Nothing to Fear: The Unvested Interests of Rosalie Bertell

Part 2: Bertell's Nova Scotia connections

[Part 1]

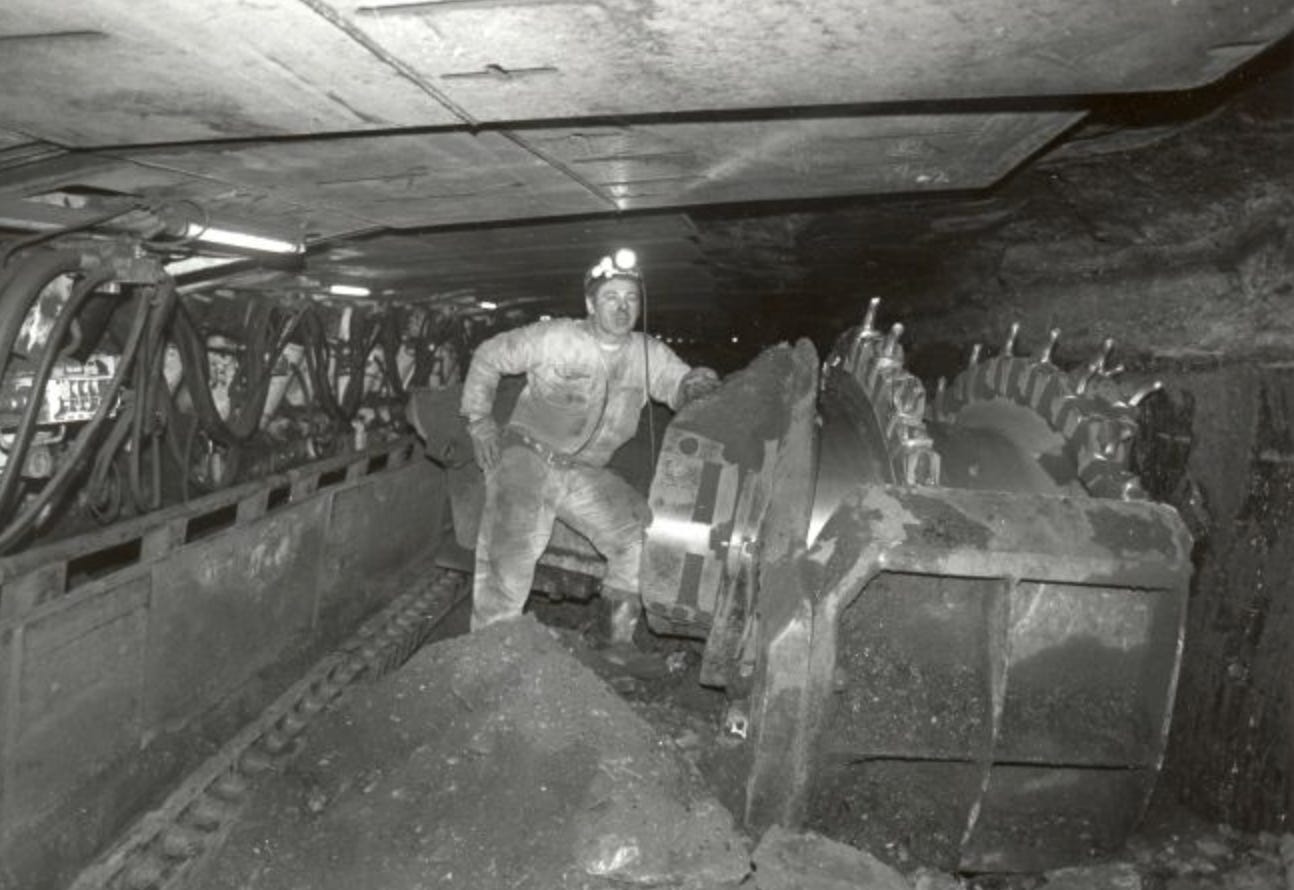

The vestiges of the round-the-clock mining operation—a long line of rail cars, piled high with coal—stood motionless on the tracks. I could almost hear the wheels grind to a halt when the Phalen mine in Cape Breton, Nova Scotia shut down for good in 2000. Rock gas bursts made the mine unsafe, and production stoppages made it unprofitable. For 13 years the industrial monolith hummed 24/7 and when operating at full tilt, more than 600 miners worked cutting away at the soft coal seams from within what some have called the darkest place on earth—“the deeps.” In the end, the ocean was let in to claim the dark sooty tunnels sloping an astonishing five kilometres beneath the Atlantic. But there were some things even the salt water couldn’t wash away.

It was 1999, and I was working on a cover story for the Halifax weekly, The Coast, about miners who had been exposed to radiation. The research would lead me to Rosalie Bertell, who had become known internationally for her expertise in the dangers of ionizing radiation, having worked for a decade as a senior a cancer researcher at Roswell Park Cancer Institute in Buffalo, New York, specializing in its health effects.

Rosalie Bertell giving her acceptance speech at the Right Livelihood Awards ceremony in 1986.

Standing out by the locked gates with a view of the shuttered buildings was Forbes Harding, the mine’s cable belt electrician. We met to talk about how he was exposed to dangerous gamma radiation while working at the mine’s breaker chute between 1993 and 1999. The source was an unlabelled nuclear gauge used to keep the coal belt moving. One day, when it stopped working, Harding and a co-worker, Danny Dean, unwittingly handled live radiation. When I met Harding, he was experiencing a “crushing and burning” pain in his left hand and worrying lumps had developed on his vocal cords and thyroid.

All in all, nearly 50 mine workers, including electricians, mechanics and welders, were exposed to the dangerous gamma rays, and not one of them knew it.

Officials at the crown corporation that owned the mine—the Cape Breton Development Corporation (Devco)—had never warned the men of the dangers they faced, even though the risks were entirely avoidable. The federal agency responsible for licensing and safety of nuclear devices, then named the Atomic Energy Control Board, overlooked the faulty gauge—there were two—used to keep the coal moving swiftly through each chute.

The way it worked was each gauge contained a chunk of cesium 137, a radioactive isotope about the size of a pinky finger, which sent an invisible beam of radiation through the chute to the opposite side, where a radiation detector was mounted. If there was a coal pile up, it would block the full strength of the beam from reaching the detector, stopping the coal belt. Coal pile ups happened every shift, Harding explained, and when it did it was his job to climb a ladder and lean from the waist up through a small hatch and clear the pile up, which usually took about 40 minutes each time. No one ever told him that before he leaned into the chutes he was supposed to close the gauge’s lead shutter, effectively shutting off the radiation beam.

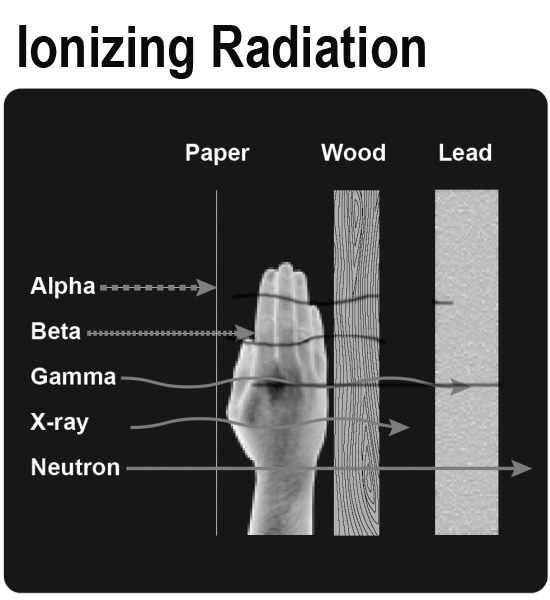

Supervisors told everyone the gauges were “as safe as a wrist watch” or “smoke detector.” No one told them gamma rays were powerful enough to penetrate concrete.

In 1996, when Danny Dean unwittingly handled one of the gauges, the chunk of cesium—the radioactive component—dropped right into his hand. He held it for nearly a half hour. A couple years later, when he was only 38 years old, he started peeing blood clots, and was diagnosed with bladder cancer—extremely rare for a non-smoker his age. After two surgeries his cancer went into remission, but he had to undergo scopes four times a year.

Eventually Devco was given a slap on the wrist for the negligence. It was ultimately the workers who paid the real price. 1 2

Coal miner, Phalen Mine, Nova Scotia Archives

Every single day each of us is exposed to a certain amount of radiation—watching television, wearing luminous dial watches, smoking cigarettes—all sources of exposure measured in milliseiverts (mSv). A smoke detector emits about 0.0001 mSv a year. A 10,000 km airplane flight delivers 0.05 mSv, while a medical x-ray delivers 0.4 mSv.

For comparison purposes, the cesium in the locking mechanism at the Phalen mine emitted 1,300 mSv an hour from its tip.

When it comes to what’s considered acceptable radiation exposure, Canada is legally bound to follow the guidelines put out by the International Commission on Radiological Protection, and it has determined that the yearly allowable limit for safe radiation exposure is one mSv, which is based on a morally tenuous standard called the ALARA principle: “as low as reasonably achievable, taking into account economic and social factors.”

This is where Bertell enters this story. Nearly 20 years earlier, in 1983, along with renowned physicist and peace activist Ursula Franklin, as well as Dermot McLoughlin, a medical radiologist, Bertell founded the International Institute of Concern for Public Health (IICPH) and set up an office in Toronto. The focus of the organization was environmental hazards—not just nuclear ones—and it would publish a journal International Perspectives in Public Health, with Bertell as the editor-in-chief.

As previously mentioned in Part 1 of this series, Bertell had done extensive research on the subject of radiation, including for her 1985 book on the subject. As mentioned, she also spent nearly a decade (1969-1978) working at the Roswell Park Memorial Institute in Buffalo, where she looked at the harm caused by what she argued was the unnecessary use of diagnostic x-rays—a subject we’ll return to later in this series.

I reached out to Bertell by email for the Phalen mine piece, told her about the miners and asked her what she thought about the dose level the ICRP deemed “safe.” She said these so-called acceptable levels are actually “unacceptable,” and that they were 50 times higher than what is truly “safe,” where “safe is defined to mean it would cause no more than one cancer death per million exposed per year.”

Bertell went on to point out that the risk estimates used by the nuclear establishment were too low by a factor of four, essentially underestimating the number of potential fatalities. In her estimation, the maximum permissible exposure to a million people would not result in one fatality, as the standards maintain, but would cause 200 fatal cancers.

“This [“safe”] exposure will also cause non-fatal cancers, promote cancers which it did not cause, initiate auto-immune diseases, genetic damage, teratogenic damage, and various other difficulties,” she explained.

Cover of the 250th issue of The Coast, May 2000. Photo: Linda Pannozzo; The cover story was an excerpt from Frederick Street: Life and Death on Canada’s Love Canal, a book written by Elizabeth May and Maude Barlow.

It was later, when I was helping Elizabeth May with some research for her book, Frederick Street: Life and Death on Canada’s Love Canal, that I had the honour of meeting Bertell. May hired her to do a peer review of a highly questionable government-funded study about the health effects of the toxic legacy of steel-making in Sydney, Nova Scotia. She was a tiny woman, but when I met her, it was plain to see that she was actually a giant.

“Her ethics and values and history were quite extraordinary and unlike anybody else I knew. She was a powerful figure, a force to be reckoned with,” May says in a telephone interview for this piece.

May is a lawyer, environmental activist, and author of numerous books. She has been the Member of Parliament for Saanich–Gulf Islands in British Columbia since 2011, many of those years also serving as the leader of the Green Party. She was also the executive director of the Sierra Club of Canada from 1986 to 2006, and prior to that she did a two-year stint working as a senior policy advisor to Thomas McMillan, then environment minister in the Brian Mulroney government. She resigned on principle when McMillan granted permits for a dam project without performing a proper environmental assessment.

It was during those years at the Sierra Club that May met Bertell, when they were both working on nuclear/ radiation issues. When she needed someone to go over the commissioned study from consulting firm CanTox Environmental (now called Intrinsik), she knew it had to be Bertell.

“I brought her in on the Sydney Tar Ponds because we were having so much trouble, as you recall, getting any level of government to act. At that point, [Bertell] had set up a consulting firm [IICPH] and we contracted with them out of Sierra Club of Canada. I was trying to find different ways to agitate, to get the Sydney Tar Ponds really cleaned up and not buried,” May explains.

The steel plant was first owned and operated by Dominion Iron and Steel Company, but later, in 1966, under threat of closure, the provincial government expropriated the mill and took over operations, while the feds expropriated the coal mines and the coke ovens. For nearly a century, coal was baked in ovens to make “coke” for the steel plant, and the resulting legacy was a toxic one.

The “Sydney tar ponds,” as they became known, was essentially a 34-hectare tidal estuary linking Muggah Creek to Sydney Harbour, except it had been transformed into 700,000 metric tonnes of noxious sludge and slag. The coke ovens site contained an additional 560,000 tonnes of contaminated soil.3

The study Bertell was tasked to review involved a small brook that separates the cluster of 17 house on Frederick St. from the coke ovens site. In 1998 the brook started to ooze yellow “goo” from its banks and toxicity tests by Health Canada showed high levels, all above the guidelines, of arsenic, lead, benzene, copper, and PAHs—chemicals known to caused cancers, birth defects, heart disease, kidney disease, brain damage, and immune deficiencies.

Shortly after the ooze was discovered, the NS Department of Health paid CanTox Environmental to assess the health risk associated with living on Frederick St. The question the consulting firm was asked to answer was: do the chemicals “have the potential to cause health problems in people now or in the future?” Blood and hair samples from the residents were collected and also used in the study.

It took CanTox only 3 weeks to write its report, in which it concluded the chemicals posed “no immediate health risk”—something the province’s Chief Medical Officer of Health had concluded previously on repeated occasions. CanTox also stated “chemical exposures estimated or measured in the Frederick St. area are not elevated enough to cause measurable adverse health effects.”

Based on these findings, the government decided moving the residents was unnecessary.

According to Bertell and Roger Dixon, an industrial hygienist who co-authored the review, the CanTox study was based on “meagre sampling” and contained far too many assumptions and unknowns to draw any definitive conclusions.

At the release of the review, to a packed audience filled with residents of Frederick St., Bertell called for the creation of a 3-5 km buffer zone around the remediation of the site: “If anything is touched or disturbed the people should be removed,” she said. They should also be registered as having been near a toxic site to track future health effects. Bertell and Dixon also noted that the CanTox health risk assessment was generated by a computer model, which was the wrong kind of study to ask for.

“It’s like eating soup with a fork. They should have been doing health surveillance,” argued Dixon.

According to Bertell, CanTox was assessing risk for the purposes of liability not health. Sydney Steel Corporation (SYSCO) was after all a provincial crown corporation and any admission of pollution being linked to health problems could also mean an admission of liability.

Graphic depicting the forms of radiation and how far they are able to penetrate, US Nuclear Regulatory Commission

In 1985 Bertell received an honorary degree from Mount Saint Vincent University in Halifax.

In her acceptance speech she said:

“I would suggest that wherever you are living after graduation, you find for yourselves a community of questionners who are willing to challenge and be challenged on these issues.” Some of the issues she was referring to were “stockpiling of nuclear weapons,” the “slow poisoning of drinking water, air and food with toxic waste,” and “using workers as expendables for hazardous occupations.”

“You will need such a community if you are to consistently choose to move away from past societal behaviour which is now proving to be so destructive to society and life itself.”

Critiquing this destructive behaviour and taking on big industrial interests on behalf of the vulnerable, whether it be nuclear or otherwise, was what Bertell dedicated her life to. Throughout she was often preoccupied by one searing question, one that often got to the crux of things: who decided what the “permissible” levels were, whether it was radiation doses, or guidelines for toxic substances in air, water, or soil?

Bertell knew full well that “acceptable” levels of risk were often balanced by the benefits of a technology and that “permissible” did not mean “safe.” She “became prominent among those who argued that determining the acceptability of such risk-benefit ratios was a social or political choice, not a scientific one,” writes her biographer, Mary-Louise Engels.

If there is such a thing as a ‘nuclear narrative’—and let’s not pretend there isn’t—it is that low-dose radiation, whether it comes from bomb testing, reactors, or x-rays, poses no significant risk to human health. According to Engels, it was this “contention” that she spent “the most productive part of her career in combatting.”

Bertell was attuned to the fact that conflicts of interest were part and parcel of the standard-setting processes, and along with these came the official narratives to support them.

For instance, “The [International Commission on Radiological Protection] ICRP members have been predominantly associated with the military and with medical radiological societies, all of which had a vested interest in promoting the use of radiation and downplaying its risks,” writes Engels.

Opposing what she saw as an unethical system is what eventually led to Bertell losing her own mooring in the field of cancer research.

Rosalie Bertell receives an honorary degree from Mount Saint Vincent University in Halifax, 1985.

[Stay tuned for Part 3, which will look at the period in which Bertell realized working within the system would mean she’d have to stay quiet, so she did neither.]

On June 1, 2000, the Atomic Energy Control Act of 1946 was revamped to include stiffer fines and penalties for companies that don’t take seriously the rules around using nuclear devices. Under this new law, the negligence Devco visited upon its workers would have been punishable by fines of up to $3.5 million. But when Devco pleaded guilty in 2000 to seven charges of regulatory negligence, it did so under the old Act. The charges against Devco amounted to a litany of failures: failure to ensure that only trained personnel informed of the hazards of the gauge used it or worked around it. Failure to provide a survey metre to measure radiation. Failure to ensure that the device was dismantled by someone trained to do so. Failure to maintain a list of names of all the people who used and handled the device or any radioactive substances. Failure to maintain records confirming the shutter on the gauge was closed when workers were in the coal chute, to which it was attached. And finally, failure to limit the dose of ionizing radiation. Devco was fined the maximum $25,000 – and Judge David Ryan said at the time, “It just boggles the mind… in some areas of the mine more attention would have been given to a loose light bulb.” The men who suffered were referred to as “victims of neglect.”

This section was adapted from my February 2001 piece written for The Coast. A version of this article also appeared in The Ottawa Citizen. In 2002, the article won first place in the “Resources Category,” of the Better Newspapers Competition of the Atlantic Community Newspapers Association.

The coke ovens were closed in 1988, but it took 25 years and $400 million dollars from the province and the feds to finally “clean up” the site. In the end, incineration was ruled out and the sludge was essentially buried -- “stabilized and solidified” with the use of poured cement. According to a news report at the time, the area was “covered with a plastic sheet, layered with soil and planted with grass. Some local residents have expressed disquiet, saying they expected a cleanup, not a coverup. The local authority though has approved the plan, calling it the "least risky" option.”

I'm really enjoying this series, Linda. I remember and admire Rosalie Bertell and her work very well from our Natural Life Magazine publishing days. She was definitely a force!

Thank you again Linda.