“If there is any hope for the world at all… it lives low down on the ground, with its arms around the people who go to battle every day to protect their forests, their mountains and their rivers because they know that the forests, the mountains and the rivers protect them.” – Arundhati Roy (from The Trickledown Revolution)

Seventy-six days.

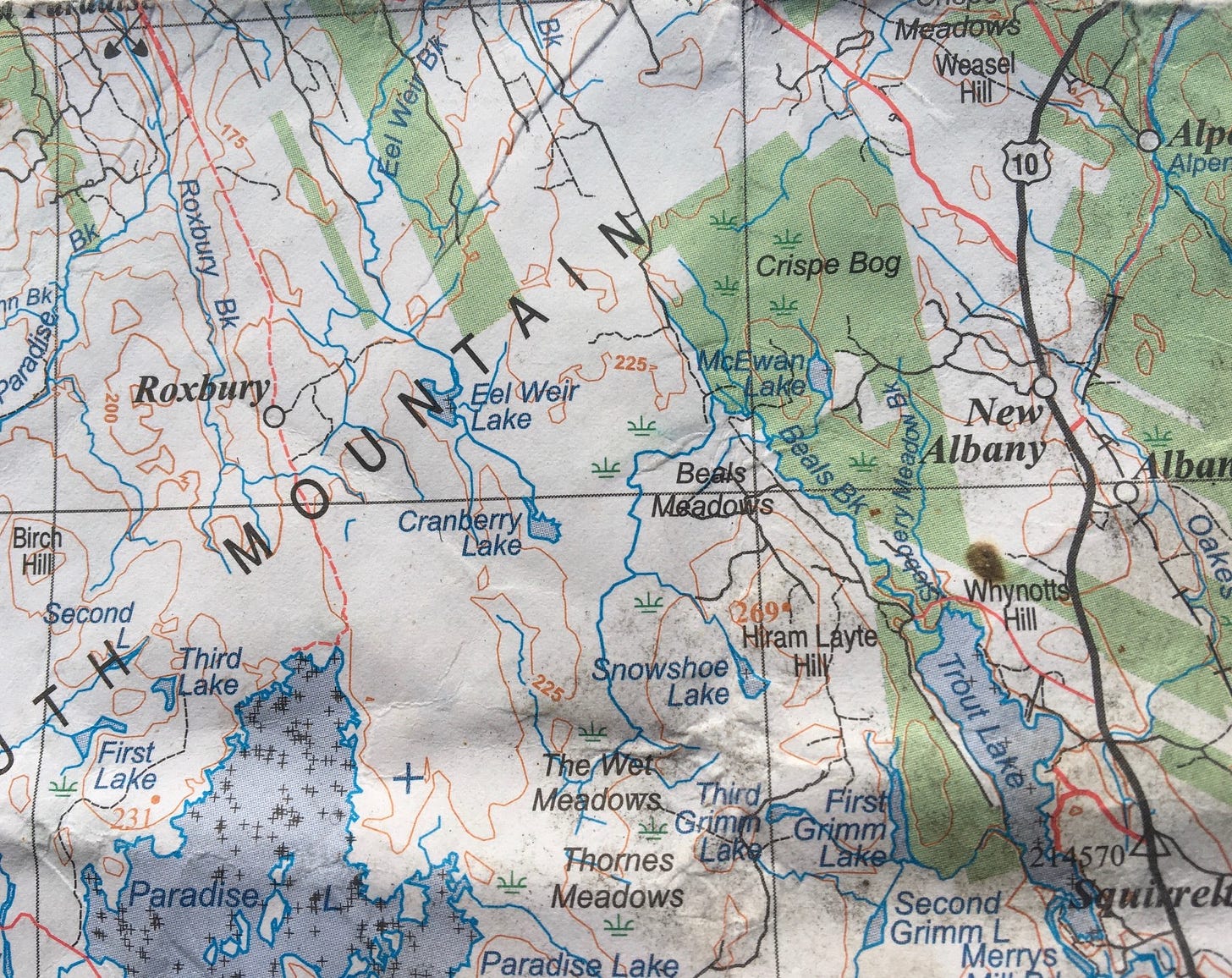

That’s how long a group of protesters led by Extinction Rebellion have been camped near Beals Brook on the South Mountain in Annapolis County, Nova Scotia, about a half hour drive from the town of Middleton. In early December, after learning that a 24-ha parcel of 80-year-old forest was slated to be cut, the group mobilized, got in just ahead of the feller bunchers, and have occupied the site ever since. The protesters say the forest provides important habitat and a wildlife corridor for species at risk, including the endangered mainland moose, pine marten, wood turtle, and, as it turns out, several species of rare lichen. The forest also borders a number of wetlands including Crisp Bog, and Beal’s and McEwan’s Meadows. Wetlands are one of the most endangered ecosystems on the planet.

“Forest protectors,” from the left, Keith Joyce, Barrie McGregor, Richard Amero, David Arthur, Tom Amero, Sandra Phinney, Janet McLeod. Photo courtesy: Nina Newington

The encampment itself sits on storied ground. A local resident, whose family goes back seven generations tells me that by the early 1900s, urbanization and development was encroaching on the forests and having an impact on moose. “All the game was gone, but not in the Beals Brook area,” he recounts. So, in 1923 a cabin was built there and became known as the “The Last Hope Moose Camp.”

“The village residents headed to that camp to get their winter supply of meat. It was their last chance, their last hope of getting meat for the winter.”

Nina Newington is a member of Extinction Rebellion and one of the “forest protectors” camping out at Beals Brook. To acknowledge that the land is part of Mi’kma’ki—the ancestral territory of the Mi’kmaq people—the group placed a flag pole about 5m from the old cabin spot, representing the “7 Districts” of the Mi’kmaw homeland—Kespukwitk, Sipekni'katik, Eskikewa'kik, Unama'kik, Epekwitk aq Piktuk, Siknikt, and Kespek.

“Bowater bulldozed [the old camp], so the ground there is uneven,” says Newington. “We are spread out next to that spot, plus have an overnight tent platform just above it. We are finding lots of bottles from the camp just above the levelled-out area where we are camped.”

Bowater is the Liverpool pulp and paper giant that was founded in 1929 as the Mersey Paper Co. by industrialist Izaak Walton Killam. By the time the mill shut down in 2012—selling all its assets to the Nova Scotia government—it was known as Resolute Forest Products. The deal included nearly 600,000 ha (1.5 million acres) of land holdings in the western part of the province, of which the Beals Brook lands are a part.

Beals Brook area became public land in 2012. Photo courtesy: Nina Newington.

At the time of the land transfer, public opposition to the practice of liquidating the province’s forests had been brewing for years. With Bowater’s lands now in public hands, many argued that a unique opportunity had presented itself. For instance, the Buy Back the Mersey Partnership, which brought together more than 30 groups and called on the government to buy the lands, was hoping it would protect the ecologically sensitive areas and explore options for community forests and value added industries.

According to the “forest protectors,” Bowater itself had recognized that the Beals Brook forest was of high value to wildlife when it agreed, 22 years ago, not to cut it.

But in the fall of 2014, anyone who was paying any attention could see the direction the wind was blowing. At the time, with Bowater’s former woodlands manager Jonathan Porter at the helm of the department holding the fate of the newly acquired crown lands in its hands—the government announced that half of the former Bowater lands would be allocated to WestFor, a new consortium of 16 mills (today it’s 12) and other wood companies.1

Last year, the government granted WestFor approval for a shelterwood cut on the 24-ha forest parcel at Beals Brook, which means 30% of the stand would be removed.

The idea behind shelterwood harvesting is to leave some of the established trees to allow for new seedlings to grow in their shade or to remove all the mature trees leaving behind some of the young seedlings. Either way, eventually the mature forest is removed to make way for an even-aged forest. Since shelterwood cuts don’t come with a guarantee that the remaining forest will be protected indefinitely, any benefits that might be achieved—such as retaining ecosystem services or ‘life-boating’ habitat for species at risk—are likely only short-lived.

As well, the 30% wouldn’t likely include any extraction roads or the widening of the main road. It also presumes that the regulation width of 20m for buffers adjacent to watercourses is sufficient. But even DNRR’s own science finds this width inadequate.2

According to wildlife biologist Bob Bancroft, “about three-quarters of our wild animal species either depend upon, or prefer, habitats near water… and these long, relatively narrow ribbons can contribute a relatively small amount to the total available habitat, but their wildlife value far outweighs their size.”

Moose, for instance, need a 50-60 m buffer between a clearcut and water before they will even use it, he says.

Furthermore, if the government is implementing ecological forestry—as the 2018 Lahey Review of Forest Practices recommended—then it calls for action “both at the operational level of forestry and at the landscape and provincial levels.” In other words, clearcutting has adverse cumulative impacts on ecosystems and biodiversity. It also results in a highly fragmented forest landscape, which harms wildlife.3

And the Beals Brook forest is surrounded by a sea of clearcuts.

According to Newington, even though the proposed cut for this forest is not a clearcut, “the extraction roads alone will devastate the wildlife value of this fragment of standing forest,” she says. “We can’t afford to stand by and watch more habitat for endangered species destroyed.”

The protesters want the government to consider the 24-hectares for protection.

Map indicates forest cover loss between 2000 and 2020. The core area (green) indicates the area the “forest protectors” want protected. It stands in sharp contrast to the patchwork of pink (clearcuts). Global Forest Watch.

Rare lichen a sign of ecological integrity

Day 56 at the Last Hope Moose Camp brought some welcome news, when the government announced a temporary “hold” on the plan to log because some rare lichens had been identified in the stand.

Black foam lichen, wrinkled shingle lichen, and frosted glass whiskers were located in the Beals Brook forest by a lichen enthusiast, and all are designated species at risk.

The DNRR was alerted to the discoveries, and it contracted lichenologist Chris Pepper to visit the site to confirm any/all occurrences and review the surrounding area near the harvest for other potential occurrences.

Before the temporary hold on logging can be lifted, 100 metre buffer zones would have to be applied around the trees hosting the rare lichens.

In an update issued on February 14, Newington confirmed that Pepper not only confirmed the initial discoveries, but he found more. “There are so few forests of this age or older left in the province,” says Newington. “Clearly DNRR needs to authorize a proper survey here when it is possible to see the whole trunks of trees,” as they are currently buried in 60 cm of snow.

When I contacted DNRR for comment on Pepper’s findings, a spokesperson said the department had not received or reviewed the data yet, but that it would apply a buffer zone to “any confirmed occurrences of rare lichens, in accordance with Special Management Practices (SMP) for this species, prior to the temporary hold on harvest approval being released.”

Newington questions whether placing buffers around these species is adequate protection.

“The discovery of three species of rare lichens in adverse conditions (lots of snow on the ground) confirms the high conservation value of this site. It reveals the inadequacy of DNRR’s monitoring of sites for Species at Risk, and more generally highlights the necessity of a freeze on harvesting on ‘crown’ land until the landscape level planning Lahey calls for has taken place. Specifically we need to decide what areas are available for harvesting before deciding what kind of harvesting will take place.”

Wrinkled shingle lichen ( Pannaria lurida). According to Frances Anderson: “It’s big and leafy and can colonise a large portion of a tree trunk. It is a cyanolichen, a lichen whose algal partner is a nitrogen-fixer. It's brownish, thick, and is usually fertile, that is, it has fruiting bodies on its upper surface where the fungal spores are produced for reproduction… Found on red maple and poplar on the Atlantic coast, red oak further south and up into Digby county and poplar in Hants. It prefers mature trees, and damp habitats. Photo courtesy: Brad Toms.

Brad Toms is a wildlife biologist with the Mersey Tobeatic Research Institute (MTRI), an organization that leads a government- and industry-funded research and monitoring program for the endangered boreal felt lichen (BFL). Toms says that for the three rare species identified at Beals Brook, “monitoring for survivorship” is just beginning and so it’s not yet known if a 100 m buffer is even adequate for these species.

For instance, when the recovery strategy for boreal felt lichen (BFL) was first developed in 2007, the team recommended a SMP where a 100m no-cut buffer be applied to reduce the “edge effects” caused by forest harvesting. As previously written, by 2013, it was discovered that the 100m buffer wasn’t working. When these areas were followed up, the islands of lichen habitat remained, but the lichen were dying. Nova Scotia government scientists reported that industrial scale clearcutting nearby was altering the light, wind, and temperature—essentially the microclimate—of these sites, making them less hospitable to the species. They concluded the buffer for BFL should be wider. Eventually a 500m buffer with two zones, was eventually adopted.

According to Toms, lichenologists and ecologists are often able to “read the forest.” He says an important common characteristic among the habitat of the three lichen species identified at Beals Brook is what he calls “site permanence.”

“Whether upland or forested wetland these sites consistently seem to be sites that have not had any major disturbance in a long time in the area around the lichen host tree. So while not 'old growth' by provincial definition these are forests that have been allowed to be in a natural climax state for an extended period of time possibly even longer than 'old growth' forest with longer lived species.”

Toms says that when forests have a major disturbance (natural or anthropogenic) the lichen diversity usually takes a hit and is “often altered for a long time and takes likely on the scale of a hundred years (or more) to be restored.”

“We can see today in cuts that have grown back from harvesting, blow downs, and insect-caused tree moralities from the mid 20th century, a lack of rare lichens and a much lower diversity and abundance of common lichens,” he explains. “There are gradients of disturbance we observe but in terms of lichen diversity and abundance, the difference between a 60-year old forest recovering from a clearcut 60 years ago, and [lichen diversity] in an undisturbed Acadian forest is stark.”

Black foam lichen (Anzia colpodes). Frances Anderson: “Dense with a lower surface full of holes, like black foam ( more like a sponge, but foam is more evocative). At the tips of the elongated lobes are little black dots, called pycnidia, which are vegetative reproductive structures. It very much likes moisture, and is often found at the edge of fens and wetlands in hardwood and shrub stands where it gets leafy protection from sunlight in summer, but plenty of light and moisture in winter, spring and fall. It likes red maples, red oak, and white ash. Photo courtesy: Nina Newington.

Frances Anderson is the co-author of the field guide Common Lichens of Northeastern North America. She says the three rare lichens found at Beals Brook are ones that prefer damp areas and are often found on the edges of wetlands or in treed swamps. “They prefer old, not necessarily large, deciduous trees, commonly red maple in some parts of the province, but in this instance, red oak.”

“All three of these lichens rely on ejecting fungal spores that have to find the right algal partner in a habitat that maintains the spores' variability,” Anderson explains.

In other words, when the fruiting bodies shoot out the spores, the spores in turn have to find the right algal partner in order to reproduce. If the microscopic spore finds the right microscopic partner, it then has to find the right tree with the right conditions, and those conditions have to remain fairly stable.

Anderson says when these lichens are found on crown land, they receive a buffer zone around them that “supposedly allows their habitat to remain fairly unchanged.”

But the “crux” of the problem, she says, is that forests are not surveyed for these rare lichens ahead of a logging operation.

The only lichen species that requires a pre-harvest survey is the endangered boreal felt lichen (BFL). The MTRI uses a “geographic habitat model” that helps lead lichen experts to the BFL by locating the habitat it likes best. When a forest company is going to cut on crown land that overlaps with the habitat model, the company is required to contract a third party who will check the harvest block for the BFL before cutting can begin.

Anderson explains that in the course of a survey for BFL, if any of the other listed lichen species are found, then they get a buffer too, “but the vast majority of crown blocks do not get surveyed [for these] ahead of harvest, because there is no mapped habitat [for them].”

When it comes to whether a 100m buffer for these species is sufficient, Anderson echoes Toms.

“We just don't know. We need long term studies. Boreal Felt lichen has been studied… But we don't really know about these three.”

Frosted glass whiskers (Sclerophora peronella). Brad Toms: “A stubble lichen, consistently found in old growth forest on the exposed core wood (scars) of red maple trees. This species is given consideration under the SMP in Nova Scotia, but is not protected under the Act. It is listed by COSEWIC. Photo: Government of Nova Scotia.

Vanishing in real time

According to Newington, the endangered mainland moose are known to frequent the Beals Brook forests. “A few softwood stands offer winter shelter” for the creatures, she says.

Alces alces americana was declared endangered in 2003. When a recovery strategy was finally drafted in 2007, recovery was actually considered “technically or biologically feasible.” But according to Bob Bancroft, who served as a member of the recovery team, “the team was unable to do one thing for one moose.”

Even with a recovery strategy in place moose are “continuing to die off because of overcutting in their habitat,” he says.

The results of an aerial survey conducted in the winters of 2017 and 2018, obtained and reported by the CBC, show a steep decline in the numbers of mainland moose from an estimate of roughly 1,000 animals in the early 2000s to fewer than 100 today.

In November of 2021—nearly two decades after moose were designated as endangered—the department announced a “new,” “evidence-based” recovery plan for the species. This time the plan identifies areas “to be considered” for designation as core habitat. Core habitat is a specific area that’s essential for recovery and long-term survival. About two-thirds of core habitat is located on crown land or protected areas.

Mainland moose concentration areas, Recovery Plan (2021), DNRR.

According to the DNRR, moose need mature forests, particularly in winter because the closed forest canopy reduces the amount of snow accumulation, making it easier for them to get around while they forage. Forest harvesting also brings road access, which creates greater disturbance of moose.

When I asked the DNRR about the Beals Brook site’s importance for moose, a spokesperson replied:

“The Beals Brook site was not identified as mainland moose core habitat, nor is it considered a wildlife corridor, and it’s not currently being considered for addition to the protected areas network. Core habitat, which focuses on highest quality habitats which will support recovery and survival of the species, was identified based on the population objectives specified in the recovery plan. Not all areas where moose may be present are core habitat.”

According to Bancroft, “The new core habitat map mostly captures the concentration areas well. An exception appears to be the Beals Brook site, and I’m certain that there are others.”

Bancroft says that while “a lot of good work” went into the new recovery plan, “the government has not changed the gross-mismanagement of core habitats for mainland moose. Core habitats are being clearcut; variable retentions of 10-50% are still clearcuts by the government’s own definition—using the old interim guidelines, which are a farce,” he says.

The way Bancroft sees it, the Beals Brook forest is too small to be considered core habitat on its own “but it could become a vital part of a much larger area that moose used to use there, and might even eventually use again if it was managed properly.”

Moose caught by a trail cam in the Beals Brook area (date stamp should be fall of 2020) Photo courtesy: Daniel Baker.

Government failures, chronic and systemic

By the time Izaak Walton Killam founded the province’s first pulp and paper mill in 1929 on the banks of the Mersey River, the forests of the province were already in decline. In fact, their “poor condition” was observed as early as 1912 when the Dean of Forestry at the University of Toronto reported they were “being annually further deteriorated by abuse and injudicious use.” B.E. Fernow warned—more than a century ago—that the forests were “liable to exhaustion,” and called on those who had the “the continued prosperity of the province at heart” to “arrest further deterioration and to begin restoration.”

But forest “exhaustion” was never much of a concern for the pulp industry. It can profit quite handsomely from the low-grade wood that comes from a forest in decline.

The province’s first official forest inventory was published in 1958 and it indicated that the downward spiral reported by Fernow had basically continued, unabated. Fernow’s dire observations were even referenced in the inventory report, which expressed alarm over the loss of larger trees and the need for industry to “accept smaller and smaller stock.”

Indeed, if you look at the province’s forest inventory data from 1958 to 2003—which I’ve done—you will see some disturbing trends in forest age diversity. Forests are getting significantly younger. The percentage of young forest up to 20 years increased by more than 300 per cent and the 21- to 40-year-old age class increased by 103 per cent. During the same time period, the old forests were disappearing: the 61- to 80-year-old age class dropped by 65 per cent; the 81- to 100-year-old age class by 93 per cent; and the 101-plus-year-old age class by 97 per cent.

Over the 45-year period, harvest volumes also increased, peaking in 1997 at roughly 70,000 ha, about 50 per cent higher than it had been 20 or 30 years earlier, and nearly all of it (98 per cent) was clearcut. But according to the National Forestry Database, since then the amount of land being harvested on an annual basis has been decreasing and in 2013 it amounted to about 29,000 ha, less than half of what it was in 1997, with 90 per cent of that still being clearcut. According to the Registry of Buyers, volumes cut have also declined, from 6.2 million cubic metres in 1999 (the first year a Registry report was published) to 3.3 million cubic metres in 2019, the most recent year for which data are available.

But one has to take what seems to be good news with a grain of salt.

First, while there appears to have been a decrease in the volumes cut, there has also been a noteworthy shift: In 1997, which was the peak year for harvest volumes, only 9% of the harvested wood came from crown land (the rest from private), compared to nearly 30% in 2017, and 25% in 2019. In other words, over the last 25 years, the share of harvest volume coming from public forests has increased.

Drone shot of a 2018 Westfor clearcut on crown land. Lake Rossignol can be seen on the top right. Photo courtesy: Jeff Purdy.

Second, the Registry of Buyers is the only source of public data on annual harvest volumes broken down by primary forest product category. A primary forest product essentially refers to what the wood is being cut and acquired for in the first place. There were 158 registered buyers in the province in 2019 and they all self-report their product purchases. This information is what’s used by the government to report annual harvest volumes, ensure sustainable harvests, and estimate a future wood supply. But the accuracy of the forest harvest data reported should be in serious doubt. In the roughly 25 years that the registry has been in place, the government has never performed an audit to verify its accuracy.

Third, reported declines in forest harvest volumes have not resulted in increased biodiversity. If anything, the opposite is true.

According to the East Coast Environmental Law Association (ECELAW), since 2015, 11 more species have been added to the “at risk” list, bringing the new total listed as endangered, threatened, or vulnerable from 52 to 63.

Over the last number of years the department has been on the receiving end of a spate of well-deserved censure:

In 2016 the province’s auditor general found that the department had been derelict in its duty to protect species at risk.

In 2018, the aforementioned Lahey Review provided further evidence of the systemic and longstanding nature of the department’s failures.

Then in the spring of 2020, a Supreme Court justice found the government failure not to abide by its own endangered species law to be chronic and systemic.4

In 2019, in what appeared to be an effort to turn over a new leaf, the government announced that in response to Lahey and the attorney general, it was setting up “new and revitalized” recovery teams for species at risk.

But by 2021 the long-awaited effort seemed a feeble one at best. In its species at risk update, the ECELAW found that the NS government had only managed to meet the fundamental requirements set out in the Endangered Species Act for 24 of the 63 species that are listed under the Act.5

Instead of actually fulfilling its legal obligation to protect species at risk, the government has busied itself with changing definitions (clearcut), purging terms (clearcut), renaming the department (twice, making it harder to find information), and, well, approving clearcuts.

In his review, Lahey exposed the dysfunctional culture that exists in the department and noted “a significant gap” between what the department says it’s doing to manage forestry on crown land and “how it’s actually managing forestry on crown land.”

In November of 2021—3 years after his landmark report—Lahey penned an evaluation of the government’s progress in implementing his recommendations.

Lahey writes:

“None of the work underway on [Forest Practices Report] recommendations has resulted in much if any actual change on the ground in how forestry is being planned, managed, or conducted, and I have no indication of when any of it will. From the information at my disposal, I am not able to conclude that much or any change has happened in how forestry is practised based on the work the Department has done on implementing the FPR. This is the overriding and central conclusion of this evaluation.

Combined with the fact that only five recommendations have been fully implemented, and that the implementation phase of work on recommendations has not started on roughly two-thirds of all recommendations, implementation cannot so far be judged a success.”6

Lahey also notes that “moving implementation of the Endangered Species Act past improving policies and procedures for its implementation on Crown to its actual implementation on the ground on Crown and private lands,” requires “urgent attention.”

I’ve said this before, and I’ll say it again: if change is happening on the ground, it’s slower than molasses in January.

Beals Brook forest in deep snow. Photo courtesy: Nina Newington.

A roadmap for resistance

Sandra Phinney is a freelance writer and photographer. She’s also a “forest protector” and has spent some time at the Camp and plans to go back. When asked what motivates her to want to be part of the protest, she replies with one word, “anger.”

“Anger that our government has not taken its responsibility to care for our Species at Risk. Anger that it's allowed the degradation of our forests which, in turn, is contributing to climate change. Anger that DNRR has become a department that kowtows to the forestry industry and is focused more on harvesting than conservation… For me, being part of trying to save our forests from clearcutting is a way that I can channel my anger and not get bitter. Mind you at age 77, sleeping in a tent in sub-zero weather is not my idea of fun. But, it's something I can do.”

Phinney has participated in other blockades to stop the clearcutting of moose habitat. In 2020, she was part of a group led by Extinction Rebellion that set up camp in Digby County, blocking logging roads for weeks until they were arrested for refusing to obey a court order to stop.

“The push is on to remove the best stands on crown lands, including what used to be magnificent old forests such as the one we tried to protect at Rocky Point. The destruction there (now) is sad beyond measure,” she says.

“The bottom line is I have three children and four grandchildren. I need to believe they will have healthy forests in their future. Their lives, and the life of our planet will depend upon it.”

Map of Last Hope Camp Protected Area Candidate. The proposed area would protect one of the last relatively intact areas of wetland and forest on the Annapolis River watershed side of the South Mountain. Photo courtesy: Nina Newington.

“The more we learn about the area and the longer we spend there, the more we know that it needs to be protected,” says Newington. “We would pack up camp if the harvest plan was cancelled or if this parcel is placed under consideration for protection.”

“This forest should be allowed to mature… Its ecological value vastly outweighs the meagre amount of merchantable lumber it will yield,” says Newington.

When I read through the seven-page “protected area” proposal prepared by Newington describing an incredibly diverse and increasingly endangered landscape, all I can think of is how this forest has become a symbol: a symbol of how our relationship with the Earth has gone off the rails and how protecting places like Beals Brook can help correct it.

Nina Newington. Photo courtesy: Sandra Phinney.

Postscript: For this article I reached out to the DNRR for clarification on the harvest rules around wetlands and marshes. According to the regulations, “marshes” are considered “watercourses” and should therefore be given a 20m buffer. This response was received after the piece went live: “Marshes are included as watercourses that are subject to a 20m special management zone. Limited harvesting is permitted in the special management zone. Regulations specify the base area of living trees must be at least 20m2 per hectare, and openings in the dominant tree canopy less than 15m, can occur within this zone.

Also, the new Silvicultural Guide to the Ecological Matrix specifies that harvesting on Crown land should not occur in sensitive forest groups, including flood plain, wet coniferous and wet deciduous forests.”

In the spring of 2021, Jonathan Porter retired from his position as executive director of the province’s renewable resources branch. After the September election, the Department of Lands and Forestry (formerly the Department of Natural Resources) became the Department of Natural Resources and Renewables. The Renewable Resources branch is now the Forestry and Wildlife branch, a change that took place following the merger between the former Lands and Forestry and Energy and Mines departments into Natural Resources and Renewables. Gerald Post is now the acting executive director.

In 2008, one (then) DNR study sampled watercourse buffers bordered by clearcuts and found that “the highest concentration of blowdown and soil exposure occurred along the clearcut edge where the trees were most exposed.” The blown down trees were uprooted the vast majority of the time (89 per cent), exposing the soil and changing the structure of the forest floor by “producing mounds and pits” and increasing “the susceptibility to soil erosion.” Soil erosion and sedimentation degrade the quality of lakes and streams, destroy the habitat of aquatic organisms and cause declines in fish populations. The DNR scientists concluded that “to maintain the highest integrity of stream side forest after a harvest…the use of a 30 m [buffer] is favourable in these conditions.”

Furthermore, in his 2018 Review of forest practices, Lahey concluded that “the adequacy of the watercourse protection provisions currently prescribed in the Wildlife Habitat and Watercourse Protection Regulations should be independently studied,” and that “the regulations should be amended in accordance with the outcomes of this study.” This doesn’t appear to have happened. In fact, in Lahey’s 2021 evaluation of the implementation of his recommendations he found that the government had yet to review the efficacy of regulations on riparian zones and that it was a matter that needed “urgent attention.”

Lahey Review, p. 5. Lahey recommended a “triad” approach to forest management that includes three elements: protected areas, high production forest areas where forests are managed like farms, and an “ecologically based matrix” where harvesting would follow ecological principles. In the “matrix” there would be a lot less clearcutting, and other forest values would be taken into consideration.

The court case was led by a group of naturalists including wildlife biologist Bob Bancroft, the Blomidon Naturalists Society, the Federation of Nova Scotia Naturalists, and the Halifax Field Naturalists, with the help of lawyer Jamie Simpson. They focused on six species they felt represented the key government shortcomings: mainland moose, Ram’s head lady slipper, Canada warbler, black ash, wood turtles, and the eastern wood pewee.

For a more in-depth discussion about forest-dependent species at risk in Nova Scotia please take a look at pages 15-23 of this report.

According to Lahey’s evaluation, progress can be summarized as follows: “Work has started on 40 of the 44 recommendations (91%); Work on 26 recommendations (59%) is in the policy and planning stage of implementation; Implementation beyond policy and planning is underway for 10 of the 44 recommendations (23%).”

Excellent overview of the forestry issues that have inspired many to support the Last Hope Wildlife Corridor. Clearly, proper protections for critical habitat are long overdue. DNRR's failure to take action based on science is something we will all live to regret.

Thanks for this detailed context of the Beal's Brook protest. The mantra is that if we "Implement Lahey" (the way NRR chooses to implement it), everything is OK. It isn't.