Nothing to Fear: The Unvested Interests of Rosalie Bertell

Part 4: Exposing the lie of the 'peaceful atom' and being the 'voice of the voiceless'

“We have to be part of something larger than ourselves, because our dreams are often bigger than our lifetimes.” – Rosalie Bertell

In 1980, when Rosalie Bertell made the move from Buffalo, New York to Toronto, Canada—the country of her mother’s birth—it’s hard not to imagine that her decision had something to do with fearing for her physical safety. Recall, it was just a year earlier that Bertell’s life was threatened in Rochester while driving back from a talk she gave on the dangers of radiation.

But if worries about safety influenced her move, she didn’t say it publicly. Publicly, she said she was attracted to the fact that Canada didn’t have any nuclear weapons, didn’t have a “superpower mentality,” wasn’t engaged in the “constant escalation of the nuclear arms race.” Canada was a place where she could “work creatively for a peaceful and free world” and where she didn’t “have to respond to the ‘next generation’ of weaponry.” 1

Bertell would soon learn that Canada wasn’t as safe as she’d hoped. She was also not naïve. Working on her forthcoming book—No Immediate Danger: Prognosis for a Radioactive Earth—she was well aware that Canada had plenty of its own nuclear baggage.

Rosalie Bertell (third from left) at the International Medical Commission of Bhopal (public domain)

Bertell took a position in Toronto with the Jesuit Centre for Social Faith and Justice as its specialist in energy and public health—a position she held for roughly 3 years. It was not long after moving into the Jesuit Centre’s residence, fears for Bertell’s security arose. According to her biographer, Mary-Louise Engels, as soon as Bertell arrived at the centre, there were three “troubling incidents” just a few weeks apart: first, an intruder entered the Jesuit centre, then there was a break-in, and finally, a shooting occurred “producing two holes in one window and one in another.” According to Engels, the police seemed to downplay the events and “concluded [the incidents] did not constitute a pattern of conspiracy or harassment.”2

Despite the concerns she may have harboured privately, Bertell continued her normal activities—public speaking, research and writing, and consulting on numerous issues all over the world. That same year, Bertell was recognized for her contribution to the field of public health with a number of international awards.

Bertell stayed with the Jesuit Centre for roughly three years, and then in 1983—as mentioned in Part 2 of this series—she, along with renowned physicist and peace activist Ursula Franklin, and Dermot McLoughlin, a medical radiologist, founded the International Institute of Concern for Public Health (IICPH) and set up a small office in Toronto. The focus of the organization was environmental hazards—not just nuclear ones—and it would publish a journal International Perspectives in Public Health, with Bertell as the editor-in-chief.

The connection forged between Bertell and Franklin was an interesting one. Both women—highly respected in their fields—were raising alarm bells about the machinations of the military industrial complex. Franklin was a physicist and a pacifist. In an earlier series in The Quaking Swamp Journal titled, Remote Control, I introduced you to Franklin to draw your attention to her writing on the “technological imperative,” a term she used to describe what drives the arms race. Franklin argued that governments had to provide “political justification” for the highly capital-intensive industry through the creation of an enemy, either foreign or domestic, as a “permanent social institution.”

Franklin’s work complemented Bertell’s. As we’ve explored and will continue to explore later in this series, Bertell was also a pacifist and was very critical of the war/death machine, the secrecy behind the arms industry, as well as its driving forces. While the focus of most of her career was on the health effects of radiation, she was also highly attuned to the danger the military-industrial complex posed on society if left unchecked. She argued that people would ultimately have to make a choice about the kind of world they wanted: “a system of encouragement and cooperation, on the one hand, or a system of threats and forceable control, on the other.”

Ursula Franklin (16 September 1921 – 22 July 2016)

There were many issues the IICPH eventually set its sights on, but among the first were the effects of uranium mining on Indigenous communities in Canada.

A little-known fact is that it was uranium from Canada’s Eldorado Mine in Port Radium, Northwest Territories—at the edge of the Arctic Circle—that was used for the Manhattan Project and the world’s first atomic bomb. In fact, Canada’s supply and transportation networks were crucial to the war years, making it a leading exporter of the uranium oxide-rich ores at that time. But in 1943-44, before the bombs were dropped on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the mine had changed hands – secretly expropriated by the federal government to “ensure an adequate supply of uranium for U.S., British and Canadian atom-bomb experimenters.”3

In 1982, as Bertell was just about to embark on starting the IICPH, the Eldorado mine was shut down, the settlement was razed to the ground and two years later the site was decommissioned. It would take another 22 years before remediation of the site was complete.

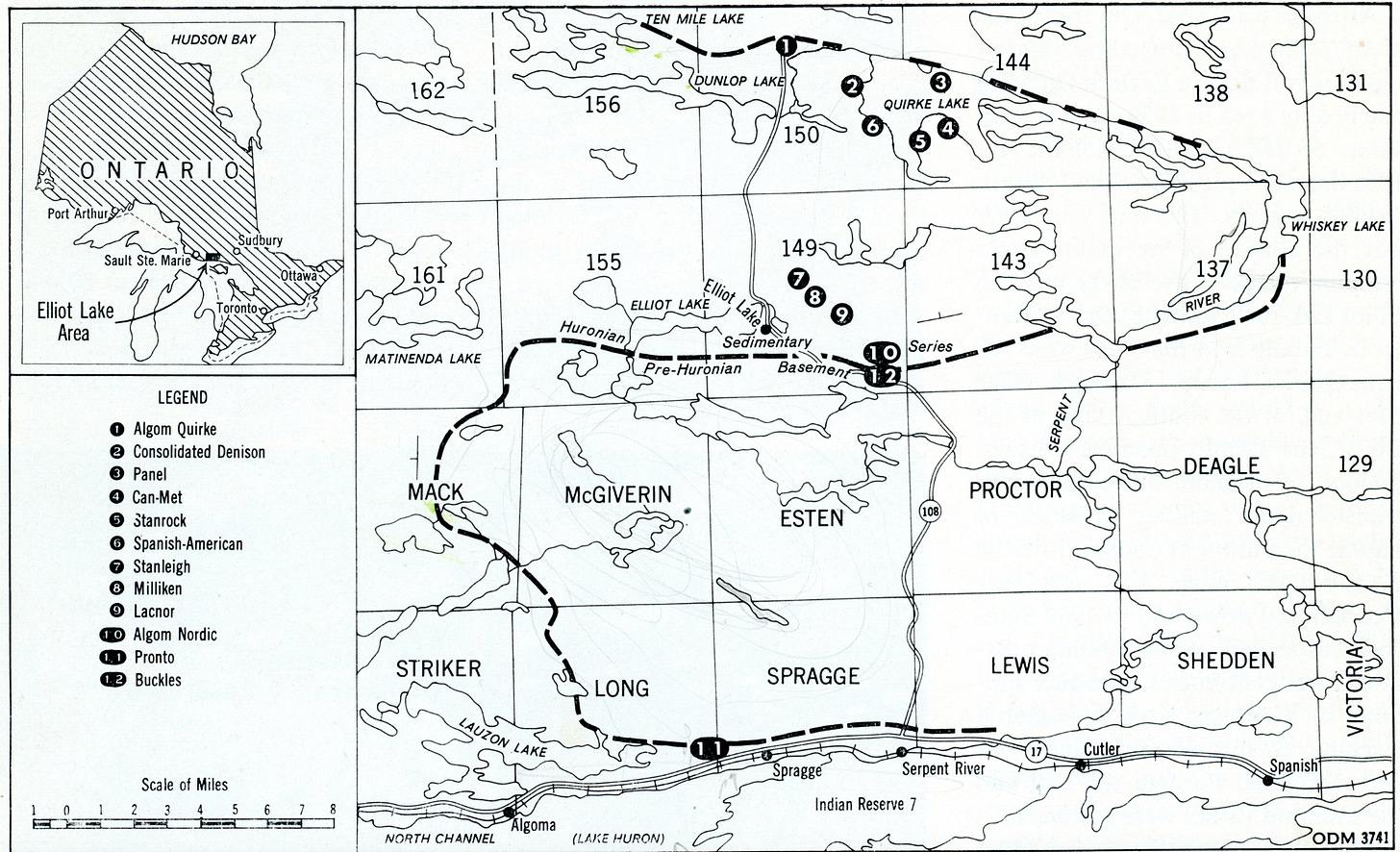

As was often the case, the mining of uranium took place not far from First Nations communities—in this case near the Dene village of Deline, in the NWT. But the Serpent River band near Elliot Lake, Ontario, and the Caribou Inuit near Baker Lake, Northwest territories suffered the same fate. In every case the mines would leave behind “disaster zones, where tons of radioactive mine tailings scar the landscape,” according to Engels.

In her 2005 book, Rosalie Bertell: Scientist, Eco-Feminist, Visionary, Engels writes that Bertell was very concerned about the radioactive sand left on the land that would blow in the wind and land on vegetation, contaminating lakes and rivers, and thereby entering the food chain. But, as her years advocating in the US have shown, Bertell was also concerned about working conditions, and whether workers were informed of the dangers. In 1999, the CBC reported on how Indigenous men recruited to work at the Eldorado site did so unprotected, and were not warned of the health hazards “even though the government knew.”

“… workers dressed in casual clothes and uranium dust covered the men like flour,” reported the CBC piece, which also pointed out that the federal government knew as early as 1932 that precautions should be taken when handling radioactive materials because ingestion of even “small amounts of radioactive dust… over a long period” could lead to “serious consequences [including] lung cancer, bone necrosis and rapid anaemia.”

This information was never shared with members of the Deline band council.

Elliot Lake uranium mining—from 1955 to 1996, Elliot Lake operated 12 uranium mines on the traditional lands of the Serpent River First Nation.

Bertell had witnessed the obfuscation and lies so many times before. Mineworkers and the communities surrounding these sites faced multiple hazards from the operations and Bertell took it upon herself to visit many of the northern uranium mining communities and conduct comprehensive Community Health Surveys. For instance, the first time she conducted the survey was with members of the Serpent River band near the heavily contaminated region of Elliot Lake in Ontario where uranium was mined at 12 mine sites for more than four decades.

Bertell documented the community’s high rates of lung cancer and other illnesses in a report to the federal government. Her efforts contributed to the government clean-up of an abandoned sulfuric acid plant on one of the sites.

According to her biography, Bertell was also called upon by the Inuit to help them oppose a German company proposal for open-pit uranium mines in the Baker Lake region of the Northwest Territories. The proposed mine would have been located in sensitive caribou habitat. Bertell and two other experts were hired to assist the Citizen’s Committee in opposing the project during the environmental assessment process. The project was delayed indefinitely and eventually, in 2015, after Bertell’s death, the Nunavut Impact Review Board rejected it.

Bertell also set her sights on other contamination exposure issues closer to home including the radioactive waste that was buried under a residential area in Scarborough, Ontario—which became known as the Malvern Remedial Project.

Even though Canada had the reputation of being a peace-loving country—having only developed the mines and nuclear power generation, as opposed to manufacturing nuclear weapons—it was actually “entangled in nuclear weaponry” because, as Bertell argued, it was impossible to separate the two.

Nuclear weapons production requires public acceptance of its support industries, such as mining, milling, transportation, refining, enrichment, fabrication, deployment, decommissioning, and waste disposal. This total industry acceptance is, of course, automatic if the public accepts these industries as necessary for solving the energy crisis. Universities would hardly have a major in engineering weapons of mass destruction [but] they will train physicists and engineers to work for the ‘peaceful atom.’4 5

At the time, Canada also had five nuclear power plants, three in Ontario, one in New Brunswick, and one in Quebec. The Gentilly-2 Facilities, located on the south shore of the St. Lawrence River in Bécancour, Quebec were shut down in 2012.

All of them were run using Canada’s own CANDU (Canadian Deuterium-Uranium) reactors.

From Bertell’s book, No Immediate Danger:

Canada pioneered and built the successful CANDU reactor, a pressurized heavy water moderated and cooled reactor. By using an isotope of water (deuterium) which is heavier than the more abundant form of natural water, the CANDU reactor achieves the two-loop advantages of American PWR [pressurized water reactor], without necessitating as high a pressure. The CANDU reactor, while it has many safety advantages, is also one of the reactors most vulnerable to theft of fissionable materials. Spent fuel rods from all types of nuclear reactors contain plutonium which can be used for nuclear bombs. A CANDU reactor, however, can be refuelled while operating, making theft of plutonium without detection possible. Other reactors must be shut down for refuelling. It was spent fuel rods from a CANDU reactor which provided the plutonium for India’s nuclear bomb exploded in 1974.

India’s first nuclear weapon’s test at the Pokhran Test Range in Rajasthan was astonishingly code-named Smiling Buddha.

While Bertell acknowledged the nuclear industry was powerful, she also tried to de-mystify that power:

“There is no incredible nuclear machine, it’s just a bunch of people. We give it power when we declare ourselves helpless,” she was quoted saying.

People opposed to militarism “were choosing war” when they supported policies or funding of any of the nuclear weapon’s support industries, Bertell argued.

Screen shot of Point Lepreau Nuclear Generating Station, about 50 km from St. John, New Brunswick. Image from New Brunswick Media Co-op

During her years heading up the IICPH, Bertell would play a role raising awareness about many public health issues, including in the aftermath of two of the world’s worst industrial disasters.6

The first event took place in 1984 at Union Carbide’s pesticide plant in Bhopal, India resulting in the release of a lethal chemical cloud that immediately killed more than 2,000 people and left more than 600,000 injured. A decade later, Bertell co-chaired the International Medical Commission on Bhopal, which was set up by the Permanent People’s Tribunal to address unresolved violations of human rights. Bertell and others visited the affected people and investigated survivor’s medical issues, treatment, and compensation.

Two years later, in 1986, the world’s largest nuclear accident took place at the Chernobyl power reactor about 130 km north of Kiev, Ukraine. The release of radioactivity spread all over the world contaminating parts of Europe and the former Soviet Union. According to her biography, Bertell travelled to Kiev shortly after the explosion, then again in 1991. She was in touch with Soviet scientists and tried to understand the “discrepancies between official estimates of damage and those produced by independent researchers, some of them eventually silenced by imprisonment.”

In 1996 Bertell was chosen to chair the International Medical Commission on Chernobyl, and brought in 40 international witnesses to examine the consequences of the catastrophe. In Bertell’s testimony we learn that about 600,000 men were conscripted as Chernobyl ‘liquidators.’ “They lifted pieces of radioactive metal with their bare hands… they fought more than 300 fires… they buried trucks, fire engines, and cars; they felled a forest and removed topsoil.” Many died, either immediately or later on from a variety of radiation induced illnesses.

In 1997 Bertell sent recommendations to a health ministers’ meeting at the World Health Organization, expressing concerns about the promotion of nuclear energy, which was “associated with the production of dangerous, carcinogenic, teratogenic (embryo damaging), and mutagenic (mutation causing) substances.”

In 2007, text written by Bertell appeared in a book of photos, Chernobyl: The Hidden Legacy, where she wrote:

“At Chernobyl, with millions of exposed persons in rural un-evacuated areas, hundreds of thousands evacuated but not medically examined, and with the population’s continuous ingestion of contaminated foods for the past twenty years, for experts to demand documentation of radiation sickness is ridiculous.”

As previously mentioned, Bertell traced the permissible dose levels for radiation back to the US military experience in Nagasaki and Hiroshima, Japan, where two atomic bombs were dropped within days of each other in 1945. The effects of the bombs were collected by the Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission (later renamed the Radiation Effects Research Foundation or RERF). In Chernobyl, Bertell wrote that the use of “external high-level irradiation by a bomb” to evaluate “civilian exposures to protracted low-level inhaled or ingested radionuclides led to “inappropriate behaviour of officials with respect to the medical treatment of survivors of Chernobyl.”

Bertell also said that using this research to train young physicists and nuclear engineers led to “many scientific blunders” and “an artificial consensus among experts.”

“The failure to deal with the whole breadth of radiation problems became entrenched in the very agencies that were created in the 1950s to protect the public at risk from atmospheric nuclear testing.”7

Bertell observed that standards of radiation safety were developed by the International Commission on Radiological Protection (ICRP) a “self-appointed non-governmental organization” that formed in 1952.

Bertell described a captured system:

[The ICRP] was formed by the physicists of the Manhattan Project who had hammered out radiation standards between 1945 and 1950, together with the Medical Radiologists, who had organized themselves in 1928 to protect themselves and their colleagues from the severe consequences of exposure to medical X-ray… Members of the ICRP are appointed by current ICRP members, and accepted by the ICRP Executive Committee. They are self-perpetuating, and no outside agency can place a member on the ICRP…. [The ICRP] has given itself the task of recommending a trade-off of predictable health effects of exposure to radiation for the benefit of nuclear activities, including the production and testing of nuclear weapons.

Malformed fetuses due to the Chernobyl disaster located at the Institute of Anatomic Pathology, Belarus. Photo taken by Italian photo-reporter Pierpaolo Mittica appeared in his book, Chernobyl: The Hidden Legacy, 2007.

In 1987, when Maureen Wild was studying at the University of Toronto towards a Spiritual Theology Diploma, she was required to do an internship and says she “immediately” thought of Rosalie Bertell and the IICPH. Wild had attended two talks given by Bertell and found them “very compelling,” she tells me in an interview over Zoom.

“There are markers in a person's life that can change the way you think, and sometimes it can happen very quickly. The effect of Rosalie’s talk in that keynote address—it was about an hour long—was one of those markers in my life that changed me completely and turned my worldview of separation upside down,” Wild recounts.

“I grew up very connected to nature but I didn't realize how integrated the human was with everything else. I remember Rosalie used the image of the Earth from space, and a fetus in the womb, and she said, ‘What we do to the waters of one, we do to the other,’ and ‘what we do to the air of one, we do to the air of the other ... to all others, and what we bury into the crust of the earth, we bury into our own bones ... and the bones of all other beings."

“It was like a litany—all of which had a deeply profound effect on me as it tumbled out of her.”

Wild was thrilled when Bertell said, ‘yes’ right away to her request to do an internship at the Institute. At the time “it was gathering information from all over the world. I felt somewhat overwhelmed by the magnitude of it.”

According to Wild, Bertell was basically driven to advocate for those whose rights were often “usurped.”

“[She] had a huge heart for the most vulnerable, the poor—a huge empathy. I don't know how that all developed within her,” says Wild.

“Her eyes sparkled. She radiated joy. She was personally very, very present. When we sat down with our bag lunches, you were the only one in the world with her.”

“She was my Rachel Carson,” says Wild. “She challenged her audiences to follow a deeper calling in life for the protection of life.”

Maureen Wild did an internship with Bertell at the International Institute for Public Health in 1987. Photo of Maureen and Belle, contributed.

Wild:

“Rosalie was very courageous and prophetic. Though she wasn't looking out to be prophetic. It’s just that she was so brilliant and knew so much and she knew how to name the truth. She was a truth teller. She didn't seem to have any fear, even though her life had been threatened.”

At the end of her internship, Bertell invited Wild to stay on to help with an educational project that she was trying to secure funding for to create educational materials about the “health effects of low-level radiation, with global examples on the devastating health effects to poor communities and indigenous peoples who'd been exposed to radiation waste in their local environments either through intentional or accidental discharge from industries and military testing,” explains Wild. Bertell had asked her to be involved in creating the materials, but the fundraising came up short and the project did not go ahead.

“It was terribly disappointing for me but I had to accept the reality and move on,” says Wild, who went on to teach inner city children in Boston. “Rosalie and I kept in touch throughout the years, and I would always receive her great encouragement and affirmation of the spiritual ecology work that had become the primary path of my ongoing contemplation, and educational and retreat ministry.”

Even near the end of her life, Bertell was unstoppable, says Wild.

“Even in her frail state, she would go to her room and sit at her desk and be communicating with people from different parts of the world, being their resource person, doing whatever she could to help. She still understood the physics and chemistry and how to analyze it and how to encourage the correct kind of collaboration and strategies.”

“Rosalie was the voice of the voiceless. An advocate, a collaborator. A giant in our midst.”

Postscript: A huge oversight on my part — I forgot to mention Chalk River Laboratories in Ontario— established in 1944 by the National Research Council as a research site for nuclear technologies — particularly the CANDU reactor. It also supplied (1955-1985) plutonium to the US Department of Energy to be used in the production of nuclear weapons. It was the site of two nuclear accidents in the 1950s, both requiring huge clean up efforts with both civilian and military personnel. The site is still in active use and is now called the Canadian Nuclear Laboratories Research Facilities. For more on this subject go to this aptly named piece.

[I cannot say yet for sure, but Part 5 might be the final part in this series. However, as I am posting each instalment as I write it, and still have a lot to read, there could very likely be two more parts. In any case, coming up, I’ll be exploring Bertell’s last book – Planet Earth: The Latest Weapon of War. I hope to post Part 5 in early February. Thanks for reading!]

From Bertell’s acceptance speech for the Sean MacBride Peace Prize, which is given annually to a person or organization that has done outstanding work for peace, disarmament and/or human rights. Engels, 2005, p. 100.

Engels, 2005, p. 107.

Quote taken from Time Magazine archive.

Engels, p. 116.

Another organization (one that I’m personally familiar with) that takes on the nuclear industry and advocates for the interests of communities in the north is Northwatch – founded in 1988 by the indefatigable and eloquent Brennain Lloyd. Among the numerous environmental issues it tackles, the organization has taken on the work of informing the public about nuclear waste burial in Canada, and to help communities who “may find themselves entangled in a siting process for nuclear waste and to support communities who may find themselves unwilling to take on such a burden but find themselves en route between the reactors – where the waste is currently stored – and a community that is being considered as a possible recipient of the waste.”

In addition to playing a role in the aftermath of the Bhopal and Chernobyl disasters, Bertell assisted the people of the Philippines with problems stemming from toxic waste left by the U.S. Military on their abandoned Subic and Clark military bases. She worked with the government of Ireland to hold Britain responsible for the radioactive pollution of the Irish Sea, and assisted the Gulf War Veterans and the Iraqi citizens dealing with depleted uranium and the illness called Gulf War Syndrome.

The agencies Bertell was referring to were the International Atomic Energy Agency, the United Nations Scientific Committee on Atomic Radiation, the International Commission on Radiological Protection, and the World Health Organization. Bertell’s text can be found in Mittica, Pierpaolo, 2007, Chernobyl: The Hidden Legacy, pp. 196-207.