Nothing to Fear: The Unvested Interests of Rosalie Bertell

Part 3: ‘Scientific disinformation,’ censorship, and going ‘rogue’

When Rosalie Bertell began writing No Immediate Danger in 1976, she had already been working for seven years as a senior cancer researcher at the Roswell Park Cancer Institute in Buffalo, New York. It was there that Bertell was first introduced to the world of radiation, immersed in leukemia research. Not long after, she was also introduced to the secrecy, censorship, propaganda and manipulation that were also part of that world. This led to her becoming not only an advocate for the victims of all kinds of industrial exposures, including radiation, but an unapologetic activist.

In her book, she devoted an entire chapter to the “problem” of ionizing radiation and described what happens inside the living cell when it’s exposed to it. She quoted Karl Morgan, American health physicist who was part of the Manhattan Project and served as Director of Health Physics at Oak Ridge National Laboratory from 1944 to 1972.1

Morgan described radiation as “a madman loose in a library.”

When living cells are exposed to these “microscopic explosions and the resultant sudden influx of random energy and ionization,” Bertell wrote, they either die or are altered, permanently or temporarily. The changes could make the cell unable to replace itself.

“In time there may be millions of such altered cells… the gradual breakdown of human bio-regulatory integrity through ionizing and breakage of the DNA molecules gradually makes a person less able to tolerate environmental changes, and less able to recover from diseases or illness.”

The dangers of ionizing radiation aren’t that controversial really, at least not when it comes to high doses. The US Nuclear Regulatory Commission concedes that when ionizing radiation passes through living tissue it “deposits enough energy to break molecular bonds and displace (or remove) electrons.” These “changes in living cells” can be “potentially harmful if not used correctly, and high doses may result in severe skin or tissue damage.”

But Bertell believed that irreversible damage could also be caused by low doses, something that would eventually get her in hot water.

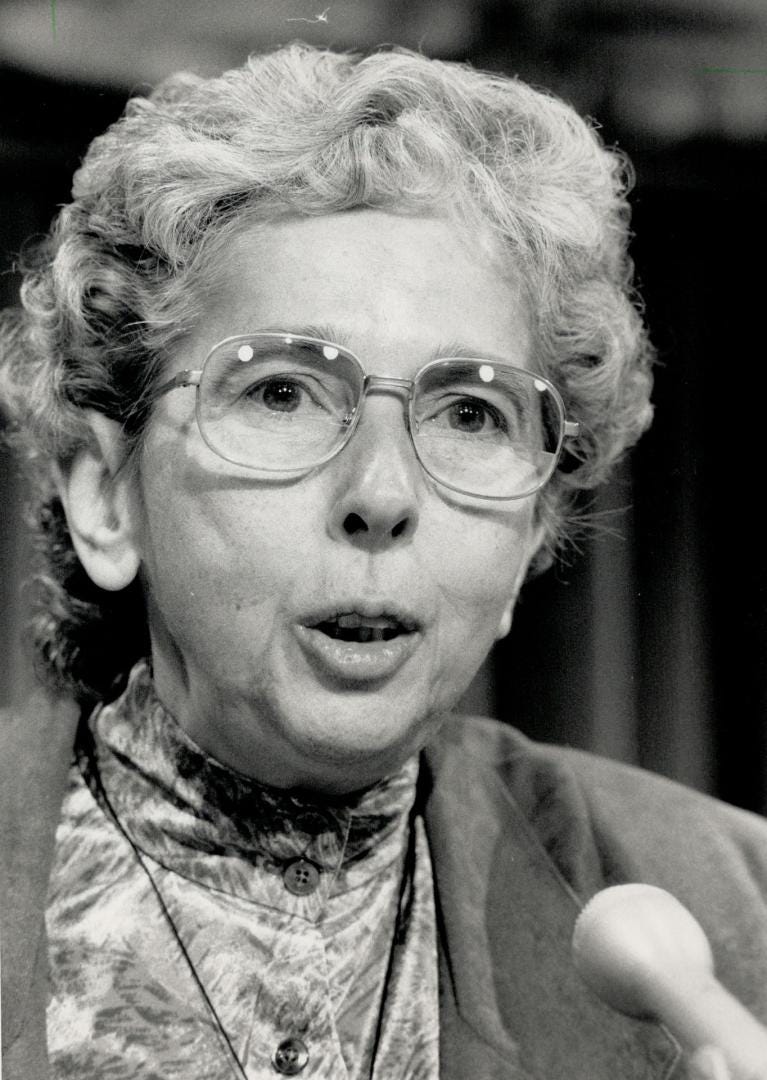

Rosalie Bertell (April 4, 1929 - June 14, 2012); Digital Archive

At the cancer institute Bertell was tasked with analyzing the “Tri-State Leukemia database”—six million people in Maryland, New York, and Minnesota were followed over a three-year period to see what would happen with respect to the incidence of leukemia, a bone marrow cancer, which had been on the rise in the northeastern United States since the 1960s.

When Bertell was hired, the study had already been collecting information about socio-economic status, occupation, health and medical history, and it was her job to assist in analyzing it.

“After examining many variables, it became obvious to me and everyone else on the team that the really strong effect, the leukemia effect, was coming from diagnostic medical x-rays,” Bertell was quoted saying in her biography. “By using x-rays we were increasing leukemia by accelerating body breakdown, aging.”

The increase in leukemia was at both ends of the age spectrum: in young children whose immune systems were not yet functioning fully, and are more vulnerable to the radiation, and the elderly. Her colleagues also found that children of mothers who had x-rays during pregnancy had an increased risk of getting the disease.

At the time, the dangers of low-dose ionizing radiation wasn’t a complete unknown. Years earlier, Dr. Alice Stewart had done ground-breaking research in the UK on the risks of obstetric x-rays to unborn children, particularly the risk of developing childhood leukemia. As early as 1951, when Stewart was investigating it, leukemia was still relatively rare, but on the rise. Stewart and her team published their preliminary findings in The Lancet in 1956 and their definitive paper in the British Medical Journal in 1958. They found that fetal x-rays doubled a child’s risk of developing cancer.

According to Mary-Louise Engels, Bertell’s biographer, Stewart’s work was “derided, attacked, or ignored by the medical and scientific establishment.”

But Stewart’s findings were later vindicated by Dr. Brian MacMahon, an epidemiologist at Harvard’s School of Public Health, who confirmed her results, finding that cancer mortality was 40% higher among children whose mothers had been x-rayed when pregnant.

When Bertell reflected back on this time, Engels writes, she said she anticipated there would be opposition from the medical profession to her conclusion that x-ray exposure was dangerous, but she did not anticipate that it would put her “on a collision course with the nuclear power lobby.”

In the 1950s, Dr. Alice Stewart did ground-breaking research on the risks of obstetric x-rays to unborn children, particularly the risk of developing childhood leukemia. She was vilified, but later vindicated.

As previously stated in Part 1 of this series, using nuclear fission to produce electricity presented an acceptable use of the technology—generating “clean, safe, and cheap power.” Indeed, proponents of nuclear power often compared radiation exposures from these plants as being no more serious than a few x-rays. But as the Tri-State survey and work of other scientists were showing, a few x-rays might not be as harmless as everyone thought.

Bertell started sharing her findings from the Tri-State survey at meetings about nuclear power plants. Her research at the Roswell Park Cancer Institute was publicly funded after all, and so she believed the public had a right to know about it.

Then came a big win for Bertell, one that would eventually lead to her placement outside the “system.” In 1974 she helped to stop the construction of a nuclear power facility in Barker, New York. At a forum organized by the utility company, she told the audience about Dr. Gerald Drake, of Michigan, who noticed a rise in cancers after the Big Rock power plant went in. Bertell also noted that the farms for Gerber’s baby food were next to the proposed power plant.

It was never built.

But this got her in hot water with the higher-ups at Roswell Park Cancer Institute. According to Engels, Bertell began to receive “criticism and censorship,” and was warned about taking a public stand on issues involving radiation.

In her biography, Bertell recounts how she was called in by the hospital directors and “grilled” about her public appearances, particularly those on local television. “They were really uptight, especially the assistant director who spoke about how terrible it was to create trouble in the local community and speak in the name of the hospital,” recounted Bertell. “When he finished, I asked him if he was trying to tell me that when I do research at the public expense, and then go to a public meeting, I shouldn’t tell the public what I’ve found out. This question so frustrated him that he walked out of the room and slammed the door.”

Engels writes that episodes like this one “highlighted what many of Rosalie’s future critics would learn. Despite a quiet and unassuming manner, she was an intrepid opponent, skilled at enlisting support, resourceful in verbal exchange.”

At the time, the exchange with the hospital and with the nuclear power industry in general, made Bertell “uneasy,” writes Engels.

Her very public opposition to the nuclear industry is also what likely got her nearly killed on that day in 1979—as mentioned in Part 1 of this series.

“They were working too hard to keep me quiet,” Bertell recounted in her biography.

It was when Bertell got push back from the cancer hospital that she began to wonder about how and by whom permissible dose levels for radiation got determined. She traced the standards back to the US military experience in Nagasaki and Hiroshima, Japan, where two atomic bombs were dropped within days of each other in 1945. The effects of the bombs were collected by the Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission (later renamed the Radiation Effects Research Foundation or RERF), and the US government has tightly controlled the information ever since. According to Bertell, the database has only been available to a small number of approved scientists and regulators, and not to the broader scientific community.

“The atmosphere of secrecy and misinformation hobbled the scientific understanding and public awareness for decades,” writes Engels. “From the start the radiation debate was politicized.”

Thus, the standards set up by the International Commission on Radiation Protection (ICRP)—mentioned in Part 2 of this series—were based on the RERF studies of Japanese survivor populations. Bertell disagreed with the ICRP assumption that if you control the dose of radiation and spread it over time, risk is negligible. She also disagreed with the ICRP argument that risk had to be balanced against the benefits of nuclear technology. Bertell believed that if members of the public were being forced to incur a health risk, then they should also have a voice in the matter.

But the ICRP—like so many other government regulators—was captured. It was a “self-perpetuating committee right out of the military,” Bertell recounted in her biography. “A closed club, not a body of independent scientific experts.”

Even aforementioned health physicist Karl Morgan—a founding member of the ICRP and part of the Manhattan Project—conceded it was influenced by special interest groups and was rife with conflicts of interest. “I’m not sure it’s an organization I would trust with my life,” he was quoted saying.2

The Tri-State Leukemia Survey was published in 1977. In 1978, Bertell’s “extracurricular nuclear activism” and public involvement in the growing anti-nuclear movement put her on a collision course with her superiors at Roswell Park. In 1978 the institute cut her funding and she was forced to abandon her radiation research project.3

Bertell:

I thought at first that I would be challenging the medical profession, and then I thought that I was taking on the nuclear power industry – but every time I tried to resolve the problem, I ended up back at the weapons industry.

Estimated Global Nuclear Warhead Inventories, 2024 (Federation of American Scientists)

In 1985—when Bertell was Director of Research at the International Institute of Concern for Public Health in Toronto (a time we’ll explore further later in this series) she was becoming increasingly aware of the prevalence of suppression and censorship in the field of science.

In that year she penned a piece in the journal Index on Censorship in which she reported on a court case in the US involving four plaintiffs (two of them widows of cancer victims and two survivors of cancer)—former employees of the Aircraft Instrument and Development (AID) Company—who brought a suit against that company as well as 23 other companies and the US government. In a nutshell, AID had purchased instruments with radium-painted dials at salvage for reconditioning from the US government, and the 23 companies had manufactured and marketed the radioactive instruments without any warning signs. In the end, the companies decided to settle out of court, awarding the four plaintiffs $400,000 each, but the feds refused to settle out of court and according to Bertell, “launched a vigorous case.” In 1984 Judge Patrick Kelly ruled against the plaintiffs, and for the government.

The “extraordinary aspect of this ruling,” wrote Bertell—and one that we’ve seen played over and over again in the field of science since—was how the case was used to vilify three expert witnesses called to testify for the workers. The judge in the case made “derogatory remarks” essentially calling one expert witness for the plaintiffs a “laughing stock,” while referring to the government’s expert witnesses as “wholly objective, honest, and reliable.” Bertell and others were astonished by what she called the judge’s “unrestrained character defamation,” as well as his dismissal of previous court rulings where radiation injury settlements were awarded.

For Bertell, the “extraordinary personal attack on three highly credentialed US scientists” called her to conduct a “serious study of its motivation,” which, as it turned out, wasn’t too hard to locate.

Right there in Justice Kelly’s written opinion it stated: “the plaintiff’s claims are simply secondary to the interest of the United States.”

And what are these national interests, exactly?

According to Bertell:

“[They] are namely to convince people (however wrongly) that exposure to low level radiation causes no harm. Thus the American people will be willing to handle uranium, run the nuclear reactors, separate out the plutonium, fabricate and test the bombs, and tolerate the radioactive debris left from each part of the weapon cycle. The victims of this deception must be ignored because of the greater ‘good’ of national security in a nuclear age.”

Bertell was alarmed that the government “justified lying” and the spreading of what she called “scientific disinformation,” for national security purposes.

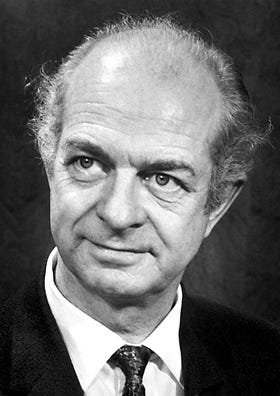

Linus Carl Pauling, February 28, 1901 – August 18, 1994

According to her biography, Bertell’s concerns about the dangers of low-level radiation were characterized by opponents in the nuclear industry as “exaggerated” and “hysterical,” and she eventually lost her standing in the field of cancer research. But she was not alone. In fact, there were many others who challenged the official nuclear industry narrative who lost their reputations, funding and even their livelihoods.

For instance:

Dr. Edward Weiss who connected extraordinarily high rates of leukemia and thyroid cancers in Utah in the 1960s, to radiation fallout from the Nevada Test Site, lost his federal funding.

Dr. John Gofman was a highly respected nuclear chemist who was also part of the Manhattan Project indirectly by discovering how to separate plutonium from uranium. Later, as director of the Atomic Energy Commission’s laboratory in California, he concluded there was no safe threshold of radiation. In 1969, he and a colleague Dr. Authur Tamplin estimated the cancer risk from radiation was 20 times higher than what they were being told. His staff and budget were slashed and he and Tamplin resigned, and penned the book Poison Power in 1971, outlining the dangers of nuclear energy and radiation.

Linus Pauling, winner of the 1954 Nobel Prize in chemistry, also lost his academic standing when he warned that weapons testing would cause millions of birth defects, embryonic and neonatal deaths, and cancers. He was outspoken and sent letters to government officials in the US and USSR as well as to scientists around the world, calling on them to halt nuclear weapons testing. According to Engels, Pauling’s petition with more than 11,000 signatures persuaded the US and USSR to agree to a moratorium on above-ground nuclear testing in 1963. But nevertheless, Pauling became an “outcast” at the California Institute of Technology, and eventually resigned.

“He was one of the first scientists to lose his academic mooring after opposing the ‘official line,’” writes Engels.

So, Bertell was in good company. But like so many other talented and brilliant scientists, there were expectations on Bertell to toe the line, right from the beginning.

Before her stint as a cancer researcher, Bertell was tapped in 1963 by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) for her mathematical prowess and offered a grant to earn her PhD in mathematics. She taught for ten years at the D’Youville College, and, rather surprisingly, also did basic research on guided missile systems in the engineering department of Bell Aircraft. Between 1967-1968 she reviewed environmental impact statements for the US Department of Energy.4

Bertell saw first-hand how young, intelligent students were “captured by the secret military projects into which money and resources are poured.” She called it a “brain drain” which had “the effect of harming all civilian enterprises, including medical and educational services.” Bertell argued that because funding was often contingent on the project having “some area in which there is a military interest, it biases the economic and the intellectual efforts of society toward military priorities.”5

As Elizabeth May put it, “Rosalie had the incredible history of having been part of the military industrial complex and quitting that out of conviction.”

Later in this series we’ll return to Bertell’s early background, which gave her a particular insight into the subject matter in her last book, Planet Earth: The Latest Weapon of War.

[Stay tuned for Part 4, which will explore Bertell’s Toronto years heading up the International Institute of Concern for Public Health, where her life was again threatened.]

I also want to mark that tomorrow, on January 10th, the Quaking Swamp Journal officially turns 3! There are currently more than 100 articles in the archive! Thank you for supporting independent journalism and my commitment to never stop asking legitimate questions in the public interest.

For a Canadian angle to the Manhattan Project story, I would highly recommend the 2008 National Film Board of Canada documentary collection, The Strangest Dream, produced by Kent Martin. It tells the story of Joseph Rotblat, whose “conscience would not allow him to continue, and he became the only member of the Manhattan Project to leave on moral grounds.” The film also looks at “the history of nuclear weapons, and the efforts of the Pugwash Conferences on Science and World Affairs - an international movement Rotblat co-founded - to halt nuclear proliferation.”

Dr. Karl Morgan quote taken from Engels, Mary-Louise (2005), Rosalie Bertell: Scientist, Eco-feminist, Visionary, p. 51.

For more on the tyranny of the nuclear industry and Rosalie Bertell: https://www.thesunmagazine.org/articles/25400-the-new-nuclear-tyranny

From Bertell’s book Planet Earth: The Latest Weapon of War, p. 255.

Bertell quotes taken from Engels, pp. 20-21.