Nothing to Fear: The Unvested Interests of Rosalie Bertell

Part 7: Ursula Franklin, demilitarization, and mapping how to get there

[Part 6]

When Rosalie Bertell died of cancer on June 14, 2012, at the age of 83, obituaries, including this one by Right Livelihood, recognized her for sparking awareness “about the destruction of the biosphere and human gene pool, especially by low-level radiation.”1 Twenty-six years earlier the same organization gave Bertell its prestigious award—one often referred to in the media as the alternative Nobel Prize—for her work with the Toronto-based International Institute of Concern for Public Health (IICPH), which Bertell founded along with Ursula Franklin, a University of Toronto professor who was renowned for her seminal work on the effects of technology.

Vandana Shiva, Edward Snowden, the late Daniel Ellsberg, Maud Barlow, and David Suzuki are also among the award’s recipients.

In her acceptance speech for the organization’s cash prize—nearly four decades ago—Bertell was prescient:

This [award] is a much-valued service to the forming global village. In the long run it will, I think, be more humanly productive than increased airport security, military exercises, nuclear threats, and development of crowd-control technology. This contrast between a system of encouragement and cooperation, on the one hand, and a system of threats and forceable control, on the other, lies at the centre of the global crisis. It poses a clear choice for the future, on which will depend the survival or disintegration of civilization.

Given the state of the world these days—with the threats of a third world war and a system of total surveillance—it seems obvious, to me anyway, which direction we’re headed.

But if there was ever a message Bertell was hoping to convey through her life’s work, it was that succumbing to the forces of darkness was not inevitable.

We may be on a rather bleak trajectory, but there are forks in this road.

Rosalie Bertell, April 4, 1929–June 14, 2012

Earlier in this series, I mentioned that the connection forged between Bertell and Ursula Franklin was a notable one. Both women—highly respected in their fields—raised alarm bells about the often-secret machinations of the military-industrial-complex. Both were pacifists, feminists, and activists, and both formed cogent and ethical arguments against the use of war.

Franklin called it a “dysfunctional instrument of problem solving.”

“Violence begets more violence, war begets further wars, more enemies and more suffering,” said Franklin.

Bertell called it a “death machine.”

Franklin died in 2016, four years after Bertell. In life, the two women knew each other well, working together in Toronto in the 1980s and 1990s. I wanted to find out more about their connection and through a friend, made contact with Franklin’s daughter, Monica Franklin, who lives in Toronto with her family. Monica is an author, having recently published a book about her mother titled, Undaunted Ursula Franklin: Activist, Educator, Scientist, as well as a retired lawyer who worked for 20 years in the community legal aid clinic system in Toronto.

We spoke on the phone and continued our conversation over email.

Monica tells me: “As well as being respected colleagues, Ursula and Rosalie were also good friends.”

In addition they were the “only women in their respective male-dominated professions”—Franklin was a metallurgist and physicist who taught at the University of Toronto for more than four decades. In 1984, she was the first woman to be granted the special designation of “university professor.”

For Bertell, the scientific field of radiation, or later, the military, were also male-dominated.

Being so close in age—Franklin was 8 years older than Bertell—meant they also “shared some major events of world history such as the Second World War, the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the partial meltdown of Three Mile Island nuclear plant.”

Monica Franklin:

They both travelled in similar circles and had many interests and causes in common. Both were part of the women’s movement in Toronto in the 1980s, my mother particularly via the Voice of Women. Both had a strong religious and faith base for their activism: Rosalie through the Jesuits and the Grey Nuns and Ursula with the Quakers. Both were scientists, focussing their work on ‘ordinary people,’ civilians, often women and children who were frequently victims or ‘collateral damage’ (to use a modern term).

According to Monica, when her mother was asked in a 2010 interview about her familiarity with the activism of Bertell, she replied, “Our work comes out of a similar wish to make it clear that in the modern world nobody has the right to put a burden on the health of innocent people because there is no opting out.”

Throughout their careers—which took very divergent paths—their work sometimes aligned. For example, between 1962 and 1964, the Voice of Women National Committee led by Franklin, collected baby teeth from children across Canada to test for radioactive substances, particularly strontium 90, which can be detected in bones and teeth, and according to Monica, “showed how much radiation had built up in the body.”

“Since little radiation is found naturally in the human body, the study showed that children were being affected by the fallout from nuclear weapons testing, she explains.

But, according to Monica, despite their formidable accomplishments—the two women also shared something else in common.

“At the time… their concerns were often not taken seriously or downplayed. Only later did people realize the merits of what they had said, not to mention the strong scientific and evidentiary basis for it.”

A story that illustrates this for Franklin took place in 1977 when she authored a ground-breaking report for the Science Council of Canada titled, Canada as a Conserver Society. At the time, Franklin was the Chair of the Committee on the Implications of a Conserver Society, but according to Monica, “the notion that Canada needed to conserve and protect its resources was seen as not just strange but even suspect and ‘anti-Canadian.’”

“Critics said such fundamental societal changes were not justified and would lead to Canada’s economic decline. A Globe & Mail article revisited the report 30 years later, calling it ‘a revolutionary study [that] laid out for the first time a national blueprint that would lead to a healthy and sustainable society.’”2

Monica also recounts that some of Franklin’s ideas were “not popular.” For instance, in 1989, Franklin put forward the idea that “technology was not neutral or apolitical but reflected the society in which it was produced and those who designed it.”

“Her ideas, including that technology had major effects on society—not all of them positive—did resonate later however. Ursula revised and updated The Real World of Technology in 2004 and the Massey Lectures (on which the book was based) were rebroadcast in December 2020, with many pointing to its continued relevance.”

As we’ve seen throughout this series, Bertell’s work was also met with a great deal of resistance, particularly in the early years. But her work on radiation would eventually gain the recognition it deserved.

In her biography about Bertell, Mary-Louise Engels notes that among Bertell’s “treasured documents” was a letter she received from Sir Kelvin Spencer, the former chief scientist for Britain’s Ministry of Power. In 1984, Spencer wrote to Bertell following her testimony at the British Sizewell nuclear inquiry.

The letter in part reads:

“Your paper to the Sizewell inquiry is what has been wanted for decades, but only now, thanks to you has been brought into existence. All of us and our even more numerous descendants, have and will have cause to give you thanks, and learn from you how to devote one’s life to a self-imposed and exacting task.”

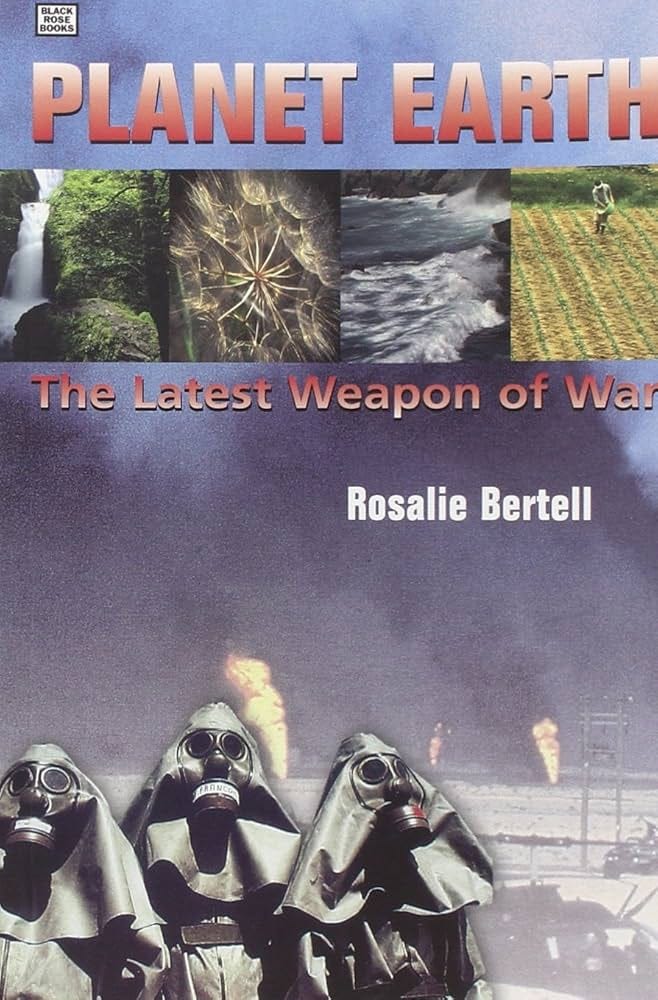

Meanwhile, as explored in this series, the subject of her last book regarding the nature of military experimentation and its effects on the atmosphere and biosphere, has garnered very little public attention.

Monica Franklin is a retired lawyer and author of the book, Undaunted Ursula Franklin: Activist, Educator, Scientist. She lives in Toronto with her family and has two sons. Photo contributed.

In Franklin’s book, The Real World of Technology, based on her 1989 Massey Lectures, she talked about the “technological imperative,” a term she used to describe the momentum that follows the adoption of a technology, and that it’s this momentum that shapes society, rather than the other way around.3

Franklin argued that the “technological imperative” applied to so many aspects of society, including the arms race, and that governments had to provide “political justification” for the highly capital-intensive industry through the creation of an enemy, either foreign or domestic, as a “permanent social institution.”

In The Ursula Franklin Reader: Pacifism as a Map—so titled, according to Franklin, because “maps are made for people to get from here to there,” Franklin wrote:

Modern weapons technologies, including the required research and development, are particularly capital-intensive and costly. The time between initial research and the deployment of weapon systems can be as long as a decade, during which the government must provide financial security and political justification for the project. In other words, the state not only provides the funding but also identifies a credible external enemy who warrants such expenditure.

Franklin’s thinking around technology often complemented Bertell’s on the war machine, in startlingly prescient ways.

Bertell was very critical of the military, the secrecy of the arms industry, as well as its driving forces. When Bertell was raising alarm bells over “the high technology atmosphere of first world [military] research,” which she said was “sending tentacles into outer space as well as colonizing sub-microscopic life,” Franklin was pointing to the “worldwide drift towards 'techno-fascism,'”— an organizing principle for globalization where technical expertise is required to gain political rights. Franklin argued this was akin to being “the anti-people, anti-justice form of global management and power sharing that is developing around the world."

Both Bertell and Franklin were clear that the arms race was a threat to the biosphere, and therefore the survival of life on Earth.4

Franklin pointed out that nature itself was a “second superpower,” and that “coexistence with the biosphere is a prerequisite for every other kind of coexistence.”

Both women also seemed highly attuned to the dark forces at work in the world.

Ursula Franklin, September 16, 1921 – July 22, 2016. Photo contributed.

If there was any doubt about what Franklin and Bertell were warning us about all those years, then the events of the last twenty years have vindicated them.

They both recognized that instilling fear in a population was a necessary step in manufacturing the consent for the trillions of dollars needed to fund the machinery of war that Bertell talked about. Fear was also necessary for the creation of a domestic enemy as a “permanent social institution,” which is something Franklin talked about.

The machinery of war has “advanced” since then and now includes digital systems of surveillance and biometric population databases, formidable tools of domestic social control, with deadly applications on the battlefield.

Previously, I explored how the US security state, for instance, is involved in the creation of a credible domestic enemy in order to politically justify the “technological imperative” by exaggerating or even fabricating the threat, with increasing evidence it may also be participating (indirectly, through funding) in “information operations”—the mis-labelling of true information as misinformation, and disseminating real misinformation and disinformation domestically.

It’s called information and cognitive warfare, aimed at non-military targets to “attack and degrade rationality” itself. An important tool in this arsenal is surveillance.

I’ve also written about how Canada has been “modernizing” or re-defining what constitutes a “national security threat,” and how this can also be used domestically to sanction a variety of forms of dissent, and create permanent enemies in our midst.

‘[M]odernizing’ the definition of what constitutes a national security threat broadens the definition to include the religiously, politically, and ideologically motivated violent extremist (MVE) who is—according to Public Safety Canada— “fuelled on disinformation” and wants to “destabilize and undermine our cohesion and confidence in our democratic institutions and processes.”

Threats to national security also include “cyber-security threats”—“informational activity” including misinformation, disinformation, and malinformation (MDM).

If the government has the authority to determine what constitutes misleading or exaggerated information, or a false narrative, and is also able to unleash a whole security apparatus to combat it, including financial tools, it’s not hard to imagine how this power can be abused to cover-up government wrong-doing, to achieve political gain, or be used domestically against its own citizens as a form of cognitive warfare.

The technology required for the kind of surveillance that exists now was not widespread when Bertell and Franklin were doing their research, though both women could see the threat looming on the horizon.

For instance, when it comes to warfare, we are seeing in Gaza (in real time) how surveillance networks can be used, where targeted, nearly autonomous bombings are made possible by Palantir's AI-generated kill lists. The targeting program called “Lavender”—about as Orwellian as you can get—relies on surveillance networks to first determine who the targets are. Another of Palatir’s AI platforms is being tested on the Ukranian battlefield. This advanced technology is being harnessed by the military, presenting commanders with targeting options, sometimes even predictive ones, compiled from satellites, drones, open-source data, and battlefield reports.

There also now exists all-encompassing digital identification, including facial recognition, drones, robot police, and big data collection targeting online social media platforms to monitor citizens and create what is essentially a “behaviour modification machine.”5 This kind of power/ control is already not conducive to a free and democratic society, but in the wrong hands it could be a dystopian horror show.

I suspect that some of my readers will disagree with what I’m about to say, but I have to say it: we already got a taste of what’s possible during the pandemic, during which many of these technologies, justified in the name of safety, were accelerated, piloted and normalized. There was an exponential surge in the level and range of surveillance, augmented by the lockdowns and stay-at-home orders. In many countries, the fear and panic that ensued was used by tech lobbyists and governments to further expand their power, some in very authoritarian ways.

In her last book, Bertell made reference to how “shock therapy” was used in the aftermath of the Cold War to help “rapidly move a country from socialism to capitalism.” She said this technique was used, for instance, to destabilize Yugoslavia’s economy through the interventions of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), which demanded the country open its economy to “full foreign ownership rights and put an end to worker participation, moving the country towards a Western-style economy.”

Many readers would also be familiar with the similar term “shock doctrine” which was the subject of Naomi Klein’s 2007 best-selling book by the same name.

Shocks or crises—whether they are real or manufactured—have been used to advance what Klein refers to as a “high-tech dystopia.”

The cover of Rosalie Bertell’s last book, published in 2000.

According to Ursula Franklin’s daughter, Monica, “militarization [is] the manifestation of the threat system (“do what I say or else”), and is “based on dividing the world into ‘us’ and ‘them’ and seeing others as ‘the enemy.’”

“Ursula wrote that militarization goes beyond training for war and preparation for combat: it is an internally consistent system of attitudes, perceptions and actions.”

Monica says her mother defined “peace” as “not just the absence of war, but the absence of fear and the presence of justice.”

It includes (actually, requires) notions of democracy. Everyone, including “the other” has something to contribute to a larger whole, called society. Ursula used to say that her vision of a peaceful world or society was a potluck supper. All are welcome. Everyone contributes: people bring what they can and do best (you don’t want everyone bringing the same thing) and everyone receives fellowship and nourishment. Ursula spoke and wrote explicitly about democracy: its importance and her concerns about its decline. She was particularly worried about the erosion of its institutions. She was concerned about how democratic institutions shut out the voices of opposition, of “ordinary people” (ie. those directly affected by decisions) and the lure of simplistic, “strong man” solutions.

For Bertell, the solution to the many of the ills facing the world was de-militarization.

But we are instead moving in the opposite direction. Global spending on the military has reached an unprecedented high. According to an analysis from the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), world military expenditure increased for the ninth consecutive year in 2023, reaching a total of $2.4 trillion.

The two largest spenders are the US and China. When combined, they accounted for roughly half of global military spending in 2023.

“Global survival requires a zero-tolerance policy for the destructive power of war,” wrote Bertell. But she also observed that the environmental movement needed to be brought on board, as it often ignored the “colossal impact of war,” or the consequences of the military’s experimentation in the atmosphere.

Bertell:

Popular support for the military comes from fear, and that fear is based on hundreds of years of recorded history. We feel that we must have weapons to protect ourselves from the weapons of the enemy. This fear legitimizes the development and stockpiling of new weapons… [and] that military might is the best assurance of security… It is vital that a new concept of security be devised, which puts Earth and its inhabitants first. The old paradigm of security protects wealth, financial investment and privilege through the threat and use of violence. The new concept embraces a more egalitarian vision, prioritizing people, human rights, and the health of the environment. Security is not being abandoned; it is just being achieved through the protections and responsible stewardship of the Earth. I would call this energizing new vision ‘ecological security.’

Bertell was prescient yet again when she argued that the new vision required the “connection” of everyone who was “working for peace, economic justice, social equity and environmental integrity.” She also held out great hope that the Internet would become a democratizing “tool for global organizing,” and that disputes would be settled by international bodies such as the International Criminal Court. This, she believed, would usher in an “exciting new era of diplomacy.”

But on all fronts, there have been developments she could not have anticipated.

First, there is now so much fracturing among progressives—the causes of which go far beyond the scope of this piece, but I will offer this observation: the focus has shifted away from class analysis rooted in economic justice, and this shift has proven to be divisive, rather than a unifying.6

In order to achieve a unified push towards demilitarization and ‘ecological security,’ and work collectively towards Bertell’s vision, there needs to be a rejection of the polarizing forces at work, and the possibility of reconciliation and redemption.

Over the last couple of decades, the Internet has also devolved into something other than what was promised. As I’ve previously written, when the Dot-com bubble started to implode in 2000, Google decided that it would take all the behavioural data that it was collecting for free to improve the user experience and commercialize it – to target advertising to individual users. The new frontier was human behaviour: a new supply of raw material in a variant of capitalism called “surveillance capitalism,” where personal data is commodified by corporations.7

In other words, the democratizing promise of the Internet has been derailed.

As Shoshana Zuboff, author of “The Age of Surveillance Capitalism,” has stated, there is a great danger when those interested in our behavioural surplus are no longer indifferent to the behaviour itself, but want it for manipulation and control.8

We have also seen recently that global bodies like the International Criminal Court — while designed to be independent with the mandate to investigate and prosecute individuals for crimes of genocide, war crimes, and crimes against humanity—are still subject to political pressure and threats of retaliation.

World military expenditure, by region, 1988-2023. Note: The absence of data for the Soviet Union in 1991 means that no total could be calculated for that year. Source: Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) Military Expenditure Database, Apr. 2024.

As we’ve seen in this series, Bertell immersed herself in such difficult subject matter and yet, she had the capacity to hold all of that in her system—over decades. But how did she sustain that? The obvious is that she had her religious faith, which she wrote, “has a profound effect on our staying power.”

“In spite of natural timidity, I have always felt invincible before hostile forces because I have been ‘redeemed.’ This means that I have all the power I need to face down evil. I have the power to choose life under any circumstance. Life is stronger than death… evil will not triumph unless we waste our power to choose life.”

Bertell was also influenced by her mother, who she remembered as being very affected by the dropping of the atomic bombs on Japan during World War II. When her mother heard the news, she was “stirring something in a big pot on the stove, and Bertell, who would have been a teenager at the time, overheard her muttering to herself over and over, “They shouldn’t have done it. They shouldn’t have done it.”

“Some people are just in tune with the pain of world,” she wrote.

Later, when Bertell took on the nuclear establishment, she said “that dramatic pot stirring” gave her “a sense of being right.”

“Rational investigations and careful research into issues are important. But the strength to stand up to forces that claim superior wisdom and a national security mandate comes from deeper down, from the fertile field of our memories,” wrote Bertell.

In her books Bertell often pointed out how scientists, whether they be government, industry or the university, were dependent on needing grants, equipment and resources. Bertell herself was in this tenuous position early on. “Most of the time you’re living on the edge,” she said, making it more difficult to take principled stances. Those that did often suffered the consequences.

While Bertell suffered financial constraints for the stances she took, she also enjoyed a certain amount of freedom and independence.

“I live on next to nothing—that makes it hard for people to put the usual pressures on me,” she said.

According to her biography, as Bertell was awaiting heart surgery in 2003, she wrote a chapter for an anthology about where activists find hope in troubled times.9 In her piece titled “In What Do I Place My Trust,” Bertell conveyed her belief that stories hold great power and inspiration. Stories like, “David and Goliath, Robin Hood, and Florence Nightingale, provide worthwhile goals and dreams of what could be.”

The “important message” in her last book “is that local problems and local solutions are of tremendous importance,” and that “small acts can have disproportionate effects.”

Bertell wrote:

The continuity of life, the call for making things better for the next and the next generations blots out all hesitation. To act becomes natural, and to not be able to act, a torment. We do not need to enjoy the fruits of our longing, as we ‘see’ them making fruit in others who will come after us. We are part of a great chain of people who care about the Earth… and about a world where rights would be respected, children cherished, and peace prevail. We have to be part of something larger than ourselves, because our dreams are often bigger than our lifetimes.

In the last lines of a speech she gave upon receiving an honorary degree at Mount Saint Vincent University in Halifax in 1985, Bertell gave her audience some instructions. “Remain clearsighted and lighthearted,” and “seek solidarity.”

And above all, “refuse to be boxed into a death pattern.”

[Postscript (April 19) I just learned that Rosalie Bertell’s biographer, Mary-Louise Engels passed away a few days ago on April 14, 2025. She was the author of Rosalie Bertell: Scientist, Eco-feminist, Visionary. You can read her obituary here. Not sure what I would have done without her little book. It was a treasure trove and I thank Engels for her work and vision to write it.]

Bertell was also the recipient of five honourary degrees and received many awards, in addition to the Right Livelihood Award including: World Federalist Peace Award; Ontario Premier’s Council on Health, Health Innovator Award; the United Nations Environment Programme Global 500 award and the Sean MacBride International Peace Prize. She was also selected to be one of the 1,000 Peace Women nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize, 2005.

Bertell spent the last years of her life with the Grey Nuns of the Sacred Heart in Southampton, Pennsylvania. Archivist Nancy Kaczmarek says that most of Bertell’s materials are stored in the Library and Archives Canada. The rest are stored at the University of Buffalo.

Illustrative of the way the regulatory agencies were captured—something Bertell railed against in both of her books—was an incident that took place in 1985, when the Mulroney government appointed Ursula Franklin to the Atomic Energy Control Board, a 5-member board that directed an agency of 285 employees “charged with protecting the Canadian public against the consequences of a nuclear mishap.” One day after her appointment, Franklin was told the invitation had been withdrawn. The public speculated that it was due to her anti-nuclear stance, of which the government was somehow previously unaware. (University of Toronto Archive)

Franklin also authored The Ursula Franklin Reader: Pacifism as a Map, a collection of her papers, interviews, and talks; and Ursula Franklin Speaks: Thoughts and Afterthoughts, containing 22 of her speeches and five interviews between 1986 and 2012.

Franklin’s views on this can be found in "Coexistence and Technology: Society Between Bitsphere and Biosphere," (Polanyi Lectures, Concordia University, Montreal, 1994 and 1995), located in her collection: Ursula Franklin Speaks: Thoughts and Afterthoughts. You can find a summary here. But essentially, Franklin’s keynote address focused on “the capacity of societies to coexist in a world transformed by technology and marked by a disregard for the environment.”

Quote by Shoshana Zuboff, author of The Age of Surveillance Capitalism.

There is a growing intolerance among so-called progressives towards debate, questions or positions that challenge certain narratives. For a deep dive into this subject matter I would highly recommend the 2023 book I’ll Burn That Bridge When I Get to It!: Heretical Thoughts on Identity Politics, Cancel Culture, and Academic Freedom by Norman Finkelstein. In it he notes that this suppression and censorship of debate/ speech/ expression (whether it’s external or self-imposed) in effect “reverses many of the hard-won gains by “the Left in conjunction with civil libertarians to curb government interference with political speech.”

Whatever the causes of this intolerance, the “left” is now very divided and the promise of a cohesive movement—that seemed possible 20 years ago—seems much less attainable today.

See Shoshana Zuboff’s book, “The Age of Surveillance Capitalism.”

It should also be noted that Google recently (March, 2025) acquired an Israeli cybersecurity company Wiz for $32 billion. According to reporting from the Grayzone, “the acquisition will mark the single largest transfer of former Israeli spies into an American company. This is because Wiz is run and staffed by dozens of ex Unit 8200 members, the specialist cyber-spying arm of the IDF [Israeli Defence Forces]. Unit 8200 wrote the programming and designed the algorithms that automated the genocide of Gaza and was also responsible for the pager attack in Lebanon. Now the men and women who helped design the architecture of apartheid are being swallowed by the US tech-surveillance complex.” The Times of Israel reported that “Google’s Wiz acquisition would be a new feather in the cap of Israeli military intelligence.”

The chapter appeared in the 2004 book titled, The Impossible Will Take a Little While: A Citizen's Guide to Hope in a Time of Fear.

Thank you Linda, for this comprehensive and courageously written series. I have learned so much. Bertell's words of encouragement to 'refuse to be boxed into a death pattern" resonates at both the personal and political level of how i would like to be able to respond to the persistent and insidious descent into technological slavery. Lately, I find it necessary to consciously enact a daily practice of willfulness -- to not slip completely into the abyss of despair. It helps to hear a robin sing a few notes announcing spring's renewal

Thanks for this series, Linda. I've really enjoyed it. I also appreciate the way you have provided context and your analysis. I've been stalled writing an essay about the use of fear from childhood on up, and you've inspired me to get back to it.