions. I am honoured by the financial support and the vote of confidence. I also want to thank those who took the time to write to me personally, leave voice messages and even send letters. My heart is full. As I’ve mentioned before, if you value what I’m offering, you can also support my work by sharing the articles with your family, friends and colleagues. All articles will continue to be outside the paywall and free for all to read.

There are a number of stories I’m working on and will publish them here in the coming weeks. Looking forward to hearing from you in the comment section or via email.

Your support of my writing—no matter how it manifests—means the world to me.

Section adapted from my 2016 book, About Canada: The Environment. (Fernwood Publishing)

Weil, Simone. 1949. The Need for Roots. Routledge Classics, London. p. 43.

Sinclair, Gabe. 2000. The Four-Hour Day. The Four-Hour Day Foundation, Inc. Baltimore, p. 124.

Gorz, Andre. 1988. Critique of Economic Reason. Verso. London, p. 13.

Roszak, Theodore. l979. Person Planet: The Creative Disintegration of Industrial Society. Anchor Press. New York. pp. 213-215.

Ehrenreich, Barbara. 2001. Nickel and Dimed: On (Not) Getting By in America. Henry Holt and Company. New York. pp. 5-6.

Ehrenreich, Barbara. 1989. Fear of Falling. The Inner Life of the Middle Class. Pantheon Books. New York. pp. 206-208.

Lynn, Barry. 2002. “Unmade in America. The True Cost of a Global Assembly Line.” Harpers Magazine. Vol. 304, no. 1825. New York. pp. 33-41.

By global South, I mean spaces and peoples negatively impacted by globalization, which includes subjugated peoples and poorer regions within wealthier countries.

Excellent analysis of the incredible disconnect that modern neoliberalism has created in people.

And it's not just what it does to the poor working class people. David Graeber wrote a book Bullshit Jobs, A Theory. From the review of his book by Mary Tracey,

''In 2013 David Graeber told the world what many of us secretly believed but were too afraid to admit out loud: many modern jobs appear to be bullshit because they are, in fact, bullshit. Graeber’s argument is that automation has already happened, but instead of freeing us from the tyranny of the 40 hour work week, we have invented a whole crop of pointless occupations that are at best unnecessary and at worst pernicious. What is a Bullshit Job? A job you secretly believe to be pointless and meaningless. What could be the point of pointless jobs? This is what Graeber seeks to find out with this book. The point of pointless jobs is that they are politically useful.

Here is the core argument of the book: we are no longer living under “Capitalism“. We are living under a system Graeber calls “Managerial Feudalism”, where most of the money comes from either “rents” or “debt”, precisely like in the days of feudalism proper. In other words, the “FIRE” sector: finance, insurance, real estate.

We are used to thinking about the economy as “production”, that is, making things. But under this “Managerial Feudalism”, the money flows to the elites, the owners, regardless of what workers do. And so “doing” becomes less important.

What, then, to do with all that money, but buy a whole cohort of people who will be kept in comfort and security and who, in exchange, will swear loyalty to the system, to feudalism; people whose wealth and status prove, by definition, that the system “works”, that some get to do very nicely indeed.

To put it in simple terms: the economy is no longer run by the “making of things” but by the “stealing of money”, and so large chunks of people are employed in the stealing of said money (jobs) and in the pretending that they aren’t (bullshit)."

https://davidgraeber.org/david-graeber-i-would-like-this-book-to-be-an-arrow-aimed-at-the-heart-of-our-civilisation/

And your pottery is beautiful and useful!! Great article!