The Butterfly Effect

An interview with Columba González-Duarte on how the western model for protecting endangered monarchs has contributed to making Mexico's reserve a violent frontier

In September 2019, the day before hurricane Dorian was scheduled to hit Nova Scotia, I spotted the iconic yellow and black stripes of several monarch caterpillars on a cluster of milkweed in my garden. With strong wind gusts predicted in the 100km range, I made the quick calculation that the chances of them remaining anywhere near the leaves of the only plants they eat and need to survive, was next to zero. So, I decided to move them, along with the long stems of their host plant intermingled with some woody branches, into a greenhouse, where they not only rode out the storm, but formed chrysalises and eventually emerged as butterflies.

While the ultimate fate of the newly emerged butterflies remains an unknown, I’d like to think they joined the millions of other monarchs from all over eastern North America that migrated south to Mexico that fall. I’d like to imagine that they too managed to escape the cold, and clustered in dense colonies beneath the canopy of the oyamel forests and that in the spring—after a dormant period—they began the 8-month migration northward in search of milkweed. It’s a cycle steeped in mystery: between the spring and fall, four successive generations of monarchs are born and die, and somehow—using highly evolved navigational mechanisms—the migrating generation knows its way back to a place it’s never been to before.

One of the monarchs that emerged from a chrysalis inside my greenhouse. Photo: Linda Pannozzo

This past summer, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) listed migratory monarchs as endangered, saying the population has undergone a precipitous decline of between 22% and 72% over the past decade. This is attributed to both legal and illegal logging and deforestation to make space for agriculture and urban development, which has already destroyed substantial areas of the butterflies’ overwintering habitat in Mexico, and its breeding habitat in the US and Canada. Other threats to the species include changing climate conditions—specifically, warmer fall temperatures—disease, and the use of pesticides. The loss, across its breeding landscape, of milkweed is linked to the expanding use of herbicide-tolerant genetically modified corn and soybeans in the US and Canada, which constitute 92% and 94% of these crops, respectively.

Creating forest reserves that include the Mexican oyamel forests—a forest type that’s “crucial for the survival of the monarch migratory phenomenon”—seems a good plan to protect the species from extinction, but according to Columba González-Duarte, the reserve system is resulting in increasing levels of violence and criminal activity, raising questions about whether it’s helping the butterfly after all. In a paper published in World Development, the Mount St. Vincent University professor writes that even as she was doing her doctoral research on the subject, Homero Gómez Gonzales, who worked in the field of conservation and ecotourism at one of the monarch sanctuaries in Mexico was “disappeared.” González-Duarte writes:

Media and social media coverage reinforced a predictable narrative common to conservation sites worldwide: that loggers were to blame for Homero’s mysterious departure. Yet, having worked in the MBBR [Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve] for years, my local interlocutors and I knew that the alleged crime was more complex than a simple case of ‘‘loggers” disappearing an “environmental activist.” Rather, the disappearance of Homero and countless others in the area reflect a worrying rise of violence within the reserve associated with a growing presence of organized crime.

The murders of those working on behalf of the monarchs “brings together monarch butterflies, organized crime networks, state bureaucrats, international conservation actors, and local forest users,” she writes.

González-Duarte is a sociocultural anthropologist—a field that examines the relationship between humans and nature. For her doctoral research, she explored how different communities in Canada, Mexico, and the United States, “engage with at-risk monarch butterfly migration.” She is currently writing a book on the subject.

I met up with González-Duarte at Mount St. Vincent University just as millions of monarchs from eastern North America were embarking on what will eventually be a 4,000 km loop, overwintering in Michoacán’s and Estado de México’s oyamel forests before returning to their northern habitats in the spring.

Columba González-Duarte is a sociocultural anthropologist and assistant professor at Mount St. Vincent University in Halifax. Photo: Linda Pannozzo

[The following transcript has been edited for length and clarity]

Linda Pannozzo (LP): I wanted to begin by asking you about what got you so interested in monarch butterflies?

Columba González-Duarte (CGD): I think it was really my own location and biography as a Mexican student living in Toronto because I was doing my PhD there. I wanted to do something that would connect me with my country and with my previous experience of traveling from south to north, and I wanted to connect my research with my own home and movement. When I found the butterfly, it just kind of connected.

LP: Creating a butterfly reserve in Mexico’s oyamel forests would appear on the surface to be a good thing. But in your paper, you point to the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA)—which arguably marked the beginning of neoliberalism in North America—as being one of the culprits behind the undermining of local governance and rural livelihoods that also allowed organized crime to gain a foothold in the butterfly reserve. Can you walk us through what happened?

CGD: Yes, and it is not a simple story, but I try to highlight some of the biggest consequences for those communities in terms of the neo-liberalization of nature and also policies. We have a move by environmental agencies—big NGOs and scholars—to think of nature and nature conservation in neoliberal terms and that means that it is basically granted a value which, as you say, it will be seen as something positive. But the moment in which we value nature only through its economic weight, it brings other sorts of problems to communities that have not valued nature in that way. So that's one of the things that happens with neo-liberalization and the creation of this reserve. It protects nature through an exchange of money. So basically, they give money to people in exchange for protecting land or not chopping down trees. But that money is not enough, and that money, in a way, confronts communities because it introduces a different cash economy, but also introduces a new concept of ‘why should I care for this nature?’

So that's one thing that we have going on in many reserves, not only the Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve, which follows the Biosphere Reserve model, which is a UNESCO model, which was planned in a Paris meeting. So, it's very much a western-centric idea of nature that has been replicated across the world through this reserve model. And at the same time—and this is not a coincidence—we also have a move to a neoliberal North America. With NAFTA we have this economic block that functions to contain certain movement but also allows other movements, all with the idea that if we have free trade across nations, we will have more growth, more employment, a better North America. I'm not saying that that's completely untrue. There are things that have happened in free trade that I guess we can say benefit some communities. What we don't have is a good system to distribute those benefits. So, poor North Americans have been the ones that have suffered the weight of that shift. We have a lot of science showing up that proves the move to neoliberal North America also means nature degradation. We have climates and environments that are no longer what they used to be because we have more mono-crops, more pesticides, more herbicides, more conversion of land towards especially mono-crops. So, we have ecological degradation that goes beyond borders, and ends up affecting monarchs as well.

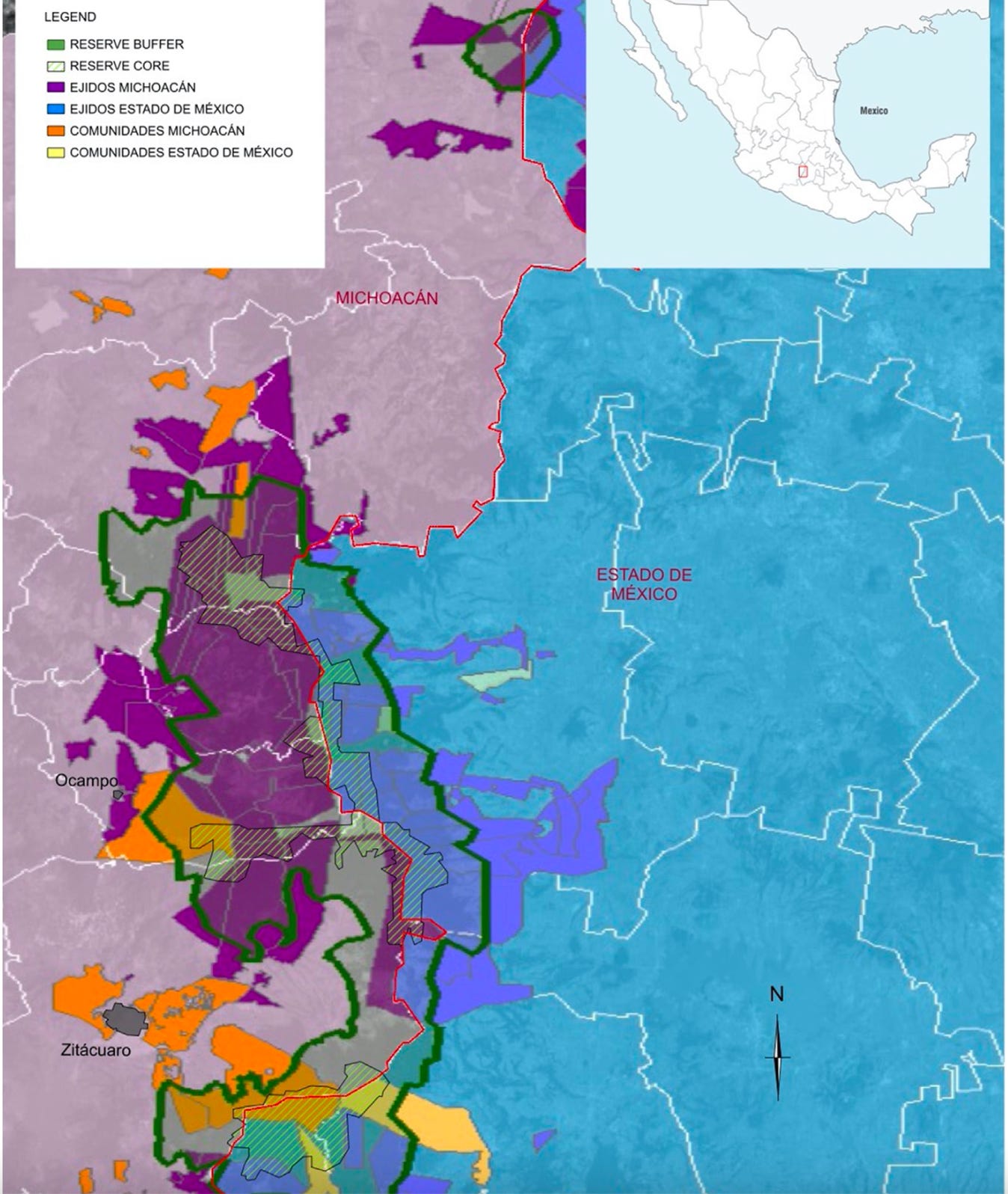

Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve (MBBR) In September 2000, the Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve was enlarged to cover 56,259 hectares, with core zones (diagonal light green stripes) of 13,552 hectares and buffer zones (demarcated with a dark green line) of 42,707 hectares. According to González-Duarte, the different colours illustrate the distinct social properties (mestizo or indigenous) and the two states of Michoacán and Edomex. Map courtesy Columba González-Duarte.

LP: How did the creation of the reserve itself lead to organized crime gaining a foothold?

CGD: The Reserve started in the eighties and the first bans were a complete ban—people could not use any parts of the forest and these have been forest communities for centuries. Then they shifted to the model that we have now, which is the biosphere reserve model that has a core and a buffer area. So, the core is reserved for scientific purposes that in theory no one can go into. There are even stories that people told me of fences that they tried to put up just to protect that core area. In the buffer area, they allow some activities. Either way, the core or the buffer area introduce a new form of managing and governing land that implies less [human] access to the forest, to put it in simple terms. So, people through the years, although they resisted, although they really didn’t like it—and they took different political measures to resist the reserve—they ended up [accepting] the model and that means there will be less human presence in the forest.

That means just walking through the core area became a crime. So, people stopped going. Through the years of having this new way of governing the land, we have in parallel—and it's not again a simple coincidence—the emergence of transnational organized crime networks. We shouldn't see what happens in Mexico as an isolated problem. Actually, the emergence of organized crime is in response to the failed war on drugs, but also in response to the demand for those drugs in the US and Mexico and the policies that we have at the North American level. So, eventually these networks reached the [reserve] area, and because these lands are unoccupied and people are having less presence there and also having trouble organizing themselves, there’s a kind of in-between gap that really allows organized crime to take part of these lands. Organized crime is taking lands everywhere, but it just makes it easier for them. So, what I often say is that conservation tries to stop deforestation, but actually fuels more deforestation by creating a fertile ground for organized crime that eventually, for the reserve, is also involved in deforestation.

Other parts of Central and South America go through similar processes. Organized crime entering in networks of cultivation, but not necessarily only of drugs. Then the cartel has the power to transform that landscape easier. What we see is that the environmental organizations that should in theory be policing the deforestation, they just can't because these are very powerful actors. They are armed. They are related to larger networks. So, it's one thing to criminalize a peasant because they crossed a boundary, but to really face the presence of organized crime is another.

LP: In your paper you mentioned the disappearance of Homero Gómez Gonzales who was involved in the Reserve. Was his death and disappearance one of the reasons you wrote the paper?

CGD: It inspired me to rewrite that paper, because it was a paper on violence and at the moment I was writing the paper, he was alive, and then we have a man who has disappeared in this context and we have this butterfly disappearing. So, I knew I had to bring in his story. Someone killed this man and that's likely because of the infiltration of organized crime in the area. But he is also not the only case, there were other deaths that occurred.

LP: Yes, I read that there were others after him, tour guides, that were also killed, is that right?

CGD: Yes, they are probably the ones carrying out activities to watch the forest. So those tour guides are also forest watchers. So it could be that they were just walking on their land and they see something that they shouldn't have seen. So, there are more people currently who are targeted based on those environmental activities, but also in their need to care for this forest. We have this concept that they want to protect the forest. Well, they want to protect their home and that's a more accurate way to put it. Their home includes the forest.

Homero Gómez Gonzales was the head administrator at the El Rosario monarch butterfly sanctuary in Angangueo, Michoacán.

LP: How were the forests within the current butterfly reserve used and “managed” before 1980, when the reserve was first created and how do you think the pre-reserve, more traditional way of life affected the butterfly population?

CGD: On how it affected the butterfly population, we really don't have data. But I'll tell you how it is, and this is actually in a paper that has been pre-accepted with my colleague Roberto Méndez-Arreola, in the Journal of Political Ecology, in which we are describing that relationship with the forests. People have different experiences, according to the communities and indigeneity. It's important to understand that we do have mestizo communities, which in Mexico have, to put it in simple terms, more settler worldviews than indigenous communities do. In reality, they often mix and do very similar things in terms of land management or traditions but we do have ethnicity recognized in this area as different land access and they actually name their land differently, for example, and their practices will be different. We study indigenous practices around corn (milpa) as a form to review monarch butterfly conservation.

For indigenous communities accessing the upper forests is a way of getting other resources, [such as] mushrooms, collecting the wood for cooking and other purposes, medicinal plants maybe doing a little bit of hunting, which is now becoming super hard because there's just no animals around. So, they would hunt and gather resources in the upper forest where the butterflies arrive and then in the lower hills, they would have the corn cultivation. So that's a model that we know was working in that area for centuries and that we know that indigenous communities keep these days. And that model was seen as not good for nature, because just the idea of converting forests to current cultivation was seen like, ‘you're chopping down trees.’ But actually, we all need to chop down something in order to live. And when you have that corn cultivation in the lower areas, you have a really nice ecosystem that provides a lot of diversity, humidity and food for the butterflies, and then you have the upper forest which provides that shelter for butterflies and many other species.

So, when we see it through time, part of what we're saying in this piece is, environmental science of that time [period], being western-centric, had this fight against these milpas and corn, but if we assess this after years, that sort of connected biodiversity between the milpa and the forest was probably good for humans and non-humans. So, we're trying to push for a recognition of the milpa system as a sustainable production model because it also allows people to stay on their land. If you have a good milpa system, which is corn, squash, beans, medicinal plants, we do know that people can stay on their land easier than people who have their land converted to monocrops, which are unsustainable and [result in] a need to migrate locally, nationally or internationally.

LP: In your study, you make reference to another paper that found that when the butterfly reserve was created in 1980, the communities were allowed to “maintain ownership devoid of the rights that define ownership.” Can you describe what this meant in practice? What happened to the local inhabitants once the reserve was created?1

CGD: Instead of doing what happens in other reserves here in North America, and in other continents, of either forcefully taking the land in exchange for small payments, or even sometimes without payment, here [in the butterfly reserve] they didn't do that. They allowed them to stay on the land and because the ownership of the land was communal ownership, they couldn't buy it. So, they let them keep the titles, but they then imposed a model that doesn't allow them to do anything with the land, which is probably more scandalous. It’s really interesting to see, that because they kept ownership, even without any rights attached to it for decades, at least now we’re seeing some indigenous communities able to claim their land back, to be able to manage the land in their own way. So that's going to be an interesting shift, and that's just happening now.

Monarch butterflies densely clustered and overwintering in the oyamel forests of Michoacán, Mexico. Photo from the Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve, UNESCO.

LP: You write about the “policing of nature”—where poaching and deforestation are viewed as crimes—and you discuss how this is often done through military or paramilitary means and sometimes through NGOs like the World Wildlife Fund, and that this policing actually creates “fertile ground” for activities like deforestation. Can you explain?

CGD: We see the policing of nature in different conservation areas across the world. In some of those areas that become either international protected areas, or government protected areas, there’s some form of extra organism that will be watching for that conservation. They often introduce military to just watch and observe their new land regimes, and when they don't have military available or they can't, they probably just outsource that activity to paramilitary groups, which often are also associated with organized crime networks. So, what we have seen is that introducing those policing entities in conservation areas ends up, in many cases, in a tension and the emergence of even more violence. It also criminalizes small scale poaching, for example, and rationalizes a form of criminalizing people. There’s profiling of who becomes a criminal in these cases, of course, which is based on race or class. So, there’s a whole critique in conservation studies about policing nature: that we shouldn’t be protecting nature through force. We should find other mechanisms like consensus that does not allow for these forces to enter. Because once they enter, we tend to see that it really is not good for nature and it's not good for the humans.

In the Mexican case, we don't have a clear paramilitary force, it's possible that it will emerge. But we do have military and police entities. We have environmental police, but when they can't because they are understaffed, they will call the military, and they tend to be opposed to the emergence of local indigenous self-defence groups, who guard the forests and protect the land.

LP: You write about how ecosystem services payments are only paid to those who own land, and who are “compliant” or following all the rules, and that this is deepening social tensions and stigmatizing those who are poor and landless. Tell us a bit more about the unintended consequences of these payments?2

CGD: The early stage of ecosystem services is really mediated by economics— the idea that humans will only value nature if they can put a monetary figure on that nature. So even the concept of services means [nature] has to provide me with something. It's also very anthropocentric: it is thinking in terms of what nature offers to the human and not why it deserves or has the right to exist. So, it's really a western-centric anthropocentric concept mediated by economics. I see the need for having some sort of framework to protect nature. I agree with that. I don't think ecosystem services is exactly the right path, but it is changing and we're trying to think through it differently.

So, when I did my work at the Reserve, I saw communities who are actually confronting each other for these little pennies, because that's what they get, a few dollars for the protected trees. And WWF was not wanting to see, but at the same time kind of happy that the communities are actually confronting each other to see who protects that tree. When the value of human life has less weight than the value of that standing tree, there's something wrong with the way it gets implemented. Don't get me wrong, it's not an easy task. I wouldn't want to be WWF working in this area. It's a complex task, but it's clear to me that they didn't value the communities that also have their own right and value to be there, and they didn't even consider there could be other forms of valuing nature, which does not imply an economic exchange or an idea of services. That has not happened on the reserve. We're working towards it and I hope one day we have that.

LP: So, what would you see as an alternative?

CGD: I actually co-wrote a paper about this in Conservation Letters, [a Journal of the Society for Conservation Biology], and we looked at what the inequalities are of implementing these policies, especially in the Global South.

We need to think in terms of something that is good for the humans and more-than-human communities. If we keep thinking we're going to protect nature from humans, I don't think it's going to work. We need to move to a system that protects species holistically, including the human communities.

Monarchs clustered on the oyamel trees. Screen shots taken from film, Flight of the Butterflies.

LP: What role do avocado plantations have in all this?

CGD: Avocado are not exactly native to this area. It needs humidity, heat, lots of water but the frontier for growing avocado has been increasingly extended. It's not ideal. It's very similar to what happened to coffee crops: they were good in one area but they started being demand by the Global North extensively, which means people start extending that frontier, growing more coffee crops in areas that are not ideal for coffee, with chopping down rainforests to give the light that it needs, for example.

In this [avocado] case, they chopped the trees and the biggest problem, if I can point to one, is the amount of water avocados need. So, they're demanding a lot of water, which means many other communities and crops and species don't have the necessary water. And what we do see is that if 15 years ago, the avocado frontier was near the [butterfly] reserve, once organized crime entered in that business, they are much more powerful. They are fiercer. They don't care about the law in the same way. They are transforming the land quicker and so they have expanded the frontier to the reserve area and the authorities can do much. It’s very complex how they manage to convert the buffer land legally to grow crops. So, once you set fire, for example, in an area and you say, ‘Oh, this area cannot be used any longer for the buffer activities that were allowed. Now we can have avocado plantations.’

LP: And nobody looks into how the fire started.

CGD: Exactly. People have told me about that. That could be one of the options that they take. But there are very complex mechanisms that are slowly encroaching the reserve. What we do know is that we have different actors involved: we have the communities themselves. Some of them want to cut the forest because they don't have any other access. They lost their access with the reserve. So, to me, it's one of those unintended consequences of conservation. When you withdraw people from their own rights to manage their land, you can have this kind of backlash.

LP: The title of your paper is “Butterflies, organized crime, and ‘sad trees.’” What are ‘sad trees’?

CGD: So, people told me these stories of how they had a relationship with the forest. If the trees were sick because they have a pest, then they will control the pest and do some management of the land. They will go and cut branches. So, when they intervene, they care for those trees, and they actually look healthy and happy. They often say, this forest looks unhealthy, which is very interesting because it really contrasts with the concept of a protected forest, and that if you don't intervene, it will be a healthy forest.

LP: Do the communities view the butterflies wintering in the upper forest as being connected to their gardens, the milpa, because the butterflies are pollinators?

CGD: We haven't found the pollinator references, it’s an interesting one. What we found is that the butterflies arrive on the Day of the Dead. So, people will tell you that the butterflies, when they arrive, they carry the soul of their ancestor because they arrive in November when the people celebrate that.

LP: That’s beautiful!

CGD: Yes, it’s beautiful. Part of what I've been researching is to analyze that relationship between the butterfly and Day the Dead, which is not exclusive to monarchs. It is actually present in pre-colonial Mexico with many butterflies. Butterflies are the carriers of their ancestors. But it’s also not a coincidence that Day of the Dead happens at the end of the harvest season. So, not pollinator necessarily but she's [the monarch] pointing out the end of the harvest. Then the butterfly stays in this forest from November to spring and it departs when the corn cycle starts again.

So, to the people, when you ask them, ‘What's the importance of this butterfly?’ they will tell you they are related with the harvest season: They come, they tell us that it's time to harvest and when they leave, this tells us that it’s time to start a new cycle. We find this in connection with other species as well. There are ants that also tell us that it's time to do this and that with the land. So, the butterfly is another insect that is part of that ecosystem, that is part of that harvest cycle, and that's kind of the value it has. It enters into the rituals to the forest, the cultural value of corn, which is what regulates almost all social life here in these communities. And that's the value it has; it reinforces the whole idea of a sacred corn harvest cycle in which humans and other entities unite.

Day of the Dead figurines featuring monarch butterflies. Wiki commons.

LP: So how should a conservation program for monarch butterflies address the problem of threats to the species at a North American level?

CGD: It has to be conservation beyond borders in a concrete way. We cannot keep conserving this butterfly or trying to protect this butterfly by nations, which is what we have now. We do have a couple of transnational policies, but they really always end up facing the problems of a nation state that has different regulations, different political aims, different momentum. So, to me, what the butterflies in a way are saying is, ‘The problem is probably the border itself.’ We need a revision of our concept of borders and who gets to cross them and that applies for the human, and likely it will apply for this butterfly, and we can benefit both. I kind of resist the idea that we can have a policy to protect these butterflies if we don't have a policy to protect humans.

We also need to create corridors. It's interesting to see that lots of people who are butterfly enthusiasts, amateurs, or already working in environmental activism, are providing commons—they find them somehow—to have habitat for this butterfly.

I wrote a piece for the Los Angeles Times and a number of people wrote me from the US saying they are trying to transform the landscape to be a space in which they can provide interconnected habitat for butterflies. And although I knew that was happening, it was just touching to see that a lot of people are thinking about how they can at least keep part of these lands to create a butterfly habitat. So, yes, it could be that those small initiatives of having butterfly habitat that is interconnected implies that we use our parks differently, our sidewalks differently.

LP: What about regulation? What role do you think government regulation has in protecting the monarchs -- banning certain pesticides, for example?

CGD: They’re so far off from happening, but yes, we have better regulation in Canada. Mexico, for example, now is much more progressive than what we have in the US. But the reality is that the US is the one that has more breeding habitat, especially for monarchs. We really need to assume that we need to work transnationally, and that's a big challenge. But if we don't get the US into herbicide control—not banning but at least more control—it's going to be tremendously hard because we do know that mono-crop extension herbicides and pesticides is a driver. The other one is habitat loss from development and housing and things like that. So, we need policy, but we need a policy that is the same and equal in the three countries.

Monarch caterpillar and chrysalis, sheltering in my greenhouse from hurricane Dorian. Photo: Linda Pannozzo

Hernández, M., & Merino, L. (2004). Destrucción de instituciones comunitarias y deterioro de los bosques en la Reserva de la Biosfera Mariposa Monarca, Michoacán, México. Revista Mexicana de Sociología, 66(2), 261–309.

The idea behind Payments for Ecosystem Services (PES) is, essentially, to pay landowners to protect their land in the interest of ensuring the provision of some “service” rendered by nature, such as clean water, habitat for wildlife, or carbon storage in forests. It is a promising conservation strategy, but as it’s currently been implemented, appears to have many pitfalls, with lots of room for improvement. To find out more about how well the use of ecosystem services payments is working to conserve and/ or protect land you might want to check out this excellent summary of 38 studies from the scientific literature on the subject: https://news.mongabay.com/2017/10/cash-for-conservation-do-payments-for-ecosystem-services-work/