Remote Control

Part 2: The pandemic ushered in a surge of surveillance under the guise of safety, but we’ve never been more exposed.

It would afford the “most perfect view of every cell.”

Or at least this is how Jeremy Bentham imagined it. The panopticon—Greek for “all seeing”—was Bentham’s idea of the model prison. Prisoners’ cells would be arranged in a circular fashion around a central “inspection house,” where the guards could see into all the cells. But through a series of “blinds and other contrivances,” the prisoners could not see the guards. Bentham, best known as the founder of modern utilitarianism, was a renowned English philosopher who spent a good decade trying to convince the British government that this scenario—being watched continuously, or at least thinking you were—would improve inmates’ behaviour.1

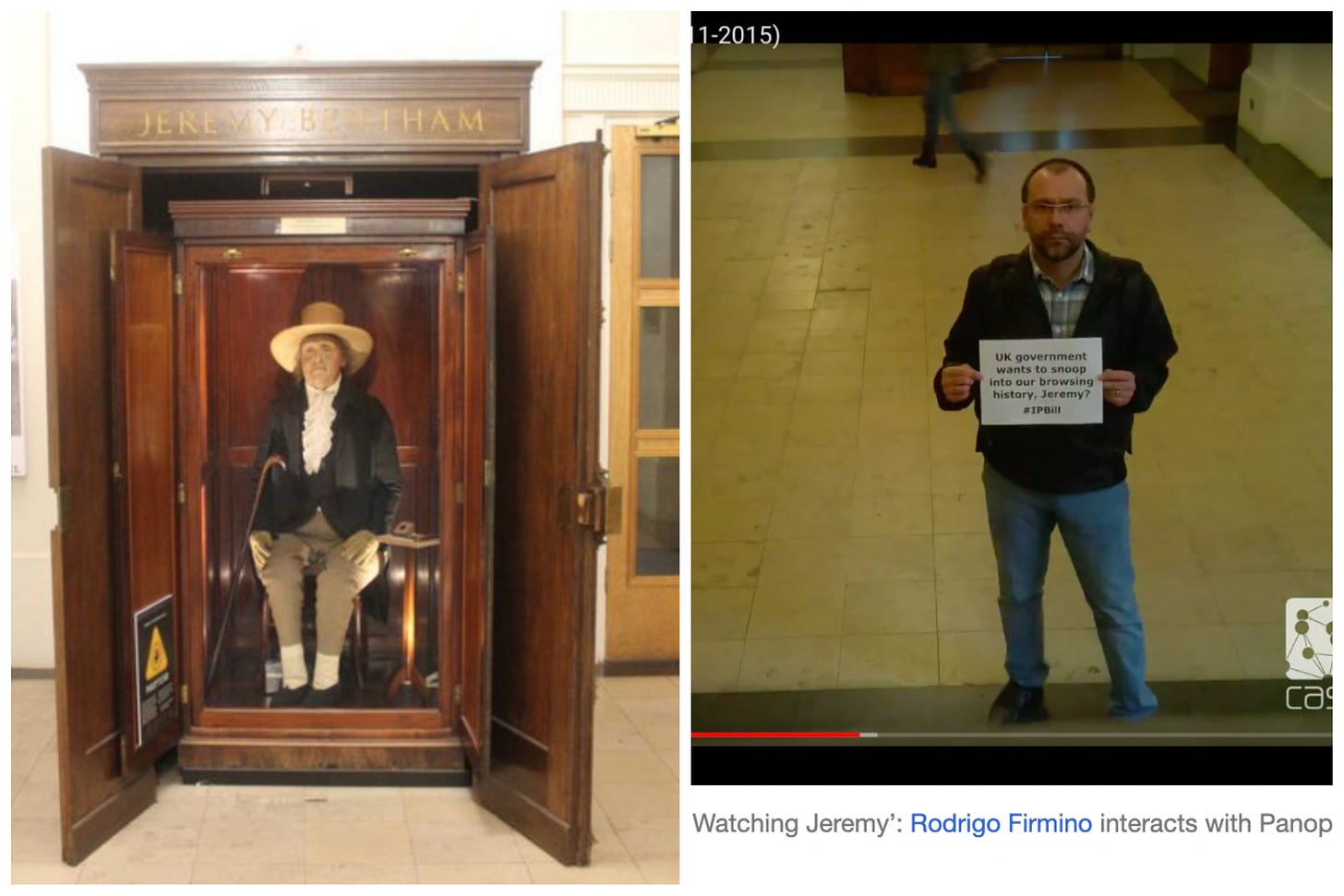

The design was never implemented in a UK prison, but the University College of London (UCL), where Bentham’s theories were popular, created a “tongue in cheek” version of the panopticon. Before he died in 1832, Bentham expressed his desire to be preserved and displayed at the university, and so it was. His clothed skeleton was topped with a wax head and placed in a glass-fronted mahogany case in the hallway of the philosophy building. In 2015-2016, it became the subject of a research project called “PanoptiCam” where a webcam was installed to monitor anyone standing in front of the case and signage informed viewers that they were being watched. What Bentham saw through the camera was live streamed online. The daily time lapse from Betham’s box, was designed to mimic his famous idea of how knowing you were being watched might alter your behaviour.2 According to the researchers, the project had a “genuine” research element to “test algorithms to count visitor numbers to museum exhibit cases using low-cost webcam solutions.” But the project went a little deeper than that and intended to raise “issues of the surveillance state, online observation, digital scrutiny, and the routine recording of public spaces.”

Bentham’s PenoptiCam set up in 2015-2016 at University College London (left) and Rodrigo Firmino (right) interacts with the PanotiCam in 2015. From the Archive of Daily Timelapses.

‘A pandemic of surveillance’

In his 2022 book, Pandemic Surveillance, David Lyon observes that while many forms of domestic surveillance existed prior to the pandemic, such as nanny cams, tracking devices for the elderly, and “smart” appliances, there was an “exponential expansion” in the forms of surveillance that arose during the pandemic. [They] “have grown and mutated so rapidly that their spread might be thought of as viral,” like a “pandemic of surveillance,” he writes.

Lyon is a former director of the Surveillance Studies Centre at the University of Ottawa, and professor emeritus in the department of sociology and law at Queen’s University. He is also the author of the 2015 book Surveillance after Snowden, and the author of the 2022 report, “Big Data Surveillance, Freedom and Fairness: A Report for all Canadian Citizens.

As was noted in Part 1 of this series, the pandemic—and the fear and panic that ensued—have been used by big tech lobbyists and governments to expand their power. Shoshana Zuboff, the author of the 2019 book The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power, argues that like the attacks of 9/11, the pandemic was portrayed as an exception, so all “concerns about surveillance, about privacy, should be set aside in favor of these companies being able to expand their role and somehow ride to the rescue.”

Recall, Zuboff’s book takes particular aim at Google, which averted impending doom during the dot-com bubble burst by taking all the “behaviourally rich” data the company had been collecting from users, and considered worthless, and turn it into gold. She called it a “new mutation” that “began to gather form and quietly slip its moorings.”

Essentially, Zuboff’s concern lies in the fact that surveillance capitalism’s capabilities are not just limited to extracting behavioural information, but has been expanding its interest in the behaviour itself—now wanting to use it for manipulation and control.

None of it would have been possible, says Zuboff, if it were not for Google’s (and others’) freedom from legal restraint.

Where Zuboff’s book leaves off, Lyon’s book takes over.

Lyon explains that the “level and range” of surveillance was “hugely augmented” by the lockdowns and stay-at-home orders because now there was much more domestic targeting as people were working from home, shopping online, and learning online. This all led to an increase in remote-working surveillance through work monitoring systems.

In his book, Lyon points to the “shock doctrine”—which holds that governments will frequently take advantage of shock events, like natural disasters or human conflict, “to bring about major changes that consolidate their power. Whether governments did indeed do this, “remains to be seen,” says Lyon, “and the question calls for serious investigation.”

But for Naomi Klein, who popularized the term “shock doctrine”—it was the title and subject of her 2007 book—the question of whether the pandemic was used to steamroll a digital transformation is undeniable.

Early on in the pandemic, Klein took serious issue with some of the policies implemented by New York Governor Andrew Cuomo in an article titled, “Screen New Deal – Under Cover of Mass Death, Andrew Cuomo Calls in the Billionaires to Build a High-Tech Dystopia.”

The pandemic was only beginning but New York state’s post-COVID reality was already being reimagined, “with an emphasis on permanently integrating technology into every aspect of civic life,” writes Klein.

In fact, when all was said and done, not much would go un-reimagined: telehealth, remote learning, remote working, the education system, digital commerce.

Klein writes:

Call it the “Screen New Deal.” Far more high-tech than anything we have seen during previous disasters, the future that is being rushed into being as the bodies still pile up treats our past weeks of physical isolation not as a painful necessity to save lives, but as a living laboratory for permanent – and highly profitable – no-touch future… It’s a future in which our every move, our every word, our every relationship is trackable, traceable, and data-mineable by unprecedented collaborations between government and tech giants.

In her article for The Intercept, Klein lays out how the massive public expenditures on expanding high-tech research and infrastructure was planned in the US two weeks before the coronavirus outbreak was declared a pandemic, but it soon underwent “an aggressive rebranding exercise.” She writes:

Now all these measures (and more) are being sold to the public as our only possible hope of protecting ourselves from a novel virus that will be with us for years to come… Silicon Valley had every intention of leveraging the crisis for a permanent transformation.

In his book, Lyon pays particular attention to how pandemic surveillance affects “ordinary people in everyday life,” and he says the biggest worry is how surveillance data – especially contact tracing and vaccine passes -- makes people visible to institutions, authorities, and companies that represent power. He also notes that data can reveal how employees are working, how students are performing, and what consumers are buying.

“The problem in pandemic surveillance is the same problem we have with surveillance in general in the 21st century, which is that it makes everyone more visible, more legible, more reachable, and more manipulable,” he tells me in an interview. “We’re seen as members of a group, not as individuals.”

Lyon uses the example of how vaccine passports, for instance—personal health information—could be used to further marginalize groups whose take up rate was lower. The ways that these groups “are made more visible would have an impact on the lives of such groups,” he writes. “This can also lead to other kinds of disadvantage, as marginalized groups are affected by disproportionate profiling, policing, and criminalization.”

Indeed, once vaccine passports were coupled with mandates, those who didn’t comply weren’t only denied access to public life, they lost their employment and were denied certain health services.3

Lyon says the pandemic brought us the “largest digital surveillance surge ever,” with “power being wielded in unfamiliar and intensified ways.” He also notes that pandemic conditions strengthened the “connections between government initiatives and surveillance capitalism… [which] may be hard to dismantle when the crisis has subsided.”

Ultimately, he raises the crucial question:

Whether the sun will set on pandemic surveillance or whether, as followed 9/11, there will be a substantial legacy of questionable surveillance for another generation to deal with.

In his book, Lyon also points to something that especially troubled me during the pandemic: we not only became “objects of surveillance, but subjects of surveillance.” People were checking each other for compliance regarding masks, getting vaccinated, and social distancing.

We were not only surveilled, we did the surveilling.

Public kept in the dark

The concerns raised by Zuboff, Klein, and Lyon are further echoed in a recent report penned by Privacy International, the European Centre for Not-for-Profit Law, and the International Network of Civil Liberties Organizations (INCLO), which lays out in no uncertain terms that there was a ramping up of surveillance and in many countries during the pandemic, as well as evidence of heightened authoritarianism. The study found that more than half of the world’s countries enacted emergency measures, which typically involved “increases in executive powers” with little to no parliamentary oversight, as well as “suspensions of rule of law, and an upsurge in security protocols.” The groups argue these impacted fundamental human rights, including freedoms of expression, assembly, association, privacy and movement. The authors also note that many governments used the pandemic as a pretext to further their own political aims.

In its global overview, the authors note that various technologies to enable widespread surveillance were deployed to greater or lesser degrees depending on the country, including contact tracing, quarantine monitoring apps, drone surveillance, digital vaccine certificates, SIM card tracking, wearables like electronic wristbands and bio-buttons, biometric technologies like facial recognition, and data scraping of social media for mentions of COVID-19. 4

Many of the technologies were rushed in, with little evidence of effectiveness, transparency, oversight, legal frameworks, or sunset clauses stipulating when they’d be phased out.

Essentially, based on information from many countries, as well as specific case studies from Colombia, France, India, Indonesia, Kenya, and South Africa, the authors identify five “overarching” trends during the pandemic:

· the repurposing of existing security measures like cybercrime laws to justify surveillance of online activity and increased powers to intelligence services;

· silencing of civil society through criminal penalties and monitoring public spaces;

· the influential role of private corporations;

· the risk of abuse of personal data;

· and the normalization of surveillance beyond the pandemic.

Surveillance was not only used to identify contacts, or those who broke quarantine rules, but to identify those who were spreading “misinformation” about the virus—a thorny subject we’ll return to in Part 3 of this series.

From the 2022 report, “Under Surveillance: (Mis)use of Technologies in Emergency Responses. Global lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic.”

Here in Canada, there were some egregious examples where data being obtained through pandemic surveillance were misused and, unlike the prisoners in Bentham’s panopticon, the public was not aware they were being watched.

One extraordinary invasion of privacy took place in early April 2020, when the Ontario government passed an emergency order that allowed the police to access names, addresses, and dates of birth of Ontarians who had tested positive for COVID-19. But people getting the tests weren’t told the information was being shared with police. Police had access to the personal health information database until mid-August when the portal was shut down as a result of a legal challenge by a group of human rights organizations, including the Aboriginal Legal Services (ALS), the Black Legal Action Centre (BLAC), the Canadian Civil Liberties Association (CCLA), and the HIV & AIDS Legal Clinic Ontario (HALCO).

According to the lawsuit, police services conducted more than 95,000 searches while the database was active, and Thunder Bay police accessed the personal health information in the database more than 14,800 times—a rate of access 10 times higher than the provincial average—even though the area reported a total of just 100 COVID-19 cases while the database was active. It begs the question, does the fact that Thunder Bay has a relatively large Indigenous population have anything to do with the excessive surveillance?

In a statement, Thunder Bay Police Service said they had a policy to check the COVID status of anyone who called for service, including anyone who the officer would be in contact with at that address or incident, because they had a shortage of personal protection equipment and knowing who tested positive for COVID allowed the officer to “ration” the equipment.

But the groups that brought the legal challenge described the COVID database for police as being “inaccurate, unreliable, and dysfunctional,” and stated it was “hyper-surveillance” and a form of “harassment” towards already discriminated against, marginalized groups.

Source: Letter from the Ministry of the Attorney General

Public interest in the context of data, a “slippery fish”

Another Canadian example where the public was kept essentially in the dark while flaws in outdated privacy laws were taken advantage of, was when the Public Health Agency of Canada obtained de-identified mobility data of 33 million Canadians from Telus to track population movement trends. Not only did the government not disclose to Canadians that it was doing this, but Telus didn’t ask permission from its customers either.5

An investigation by the Parliament of Canada’s ethics committee concluded that if government wants to “harness the potential of big data,” which is essentially the linking and analysis of very large datasets such as mobility data, “it should do so as transparently as possible by redoubling its efforts to explain to Canadians what kind of data is being collected, why it is needed, how it will be used, and how they can opt out of the collection if they want to.”

It also concluded that privacy laws in Canada are “in dire need of modernization.”

But also—and this is the key point—this modernization needs to be done with parliamentary oversight, transparency, and public involvement.

While experts in the information and privacy field call for privacy laws to be updated to protect citizens from what appears to be a clear and present danger – they also note that it’s important that these changes are made in the light day.

But the opposite seems to have happened in March 2020 in Ontario, when Bill 188—an omnibus bill aimed at dealing with the economic effects of the pandemic—also included, to the astonishment of many, significant changes to two access and privacy laws: Personal Health Information Protection Act (PHIPA) and the Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act (FIPPA).

The inclusion of the amendments to the access and privacy laws came as a surprise to most, including, astonishingly, the province’s Information and Privacy Commissioner himself. A few days after the omnibus bill received royal assent, Brian Beamish wrote that he was “surprised to see” changes were made to the access and privacy laws in a bill intended to address the economy.

Changes to the kinds of data that could be accessed in the name of public health, were essentially steamrolled through in a way that was intended be hidden.

It’s interesting to note that in his final annual report prior to the completion of his term as Information and Privacy Commissioner in July 2020, Beamish took the opportunity to point out that the province’s current regulatory framework was “ill-equipped” to “tackle issues of data governance and the protection of privacy rights,” and that the laws “have not kept pace with the current societal and technological reality.”

Teresa Scassa has written about the hidden amendments. She is the Canada Research Chair in Information Law and Policy at the Centre for Law at the University of Ottawa.

In an email correspondence with Scassa, where I ask her if the changes made to these laws were in the public interest, she replies that discussions about “public interest” in the context of data,” is a “very slippery fish.”

There is a clear public interest in governments being able to make well-informed decisions, particularly during a crisis. There is a clear public interest in being able to use certain data to look for solutions to pressing medical/health issues (particularly in a pandemic, but also beyond). At the same time, there do need to be safeguards to ensure that privacy rights are protected - and beyond privacy, that there is a level of public awareness and acceptance of both the goals and the means to achieve them. There are also important issues about how large stores of health data should be governed in the public interest.

Scassa says the omnibus bill changes in Ontario “were just the tip of the iceberg,” and that “Ontario is keen to do more with data for a range of purposes… particularly with respect to health data.”

“In the narrower context of pandemic surveillance, certainly part of the agenda was to make more data more easily accessible in order to allow governments to better understand and respond to the pandemic,” she says. “We’re starting to see the shift towards more access to more data for more purposes.”

I ask her if the public should be concerned?

Not in the sense of being opposed to any data sharing, but in the sense of being concerned that any data sharing that takes place be done according to legal and ethical norms, that there be appropriate oversight, and that cybersecurity is robust and appropriate. The use of large pools of data for research and data analytics purposes raises new issues around consent, social licence, public engagement, transparency, group privacy – and these issues need to receive attention.

Teresa Scassa, Canada Research Chair in Information Law and Policy at the Centre for Law at the University of Ottawa

In Beamish’s final report as privacy commissioner, he also referred to Toronto’s “smart city” project—which amounted to a public-private surveillance scheme—as an example of what can potentially happen when laws are outdated, or don’t sufficiently protect the public from unscrupulous surveillance capitalists.

While Toronto’s “smart city” project was initiated a few years before the pandemic, it’s worth taking a look at here.

The “Quayside Project” was an agreement between Waterfront Toronto and Sidewalk Labs, to create Sidewalk Toronto, a “living laboratory,” where 12 acres of “under-developed” land in the city’s eastern waterfront would be transformed into a digital wonderland. Important to note, Sidewalk Labs is a subsidiary of Google.6

The physical infrastructure of the neighbourhood would have a digital layer built into it. A network of sensors—embedded in street lights, traffic lights, roads and buildings—would include low-bandwidth thermometers, air monitors, radar, Lidar, location services, and high-resolution cameras that capture millions of pixels dozens of times per second. Sidewalk Labs promised “ubiquitous connectivity” to achieve “ubiquitous sensing.” Essentially, the neighbourhood project would capture a wide array of personal data from anyone who lives in it or enters it, 24/7.

Why? According to Sidewalk Labs, the digital layer would process the mass of data captured to analyze and predict human behaviour, “modelling how people make choices about where to live, where to shop, whether to own a car, or how to travel from place to place.”7[6]

The project was vociferously opposed by the Canadian Civil Liberties Association (CCLA), who launched a legal action saying, it “has the potential to set a precedent for all cities and city residents across the country.” CCLA:

We believe the question is not how to use tools of mass surveillance, but why we should allow them to be used at all.

The CCLA case included affidavits from privacy and information experts including Rutgers University’s Ellen Goodman. Goodman noted that Sidewalk Labs had plans for the Quayside data including, “introducing unique identifiers for individuals and organizations in the neighborhood, creating comprehensive data profiles for residents, using a social credit system to reward residents for good behavior with free and premium services, and using data for predictive policing.”

Goodman concluded: “There is insufficient digital governance to ensure that the Project will adequately protect the privacy of and secure the consent of the people of Quayside, especially in light of the recent history of technology company lapses in regard to these goals.”

In 2020, Sidewalks Labs withdrew from pursuing the project, citing economic uncertainty due to the pandemic. It’s unclear what role opposition from the CCLA played, but my guess is it wasn’t insignificant. The company continues to offer advisory services for real estate developments.

Sidewalk Labs rendering of Sidewalk Toronto. The surveillance cameras—the digital and most important layer of the project—are nowhere to be seen.

Nova Scotian’s Health Data Going Digital

Here in Nova Scotia the government recently announced a ten-year agreement worth $365 million with Oracle Cerner, an “integrated technology company” based in Austin, Texas. The government says the new system called “One Person One Record,” would consolidate patient information and provide better and faster patient care.

While the system proposed is indeed a digital one, the word “digital” does not appear anywhere in the government news release. Neither do the words computerized, or electronic. Instead, it’s simply called an “information system.”

But the system is indeed digital. Oracle Cerner’s Web site says, [the] technology has been utilized by more than 420,000 customers across 175 countries to accelerate their digital transformation.” [italics are mine]

In 2019, when she was still Information and Privacy Commissioner for Nova Scotia, Catherine Tully warned of the pitfalls of digitizing health records amid an archaic legal framework designed for a world that existed in 1993, five years before Google was founded, when there were only 130 websites in existence.

The plan for the province’s “one person one record” digital system was set in motion by the previous Liberal government under Stephen McNeil, and at the time, Tully said the government didn’t seek out her expertise to help design the digital record-keeping system. She also noted at the time, testifying before the all-party public accounts committee, that the province needed to modernize the Protection of Privacy Act because the law “will not protect Nova Scotians.” She wanted the provincial government to conduct a privacy impact assessment and reassess every step of the way to completion of the project.8

"They need to identify risks. They need to mitigate those risks. They need to circle back and make sure that privacy is protected.”

I reached out to the NS Department of Health and Wellness (DHW) to find out more about the new system and whether there’s been any follow up regarding Tunny’s concerns.

Here is the DHW reply in full:

One Patient One Record (OPOR) is a digital system. However, it also includes the development of new clinical standards, new devices and infrastructure, and the elimination of paper-based processes, all designed to help our healthcare professionals provide better care to more patients.

The Office of the Information and Privacy Commissioner (OIPC) was briefed on OPOR in August 2021. Vendor specific details were not discussed due to the confidential nature of the procurement. A commitment was made to re-engage once procurement was finalized which we are planning to do now that the contract is signed and OPOR has been approved.

In addition to consultation with the OIPC, the implementation of OPOR includes additional staff and external advisory support to complete a full Privacy Impact Assessment as well as continued monitoring and support of the privacy components of OPOR. We intend to consider the outcomes of consultation with the OIPC and the Privacy Impact Assessment during the design and implementation of the OPOR Clinical Information System.

Government has committed to a review of the legislation before Spring 2024.

So, let me get this straight: Nova Scotians’ personal health information will now be handled by one of the world’s largest private-sector providers of digital information systems, and Nova Scotians will be paying for it, but we won’t be privy to the details of the procurement because it’s confidential. As well, the privacy impact assessment, and a review of the privacy laws—which should have taken place before any deal was actually signed—will be taking place after the deal has already been entered into.

What could possibly go wrong?

[Stay tuned for Part 3 of this series, where I will dip my toe into digital identification schemes and wrestle with the viability of democracy in an age of surveillance capitalism]

Bentham quotes taken from Jeremy Bentham: The Panopticon Writings. (Edited by Miran Božovič).

The PanoptiCam project ended in 2016. In 2020, Bentham was moved to a museum-grade glass case in the UCL student centre.

There are so many examples of each of these types of technologies – too many to go into here – but I wanted to mention a type of “wearable” that was initially mandated for staff, faculty, student athletes and students living in residence at Oakland University in Michigan, to track and monitor COVID-19 symptoms. After a student petition opposing the university’s original plan to require the wearable technology, the administration decided the “advanced technology device” should be offered instead. The BioButton is worn on the chest, measures temperature and vital signs, and with the app on the wearer’s mobile device, combines this information with the wearer’s answers to a set of daily screening questions to indicate if users are cleared for regular activities or at risk for a COVID-19 infection. According to the university, the data was to be used to determine if the student is able to participate in campus activities.

For more on the PHAC mobility data story I recommend reading the three-part series by Bryan Short at Open Media.

Important side note: Google also has a project called the Google News Lab, within the Google News Initiative, whose “mission” according to its Web site, “is to collaborate with journalists to fight misinformation, strengthen diversity, equity and inclusion within news, and support learning and development through digital transformation.” Lion Publishers, in a partnership with the Google News Initiative, created the GNI Startups Lab, which provides six-months-worth of funding for “independent news publishers,” – including this one -- who then receive “training and coaching” in return. I’d love to be a fly on the wall of one of those coaching sessions.

Detailed information and quotes about Sidewalk Labs proposed Toronto project taken from Canadian Civil Liberties Association Michael Bryant’s affidavit in the legal challenge filed by the CCLA against the Toronto Waterfront Revitalization Corporation.

Another question worth asking is why are governments partnering with the private sector when they could be creating publicly-funded, in-house solutions to managing health information? It reminds me of Prime Minister Trudeau signing an agreement with Amazon Canada in April 2020 to manage the distribution of medical equipment. Apparently, Amazon said it was offering the service at cost. But why did the government bypass the public postal service?

I'm troubled by the seeming lack of public interest in this topic. I would have thought that the pandemic would have alerted more people to the danger of blind trust in government.