Access to Information reveals lack of transparency in amendments made to Recovery Strategy for Atlantic whitefish

More than 1,200 pages of documents obtained through an Access to Information request (ATIP) reveal that the 2006 published version of the Recovery Strategy for Atlantic whitefish was cleansed of references to logging, soil erosion, siltation, and the productivity and quality of aquatic ecosystems before it was circulated in a consultation process, calling the transparency of the process into question.

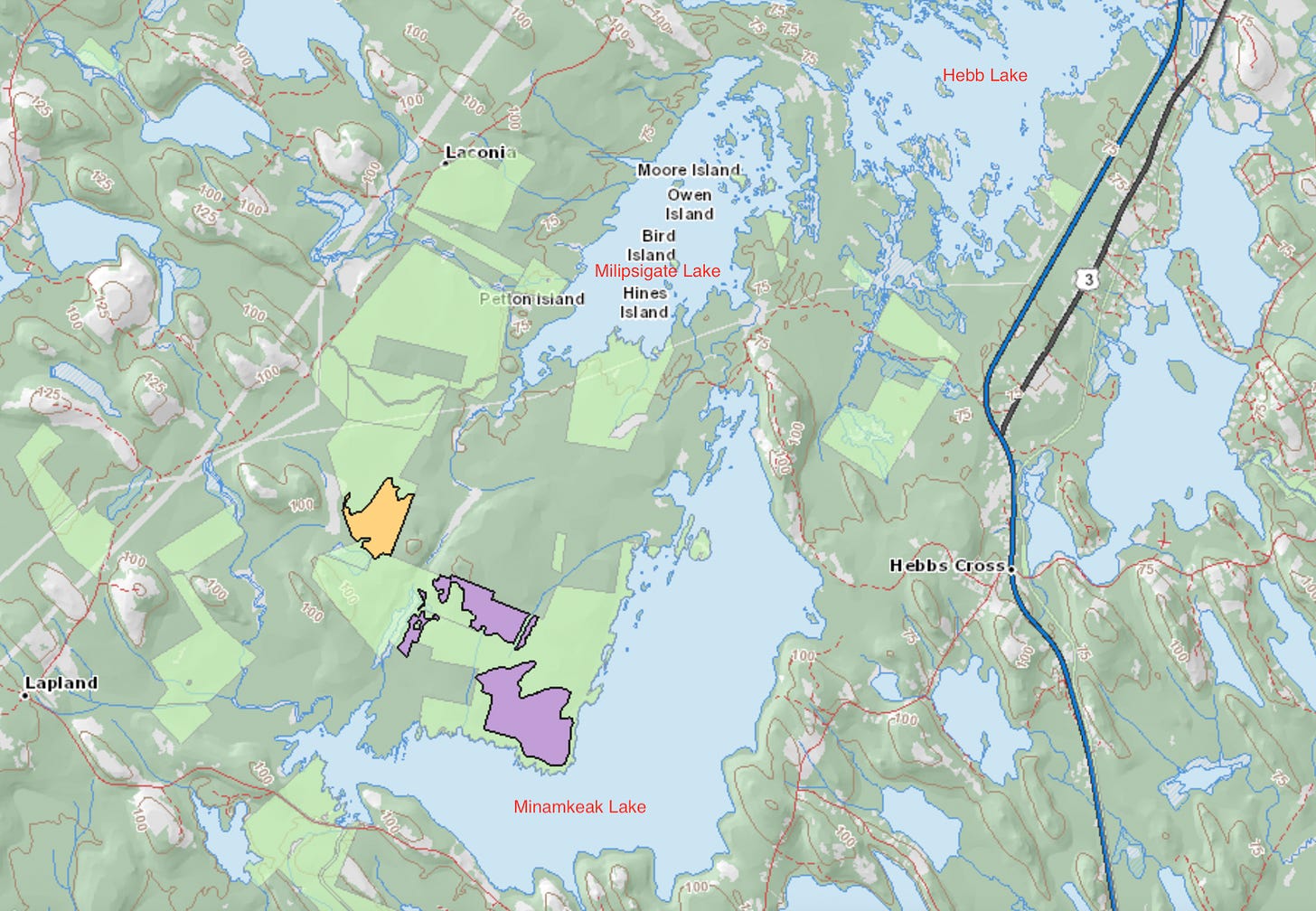

Recall, in March of this year, the Nova Scotia Department of Natural Resources and Renewables (DNRR) posted 103 hectares of forest land on the Harvest Plans Map Viewer—crown land that falls within the protective watershed of Minamkeak Lake, one in an interconnected system of three lakes that are home to the last surviving wild population of endangered Atlantic whitefish.

Faced with a deluge of opposition to the proposed logging plans, the DNRR announced in early May that it was placing an “indefinite hold” on the proposed logging plan, stating, “The primary concern is potential impact to the lakes, where the endangered [fish] are located, due to road construction needed to access the proposed harvest area.”1

The Quaking Swamp Journal covered the story in a series titled, The Atlantic Whitefish Whitewash— part 1, part 2, part 3. As was laid out in the series, important references to the detrimental effects of logging on fish that were present in the original version of the Recovery Strategy—published in December 2006—were missing from the “amended” version, published in 2018, and “adopted” in 2021.

In other words, in the most recent version of the Recovery Strategy, references to the effects of logging on water quality and therefore the recovery of the already beleaguered species were nowhere to be found.

Atlantic whitefish, DFO

Specifically, the 2006 version made reference to forestry as being a “threat” or “limiting factor” for the species and made particular note of how the species was extirpated from the Tusket River system where the “most significant threats” included “over-harvesting.” The original version also included a detailed section on “land use practices,” and it referenced logging, stating it can “cause accelerated soil erosion and siltation that can lead to a reduction in the productivity of the aquatic ecosystem and affect the rate and quality of water runoff.” It also referenced two important unpublished studies, which The Quaking Swamp Journal located and reported on here, that found logging could have “severe implications for surface water quality" and the "effect on migratory fish may be permanent."

The question is, why were these references removed?

These were the proposed harvest blocks in the Petite Riviere watershed, totalling 103 ha. The DNRR has since placed an “indefinite hold” on the plan. Screenshot taken from Harvest Plans Map Viewer, DNRR.

As previously reported in Part 2 of the series, I reached out to Kim Robichaud-LeBlanc, the lead recovery biologist with the Species at Risk Program of the Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO) for the Maritimes Region to find out what happened to the logging references. Through a DFO media relations person, Robichaud-LeBlanc said that a consultation period took place after the 2006 version was published and that the final “amended” version required consideration of all the comments received during the public comment period. After the comments were taken into consideration, revising the “threats” section of the Recovery Strategy for Atlantic whitefish included “restructuring the section on threats to better separate past and current threats, and updating it to include new information.”

At the time, I understood this to mean that the sections in question were restructured as a result of input received from various players during an official review process, so I filed an ATIP request (following DFO’s advice) to obtain the consultation records. I wanted to know if forest industry players, or the DNRR acting on behalf of the forest industry put pressure on the DFO, during the consultation process, to remove any connections between logging, water quality, and the viability of Atlantic whitefish.

But instead, what I discovered is the changes did not take place as a result of the consultation/ review period, as I was led (intentionally or not) to believe. Instead, the changes were made before the recovery strategy was sent out for review.

Image taken from the 2001 (adopted) Recovery Strategy for Atlantic Whitefish

While my ATIP request asked for feedback, letters, or comments from individuals, industry, or government with respect to the recovery strategy dating from 2007 to 2018, what I received back were comments and edits relating to a “2011 draft” and a “2012 draft" of the recovery strategy. However—and this is the key point—the logging references that were present in the 2006 version were not present in the “2011 draft,” indicating the document being circulated for comment had undergone significant changes beforehand.

There was no record provided indicating why the sections in question had disappeared.

According to the ATIP documents, in October 2011 Robichaud-LeBlanc circulated two, already amended documents—the recovery strategy, and a draft action plan—to Species at Risk (SARA) Planning Committee members. She writes:

These versions of the documents are the result of extensive working level development and review by SARMD [Species at Risk Management Division] staff in close collaboration with relevant DFO sector representatives in the Region (principally Greg Stevens in FAM, Rod Bradford in Science and Jennifer Giorno/ Melanie MacLean in HPSD) and in broad communication with the Atlantic Whitefish Conservation and Recovery Team and is now ready for review by this committee.2

This statement indicates that DFO staff and others had been making amendments to the recovery strategy prior to the consultation process. Indeed, the ATIP documents reveal that the section on “threats” in the “amended” version that was being circulated for comment and review was already significantly restructured, and missing the aforementioned references to logging-effects present in the original 2006 version.

According to the “amended” 2011 version, the section under “threats and limiting factors” was “reviewed” during a DFO Regional Science Advisory Process meeting in 2009 and that the advisory process “consolidated new information on Atlantic whitefish and provided up-to-date information and advice on the relative level of impact of described human activities on the species and possible alternatives and management measures to mitigate these impacts.”

I turned to the 2009 Proceedings to see if there was any indication of a discussion about removing forestry operations as a threat to the species. But the official record of the two-day meeting held at the Days Inn in Dartmouth came up empty. There was no mention of forestry practices, let alone how logging has in the past, and could in the future affect water quality and Atlantic whitefish habitat.3

The ATIP documents also show that in 2013, Robichaud-Leblanc sent out a second draft of the documents to the Atlantic whitefish recovery team members. She also launched a “jurisdictional review and external comment period” and contacted relevant NS government departments, First Nations groups, and the Public Service Commission of Bridgewater.

In response, on May 6, 2013, the Deputy Minister of the DNRR (formerly the Department of Natural Resources) sent a letter to Faith Scattolon, the Regional Director-General of DFO regarding the recovery plan for Atlantic whitefish. Duff Montgomerie wrote (in part):

Our province’s involvement with this species goes back many years. We were involved in formation of the recovery team and in developing the initial recovery strategy. While we support DFO’s initiative in moving the action plan forward, we disagree with some of the weighting of priorities and approaches to effecting recovery. These issues have been raised with DFO before and remain largely unaddressed in the action plan.

The letter does not provide any details regarding what the DNRR disagrees with, but it’s clear that “issues have been raised with DFO before.”

Could these issues relate to the need to downplay the role logging activity could have on water quality? We know the DNRR did not participate in the 2009 Proceedings. It also did not provide comments to the DFO regarding the draft 2011 or 2012 recovery strategy. Question is, did it communicate these “issues”—and manage to influence the amendments made in the recovery strategy—in some less transparent way?

Atlantic Whitefish, Courtesy Ian Manning (Wikimedia)

Also worth noting is that in response to the call for comment, in February 2013, the deputy minister for the NS Department of Environment, Sara Jane Snook, wrote to Robichaud-LeBlanc to establish that the NSE was in support of the watershed becoming a Wilderness Area.

Wilderness Area or other protected areas designation may be complementary to the efforts of the Recovery Strategy, providing increased protection for the watershed and surrounding ecosystems. Protected areas designation can also be complementary to the protection of drinking water supply areas; several examples exist within the province.

You may be aware that the area proposed as critical habitat overlaps with the Bridgewater Protected Water Area. As a Protected Water Area under the Environment Act, the water utility is able to regulate activities that may impair water quality within the source water area. There may be overlapping interests and I encourage the Recovery Team to work with the water utility to ensure water quality within this area is maintained.

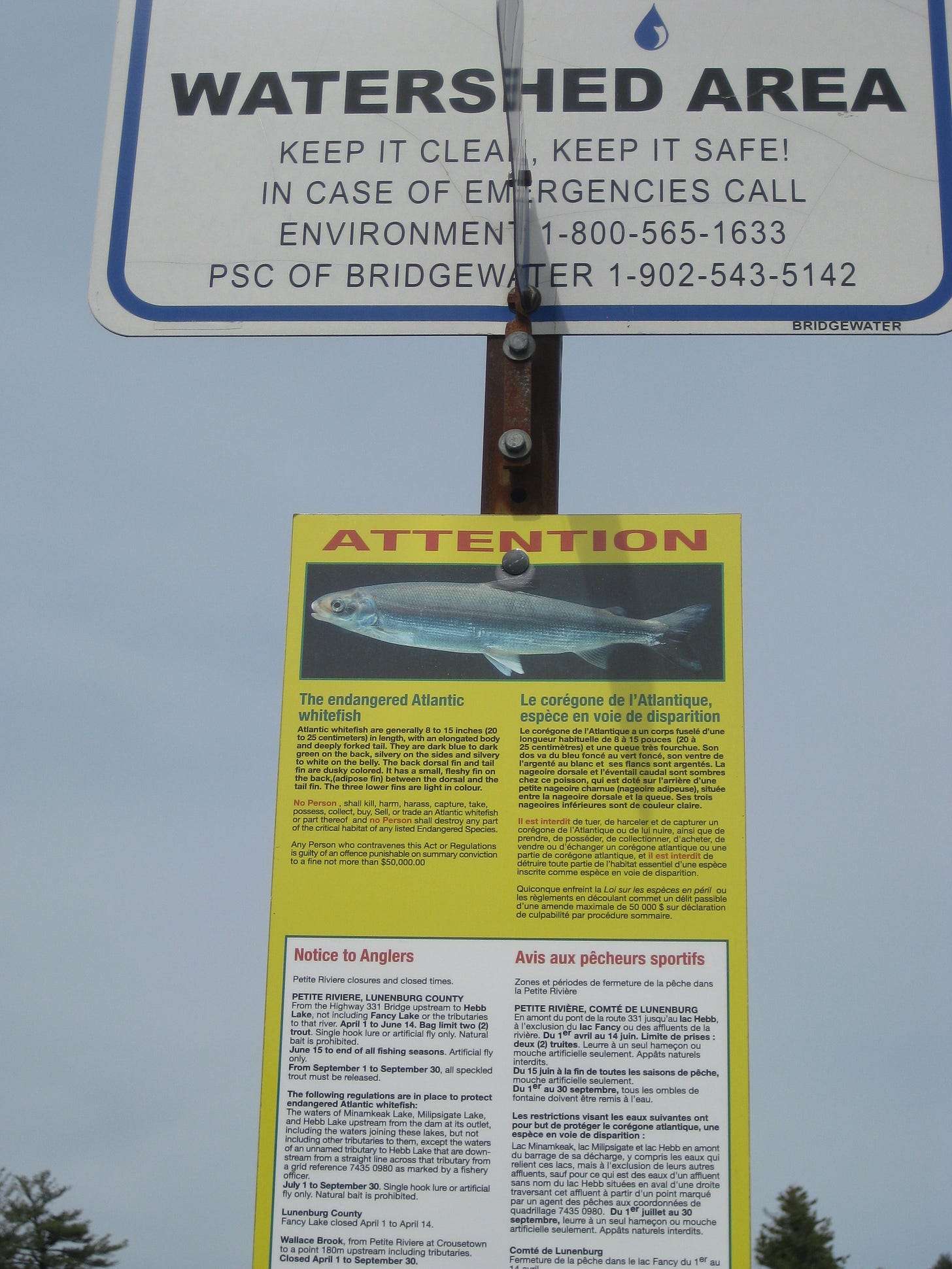

Sign posted on the shore of Minamkeak Lake. Photo: Linda Pannozzo.

Realizing there is no record within the ATIP documents of when the logging-effects references were deleted, or who was responsible, I sent a follow-up email to DFO’s ATIP analyst, Caitlin de Savigny asking her to include the records for the time period leading up to the “2012 draft.”

Specifically, I said I want to know why the water quality science, as well as two unpublished studies specific to the Petite Riviere watershed—that both point to the damage logging can have on fish—were not included in the “2011 draft."4

In response, de Savigny writes: “I will need to return to our subject matter experts in the region and ask these questions to them. I will respond as soon as I am able.”

Stay tuned for de Savigny’s response. We will eventually get to the (murky) bottom of this.

There was a joint call by a number of organizations as well as the NS Department of Environment, for the public lands around the three lakes to be designated “Wilderness Area.” The groups included Coastal Action, Healthy Forest Coalition, Bridgewater Watershed Protection Alliance, Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society (NS Chapter), Dalhousie University, and the Bridgewater Public Service Commission.

Greg Stevens is with DFO’s Fisheries and Aquaculture Management (FAM) division; Rod Bradford is with DFO’s Population Ecology division; and Jennifer Giorno and Melanie MacLean are with the Habitat Protection and Sustainable Development division.

No one from the Department of Natural Resources, as it was known at the time, was present at the 2009 meeting. The only NS government representative at the meeting was Anthony Heggelin from the Department of Fisheries and Aquaculture.

Here are the two unpublished studies, that were referenced in the original recovery strategy (both of which I have copies of), but were missing from the “2011 draft” that the DFO circulated for review: 1) “Llewellyn, N., C. Mosher and N. Joseph. 2000. Historical and current land use study of the Petite Rivière watershed above Hebb Lake dam. Unpublished manuscript prepared for the Bridgewater Public Service Commission. October 2000. 45p.” 2) 1999 Master’s thesis by St. Mary’s University graduate student Saide Sayah titled: “A cumulative effect assessment of the Petite Riviere Watershed.”