Broken Record

Senate Committee study about effects of seal populations on fisheries recommends expanded seal harvest despite admission there is little evidence to support it

On May 23rd the Standing Senate Committee on Fisheries and Oceans released its report, “Sealing the Future: A Call to Action,” the result of more than a year of witness testimony, to determine the effects of seal populations on the fisheries on all of Canada’s coasts—Pacific, Arctic, and Atlantic. Despite the fact that the report explicitly states that the committee “was not able to come to a firm conclusion about this impact at this time,” it lays out a series of recommendations that suggest seals are to blame for fisheries declines and recommends the government “immediately take steps” to increase the seal harvest, and “ensure that commercial sealing is economically viable for harvesters.”

In fact, even though the report summarizes the testimony of experts who do know a lot about seal-cod interactions, and say that the unknowns far outweigh the knowns when it comes to what, when and where seals consume fish, the Senate recommendations do not reflect this uncertainty but instead lay out a set of urgent actions re: seals, including killing more of them.

Don Bowen’s written submission, for instance, which was quoted in the study stated, “It is doubtful that additional studies on seals or fish will yield model results that constitute a eureka moment whereby all will become clear as to the impact of seals on fish stocks of interest.” The retired Fisheries and Oceans scientist who has been studying the population dynamics of grey seals on Sable Island for nearly four decades goes on to say that to “justify a large-scale and long-term reduction of seal populations, there needs to be reasonable evidence that fewer seals would result in more fish,” evidence that he says currently does not exist.

The committee also said there was an “urgent need to develop a better understanding of the role seals play within the various ecosystems they inhabit,” and that DFO “must therefore expand its seal science program as soon as possible.”

The problem with this approach is that it seems they might be putting the cart in front of the horse. There’s little evidence to support devoting this much attention to the seals, and yet, if the “seal hypothesis” is the one receiving the lion’s share of the funding, then there will naturally be more evidence supporting it, as opposed to other equally, if not more viable, hypotheses.

As University of British Columbia fisheries scientist Daniel Pauly once told me:

“The DFO are trying to protect industrial fishing interests—policy that comes from the top down. It trickles down gently and when it reaches the people on the ground there is no scientific distortion really – you just don’t get money or funding for studying this, but you get money for studying that. This is how you can distort findings without ever being caught.”

Grey seals on Sable Island. Photo courtesy Zoe Lucas.

Senate pointed to ‘disinformation’ from animal welfare groups, but not from fishing industry

Currently, there are 30 countries that have issued import bans on commercial seal products, including all of the European Union, the US, Mexico, and India. The EU banned importation and sale of seal products in 2009, with the exception of those resulting from traditional hunts by Indigenous communities, though Indigenous groups told the committee that the “Indigenous Exemption” does not seem to be enabling their sale of seal products.

The Senate report argues that these bans were “primarily due to historical concerns” about animal welfare “that are no longer valid because of improved management practices and regulations.”

At present, Canada’s biggest seal product export markets are Japan, Hong Kong, Vietnam, South Korea, and Norway.

The fact there is little if any market for harp and grey seal products is reflected in the very low percentage “harvested” every year from the total allowable catch (TAC), set by the DFO. Between 2018 and 2022, only 1% of the TAC was landed for the grey seal “harvest” and only 7% of the TAC was landed for the harp seal.

The committee concluded that DFO was “not managing seal populations or the Canadian seal harvest,” and basically demanded it do so. It also goes on to recommend that the feds, in collaboration with key stakeholders, “create and disseminate an effective anti-misinformation / anti-disinformation campaign related to the Canadian seal harvest and seal products industry.” It also recommends that the Income Tax Act be amended to ensure that “registered Canadian charities and non-profit organizations (ie. animal welfare groups) that produce or promote misinformation and/ or disinformation about the seal harvest or seal products industry have their tax-exempt status revoked.”1

The committee pointed to several claims made—presumably by animal welfare groups in the past though no explicit sources of the information were actually given—they felt qualified as examples of misinformation and disinformation about Canada’s seal harvest including that “Canada harvests baby seals (i.e whitecoats and bluebacks). Again, without actually seeing the reference, it’s hard to know whether the offending group said “baby seals” or actually said “whitecoat and blueback.” Yes, it’s true that killing a harp or grey seal pup (whitecoat) and hooded seal pup (blueback) has been prohibited since 1987, this basically just means they can’t be killed during their first month or so of life. But when they shed their birth coat they’re fair game.

Another source of mis- or disinformation highlighted in the Senate report was that Canada’s “seal harvest is inhumane.”

I think the ethics of killing seals is highly debatable, and the debate should not be suppressed just because the fishing industry or the government who made the regulations happens to hold a different view.

Not surprisingly, there is no mention made in the report about the disinformation produced by the fishing/ sealing industry or the unions that represent them. I reported on one such anti-seal “awareness campaign” launched in early 2022 by the Fish, Food & Allied Workers Union (FFAW-Unifor) which aimed to “call attention to seal overpopulation in Atlantic Canada and the devastating effects on fish stocks.”

As part of the campaign, FFAW-Unifor produced a video that makes an astonishing claim—one that is nothing short of disinformation: “And the truth is this: fish harvesters are not ravaging our fishery, and destroying our ocean ecosystem, seals are.”

In numerous pieces I’ve written on this Substack I’ve highlighted that the problem with allowing the government or vested interests to label something disinformation or misinformation is that they themselves can be the biggest purveyors of the stuff.

Dead seals with whitecoat pup in foreground, Hay Island, Nova Scotia, 2008. Photo courtesy Rebecca Aldworth / Humane Society International. [Note: While the 1987 prohibition on killing whitecoats seems to have spared this nursing pup, killing its mother will likely have the same result. If that is not inhumane I don’t know what is.]

Science should be free from political constraint

My 2013 book, The Devil and the Deep Blue Sea – An Investigation into the Scapegoating of Canada’s Grey Seal, took an in-depth look at what could be behind the vilification of the grey seal. Around that time, the DFO were proposing a massive cull of 220,000 of the creatures involving feller bunchers and mobile crematoriums on Sable Island—the largest grey seal colony in the world. The macabre plan—revealed in a trove of documents I accessed through FOI—never happened, but it feels like those behind it will never give up trying to convince us all that a cull is necessary to save the cod.

The book also explored what other hypotheses existed for the non-recovery of the cod – one’s we continue to not hear anything about in the mainstream press.

During my research for the book, I had the honour of interviewing the late Jeffrey Hutchings, whose career was nothing short of astonishing, starting out at the DFO and then becoming a Dalhousie University professor and author of more than 250 peer-reviewed studies. Hutchings played an important role in the aftermath of the groundfish collapse – what he described to me as “the greatest numerical loss of a vertebrate in Canada’s history... equivalent in weight to that of 27 million humans.”

The long-term consequences of fishing out this much biomass from the oceans were, at that point in time, unknown. It was kind of unprecedented. But research that has taken place since, indicates that the loss may have shifted the entire biological structure of the marine ecosystem and scientists are still trying to understand the fallout.

After the collapse, there was one hypothesis that gained traction – and has never disappeared – that Hutchings referred to as a “scientifically tenuous one.” It was that the harp seals and environmental factors – and not overfishing in the fishery management areas near Newfoundland – that were to blame for the collapse.

Five years after the collapse of the groundfish, in 1997, Hutchings tackled these tenuous hypotheses head on in research he conducted with the late Ransom Myers. The study did not detect the effect of seals – which is what Ottawa wanted them to find – so according to Hutchings, it was suppressed. As I’ve previously written:

Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO) messaging at the time was that seals were implicated in the collapse of the cod, but since Hutchings and his co-authors did not come to this conclusion, they were not allowed to present their paper at an international symposium on the subject—though an oral presentation was finally permitted. As well, the DFO withheld the manuscript from being published in leading journals. In a 1997 testimony to the House of Commons Standing Committee on Fisheries and Oceans, Ransom Myers said, “They censored the paper and then they denied the paper existed.

Myers was reprimanded by senior bureaucrats at the DFO and shortly thereafter left and joined Hutchings to pursue an academic career at Dalhousie University.

Hutchings argued that if science is supported by taxes it should be free from political constraint.

“What are the personal and institutional costs of having political and other vested interests supersede, or be perceived to supersede, scientific integrity?” he asked.

Grey seals on sand dunes, Sable Island. Photo courtesy Zoe Lucas.

Seals could actually be helping cod

My book on the complex seal/ cod relationship explored some of the never-mentioned hypotheses about why the cod have failed to recover. The research for the book began with a series of articles I wrote between 2010 and 2012 for The Coast. One of the articles, which I co-wrote with Bruce Wark, became the basis for the book, and recounts a 2007 hearing at the Nova Scotia Legislature. The Hearing was being held because the province had opened up Hay Island, a wilderness area, to commercial sealing. Furthermore, the government proposed to change the Wilderness Areas Protection Act to accommodate it, arguing that the grey seals were harming the biodiversity by eating too many fish, and stunting the recovery of the cod—a species that had been brought to its knees two decades earlier because of overfishing.

In his testimony, Dalhousie marine biologist Boris Worm stood up and provided an astonishing counter-narrative. He pointed to increases in the numbers of small pelagic fish which eat the larvae and eggs of cod and concluded that because seals feed on pelagic fish “seals today are actually not hindering the recovery of cod, but actually are good for the recovery of cod.”

It certainly peaked my interest.

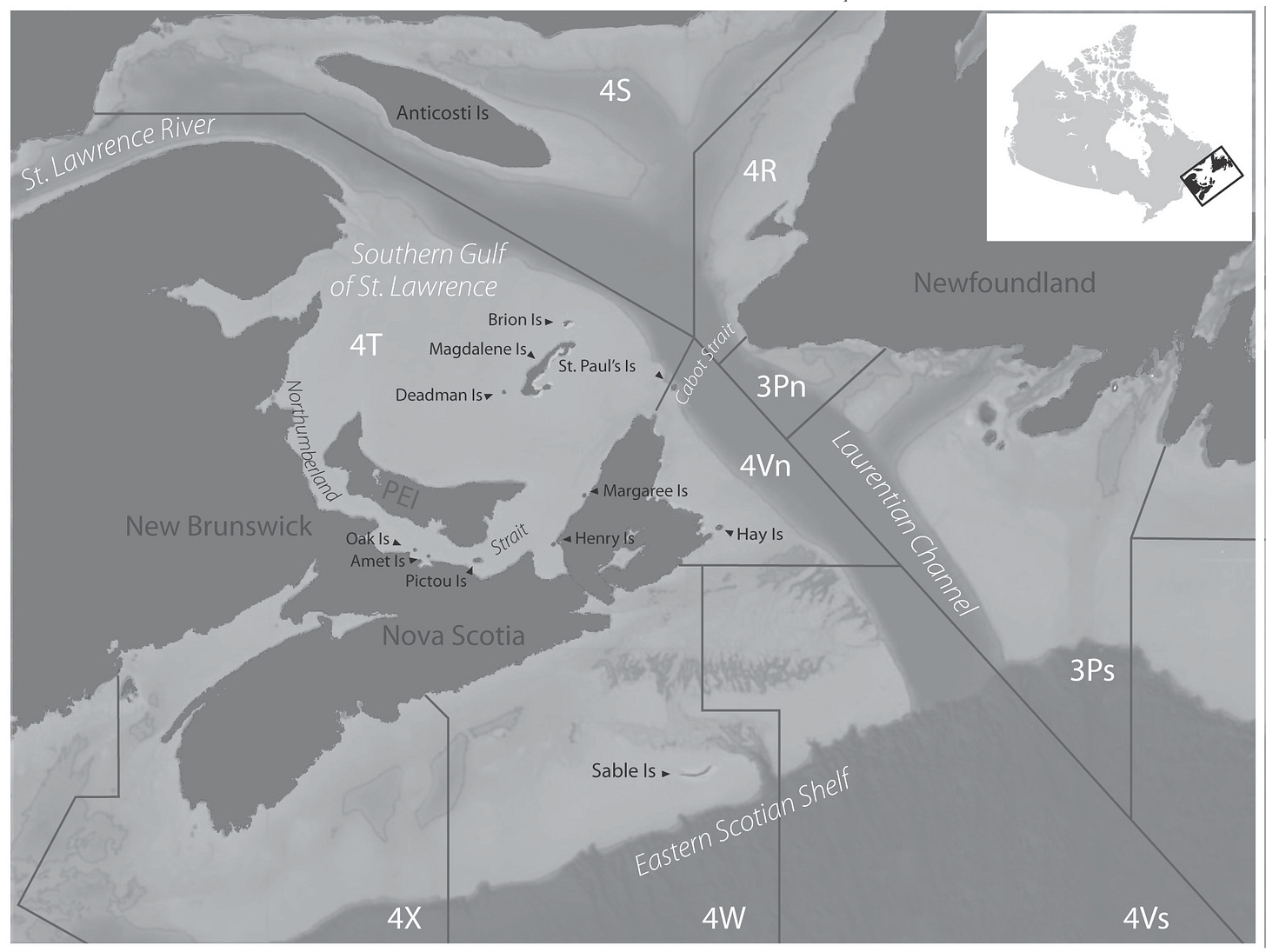

When I asked Hutchings about this, he had a slightly different take on whether seals were interfering with the recovery. He said it depended on the size and the location of the remaining stocks. In the southern Gulf of St. Lawrence, the cod stocks were teetering on the edge of extinction. “Even if you remove all the seals on Sable Island,” Hutchings said to me at the time, “it would have a negligible impact on cod on the Scotian Shelf and maybe some impact on the recovery in the Southern Gulf of St. Lawrence.”

Hutchings pointed to other factors, like fishing practices. While the fishery for cod is currently limited, bycatch of cod may not be. Numerous studies have shown that the vast majority of fisheries bycatch is discarded, either dead or in poor condition.

At that same 2007 hearing in the NS legislature, where Boris Worm spoke about the complexity of the marine food web, Liberal fisheries critic, Harold (Junior) Theriault shone a bit of a light on the bycatch problem. In fact, he complained about the illegal dumping of cod bycatch:

[On George’s Bank] there’s hundreds of tonnes of codfish going over the side, dead, not being reported, because they can’t report it, they can’t bring it in, they can’t dump it, so they can’t report it even being dumped.

Grey seal pups, Hay Island, Nova Scotia. Photo courtesy Rebecca Aldworth

Media play a role in perpetuating the official narrative about seals

On May 28th, about five days after the Senate report was released, Paul Withers of the CBC reported that “the downward spiral for Atlantic cod continues in the Gulf of St. Lawrence,” and, quoting Daniel Ricard, a Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) scientist, “the most likely cause of the increase in natural mortality is an increased predation by grey seals.” Strangely, Withers makes no mention of the already released Senate report in his piece.

But what Withers does do—as many journalists have done for years—is not only repeat the official narrative about seals and fish but he omits important information that either challenges the accepted story or raises important questions about it.

For instance, Withers says the dire situation for cod in the southern Gulf of St. Lawrence “leaves DFO with few options to try to rebuild the stock,” and that killing seals will likely have a greater impact on the survivability of cod than reducing bycatch would.

How does he know that? How does anyone know that, when there are so many unknowns, not the least of which is that the bycatch problem in the redfish, halibut and turbot fisheries is likely very highly underestimated.

Nevertheless, Withers makes the statement, “reducing bycatch will hurt those fisheries with relatively small benefit to cod.”

There is also an important omission in Withers’ CBC piece that I want to raise here.

The piece focuses on the southern Gulf of St. Lawrence cod stock, which according to the latest DFO assessment declined from 13,900 tonnes of fish capable of reproducing (ie. spawning population) in 2019 to 12,000 tonnes in 2023. Withers writes, “there has been a moratorium of directed cod fishing in the southern Gulf of St. Lawrence since 2009… even with no fishing, long-term projections indicate cod in this area are on their way to commercial extinction.”

On their way to commercial extinction?

Withers makes it sound like this is a new thing. He should have made it clear to readers that cod stocks in that region were considered endangered well before directed fishing was halted there. In other words, cod were still being fished despite being endangered. A moratorium on directed fishing was finally imposed in 2009, but by then it was likely far too late. Not only that, cod were being caught accidentally in other fisheries including shrimp and lobster. In 2008, DFO scientists were already saying this particular stock was doomed, as was white hake and winter skate, and would be extirpated within 40 years without a cod fishery and in half that time with one. “Even small fishery removals will substantially hasten its demise,” one report warned.2

In other words, Withers doesn’t mention that the closure of the directed fishery in 2009 likely came too late for that stock. The omission gives more credence to the possibility that the seals could be to blame for the stock’s current situation, but important research that appeared in the journal Science more than a decade ago shows otherwise. According to the study authors, including Hutchings, if decisive action in reducing fishing is not taken in a timely manner, recovery is unlikely. In other words, killing seals will not make any difference to the recovery of that stock, according to the available science. Politics, however, is another matter entirely, and it certainly welcomes scapegoats.

In addition, Withers doesn’t even mention the murky territory of seal diet studies. Back in 2008, just before DFO minister Gail Shea placed the moratorium on directed fishing of the Southern Gulf cod, DFO scientists did raise the possibility that adult fish in that stock were “missing” as a result of the growing grey seal herd, but they noted that this hypothesis was “inconsistent” with the available science on seal diets, which shows that cod make up a very small proportion of the seal diet, and what they do eat tends to be young fish, not the adults.

Northwest Atlantic Fisheries Organization (NAFO) fishery management areas and main grey seal pupping colonies in Atlantic Canada. Source: The Devil and the Deep Blue Sea—An Investigation into the Scapegoating of Canada’s Grey Seal (2013).

‘Conducting an experiment in the open ocean’

In my book, as well as reprinted here, I explored the available scientific research about grey seal diets, and found it to be not only very complex, but also far from definitive, potentially misleading and prone to bias. I won’t go into all the details here – I’ll refer you to the 3-part series – but suffice it to say that pointing a finger at the grey seals is overly simplistic.

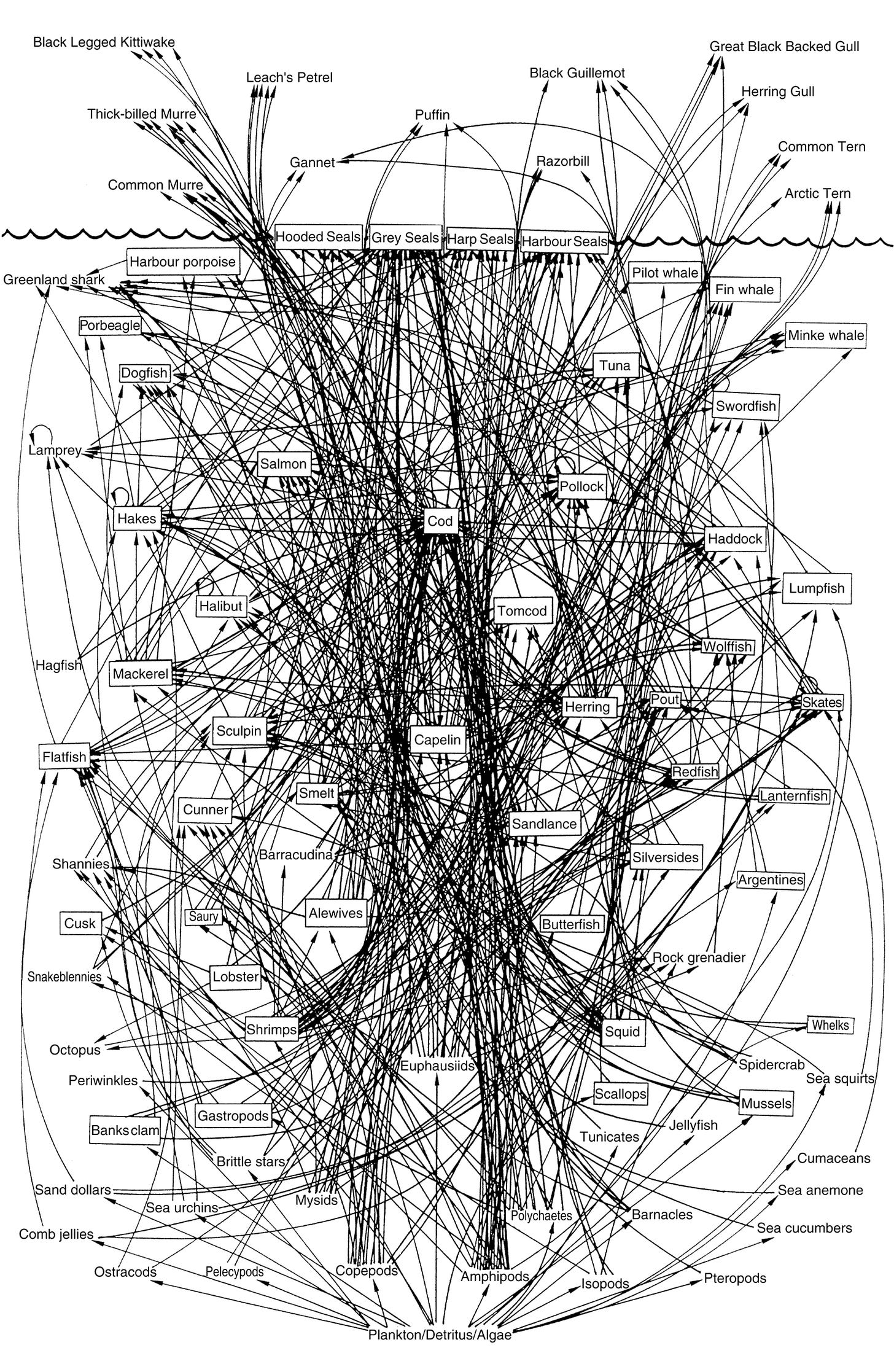

The marine food web features an overwhelming number of evolving interactions, the majority of which we know precious little about. Food webs also involve feedback loops that are themselves complicated by the fact that fish rarely eat the same foods as they grow and develop. For instance, a juvenile cod dines on a cornucopia of floating life: copepods, small crustaceans, and plankton, so it eats at a lower trophic level than an adult cod, which will eat just about anything, including other cod. The adult fish are so cannibalistic that cod jiggers — a baitless piece of lead used to attract cod by anglers — are often shaped to resemble a young cod. In one stock it was estimated that large cod were the most important predators of small cod and that cannibalism accounted for 44 percent of the juvenile mortality. So when a seal eats an adult cod, for instance, there can be a number of spin-off effects because it’s also eating a predator of small cod and other potential prey such as capelin, herring, sand lance, turbot, crabs, shrimp, and brittle stars, to name a few. In other words, when all the possible interactions are factored in, there’s every possibility that grey seals could be doing more to help cod than to hinder it.

During the Senate committee hearings, Sara Iverson testified about the complexity of the system. Iverson is a professor emeritus at Dalhousie University’s department of biology and science advisor to the Ocean Tracking Network. She told the committee that it was “very dangerous to think about an ecosystem as a two species ecosystem with one predator, the seal, and one prey.” She said that the food web looks more like a “spiderweb,” and that seals just happen to be more visible than other predator species including larger fish, whales, sharks, etc.

From Iverson’s testimony:

The other important thing to remember is seals are visible. They surface, and individual seals can be seen by fishers. There are many very large species that also eat fish — other fish — whales, such as minke, pilot whales, fin whales, porpoises, dolphins and sharks all have to eat fish, like tuna and swordfish. These are all really important predators of fish in the ecosystem.

To think that the simple solution of just removing one of those predators, being seals, will make things go in a direction we can predict is simply not the case.3

Iverson points out that “when the Atlantic cod population crashed and the moratorium started, that was exactly the time that the grey seal population started to exponentially increase. That is, when there were no cod.”

Iverson warns the Committee against “conducting an experiment in the open ocean.”

It sounds great on paper, but in practice, I don’t think it is possible. Seals, other marine mammals and sharks are very mobile species. We know from our tracking studies that, for instance, grey seals target certain areas and move between them to reach the forage areas they want… If we tag a seal on Sable Island, it moves throughout the Scotian Shelf up to Newfoundland into the gulf. Tuna and great white sharks are moving all across the Continental Shelf up into Newfoundland, the gulf and even across into Europe. So, we would not be able to say what effect reducing predator population locally would have. That has been the problem in the past with any of these efforts that have been conducted to try to reduce marine mammal populations.

When it comes to the effectiveness of culling seals to benefit fish, Iverson continues:

There are numerous examples from around the world and throughout the 20th century of large-scale reductions and the removal of seals and other marine mammals from ocean ecosystems. In almost all cases, these removals had either completely unknown or no effects on the fish stocks that were of interest, even in cases where substantial reductions in the marine mammal populations occurred.

Iverson was referring to DFO’s own 2011 scientific review of the literature worldwide on this subject which concluded there was little evidence that culls of marine mammals work and that there was every chance they could backfire. The study looked at 30 examples of massive culls and found that either the result was unknown, there was no noticeable response by the prey species, or the prey species was even worse off after the cull.4

Grey seals have already been the target of culls in the Gulf of St. Lawrence between 1978 and 1990 and elsewhere along the east coast, except for Sable Island, between 1967 and 1983. Culls of grey and harbour seals have already taken place here in the name of cod, salmon, mackerel, herring, lobster and fishing gear. The results of every single one is unknown.

During our interview when I was researching my book, Hutchings pointed out that tinkering with the marine ecosystem in an attempt to solve some problem is pure folly.

In other words, there’s no way to predict a cull would result in the desired outcome.

Hutchings:

“I don’t think any scientist with any integrity would want to make that kind of forecast. If you remove grey seals, then other things that grey seals consume, like herring and mackerel might increase and they consume cod eggs, and young cod, and so you might not actually make a difference at all. You remove one predator of cod, but you might increase the abundance of two others.”

Partial food web for the Scotian Shelf. Species enclosed in rectangles are also exploited by humans. Reprinted with permission from David Lavigne (2003).

What are some of the other hypotheses?

The recent CBC piece also makes it sound like there are really only two hypotheses about why the southern Gulf cod stock has failed to recover (ie. grey seal predation and unreported catch) when in reality there are numerous hypotheses, including that cod are now maturing sooner and dying earlier, there are large-scale ecosystem changes causing a shift in predation patterns, there’s chemical contamination, there are dead zones, noise disturbances from seismic testing and exploratory drilling, and invasive species.5

Any of these potential threats could also seriously weaken an adult cod, making them much more vulnerable to predation, but if that’s the case can you really blame the seals?

Then there are the cumulative effects of all the potential threats on these fish—something which is rarely, if ever, studied. All of these combined might be to blame for the loss of adult fish.

There are also the effects of bottom trawling on cod habitat structure, which may not affect the adult fish per se, but to the degree that fishing destroys seafloor habitat it also effects juvenile cod survival rates. So, even though habitat loss might not directly affect the fish that did make it to adulthood, it is affecting the recruitment of young fish, and is a threat to the recovery of the species.

Yet, habitat destruction has garnered none of the attention that grey seals have.

After bottom-trawling. Screen shot from report by Marine Conservation Biology Institute for the Deep Sea Conservation Coalition.

Cod endangered but never listed, why is that?

When I interviewed Jeff Hutchings for my book, there was something he told me that surprised me at the time. I had just assumed that Atlantic cod – the beleaguered fish on the doomsday list of species – was officially “listed” and that efforts were being made to protect them. But Hutchings explained that while all endangered and threatened species should be legally listed, they aren’t necessarily, and that listing would automatically result in a recovery strategy.

Four stocks of Atlantic cod have been identified by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) as “endangered,” but they have not been officially listed. Hutchings, who chaired COSEWIC from 2006 to 2010, says this is because of what are called “socio-economic” consequences, which the DFO have concluded would be “excessive.”

Listing cod would prohibit selling it and while there are still some cod fisheries open, this would result in the loss of jobs; listing would also affect other groundfish fisheries, namely yellowtail flounder, skate and redfish, in which cod is often caught incidentally as a bycatch. Hutchings explained: “DFO has sent a clear signal that any species perceived to be of economic importance will not be listed under SARA.”

Hutchings:

From a personal perspective, and for ethical reasons, the deliberate killing of one native species for the sole purpose of possibly increasing the economic gain obtained from harvesting another native species is something I cannot condone. From a professional perspective, the likelihood that a seal cull will lead to measurable and substantive increases in the abundance of cod is not known. Given such uncertainty, the ‘potential’ benefits of a cull, from a fisheries-improvement perspective, would seem to be outweighed by ‘known’ costs – such as national and international outrage – and by potential, albeit unknown costs, such as rendering the recovering prospects for cod, and other species, potentially worse.

Hutchings also pointed out that culls are never proposed in an attempt to save fish, but rather to save fisheries.

Scapegoating seals is politically necessary in order to maintain the status quo in the fishing industry. This is not to say grey seal abundance doesn’t play some role in hindering cod, but it is only one of many reasons for the failure of cod to recover, most of them anthropogenic.

A decade ago, at the time I was writing my book, the intricacies of the marine food web were being boiled down to one simple mathematical equation: less seals equal more cod. The same is true today. Once a story gets planted, and is continually reinforced and repeated, it may as well be a fact it seems, and when this happens it takes a huge amount of effort to correct it.

If mis- and disinformation needs to be rooted out, we should be starting in this case with the official narrative.

The nine recommendations from the 2024 Standing Senate Committee report: 1) Government should develop and implement a seal population management strategy, no later than six months from the date of tabling the report; 2) Rapid development and implementation of marine and fisheries research capacity; 3) More science re: seal populations, their diets, and their distribution; 4) Urgent review and amendment of Income Tax Act to ensure that registered Canadian charities and non-profits that produce or promote misinformation / disinformation about seal harvest or seal products have tax-exempt status revoked; 5) Government develop and education campaign about Canada’s seal populations, seal harvest, and seal products industry; 6) Create an anti-misinformation /-disinformation campaign related to the Canadian seal harvest and seal products industry; 7) Increase the seal harvest and make commercial sealing economically viable; 8) Government should create a Seal Studies Centre of Excellence, supported by DFO; 9) Government, led by Global Affairs, should urgently develop a domestic and international campaign to promote seal products.

The committee also suggested a “four-pronged” approach to countering misinformation and disinformation: de-bunking, pre-bunking, an initiative to produce and popularize information and to disseminate it using social media and other platforms, and the use of storytelling as a means to help Canadians learn about the social and economic impacts of Canada’s seal harvest and including through school curriculums in all Canadian schools.

Swain, D.P. and G.A. Chouinard. 2008. “Predicted Extirpation of the Dominant Demersal Fish in a Large Marine Ecosystem: Atlantic Cod in the Southern Guld of St. Lawrence.” Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 65: 2315-19.

Bowen, W.D., and D.C. Lidgard. 2011. Vertebrate Predator Control: Effects on Prey Populations in Terrestrial and Aquatic Ecosystems. DFO Can. Sci. Advis. Sec. Res. Doc. 2011/028.

Unreported catch or “bycatch” is a term used to describe those fish taken by accident in trawl nets, gill nets, longlines and even traps. Some accidentally caught fish are allowed to be kept and sold: these fish are recorded in fishers’ logs and verified by dock-side observers. But the rest are wasted and discarded, either dead or in poor condition, and never reported.

The notion of managing populations always freaks me out. Humans, too? Just look: here's another slide along the slippery slope of normalizing the control of so-called "misinformation." Sigh.

Excellent piece thoroughly documenting the scientific uncertainties that the Senate committee ignored. As usual, the news media faithfully follow the official narrative, framing it in simplistic terms. This is a common fault because journalists depend so heavily on official sources. And, as shown here, once the frame is set, it's almost impossible to overturn it. The late media scholar Richard Ericson showed how reporters use what he termed "a vocabulary of precedents" as they follow familiar narratives that have been used repeatedly in the past. These ready-made frameworks for organizing information allow reporters to present it in easily-digestible forms. In this case, seals are cast as the villains in a standard news narrative about deviance and control. Unfortunately, as also shown here, that narrative is false.