In the opening pages of the 1985 book Amusing Ourselves To Death: Public Discourse in the Age of Show Business, Neil Postman expresses relief that the year 1984 had come and gone and that “America” had not been visited by the “nightmares” predicted in George Orwell’s book that “we will be overcome by an externally imposed oppression.”

“The roots of liberal democracy had held,” Postman wrote.

When Postman penned his book, he believed that while Americans had escaped Big Brother— the external oppression predicted by Orwell—he could not say the same for another “dark vision” presented in a “slightly older, slightly less well known, equally chilling” book by Aldous Huxley in Brave New World.

Postman wrote:

In Huxley’s vision, no Big Brother is required to deprive people of their autonomy, maturity and history. As he saw it, people will come to love their oppression, to adore the technologies that undo their capacities to think… What Orwell feared were those who would ban books. What Huxley feared was that there would be no reason to ban a book, for there would be no one who wanted to read one. Orwell feared those who would deprive us of information. Huxley feared those who would give us so much that we would be reduced to passivity and egoism. Orwell feared the truth would be concealed from us. Huxley feared the truth would be drowned in a sea of irrelevance.

Forty years ago, Postman thought Huxley, and not Orwell, was right. He thought Huxley’s vision was “well under way toward being realized,” and that “in the age of advance technology, spiritual devastation is more likely to come from an enemy with a smiling face than from one whose countenance exudes suspicion and hate. In the Huxleyan prophecy, Big Brother does not watch us, by his choice. We watch him, by ours. There is no need for wardens or gates or Ministries of Truth.”

For Postman, it was the “Age of Television” that was ushering in the Huxleyan future. Postman likened the new “mode of public conversation” to an ideology because for Postman, technology was ideology “equipped with a program for social change”—that “imposes a way of life, a set of relations among people and ideas, about which there has been no consensus, no discussion and no opposition. Only compliance.”

Postman thought Orwell’s dystopia would not likely happen because “everything in our background has prepared us to know and resist a prison when the gates begin to close around us.” But “who is prepared to take arms against a sea of amusements?”

In 1985 Postman was relieved to find that liberal democracy was still intact.

Nearly forty years later, not so much.

If Postman were alive today, I think he’d be alarmed by the machinery of thought-control that has made its way into so-called democracies. Orwell warned about this machinery in Nineteen Eighty-Four and in 1985 Postman noted in his book that it had been operating in “scores of countries and on millions of people” by that point, but not in the United States.

Well, it has now arrived, everywhere pretty much.

Postman also said—and I think this is key—that Orwell was correct in insisting that it “makes little difference if our wardens are inspired by right- or left-wing ideologies. The gates of the prison are equally impenetrable, surveillance equally rigorous, icon-worship equally pervasive.”

Groupthink and authoritarian measures including censorship and surveillance—subject matter that I’ve explored in The Quaking Swamp Journal—have been embraced by a large swath of the “left” in the name of stopping the identical outcome on the “right.” The end result will of course be the same—an erosion of a free and open society characterized by fear and polarization, and the inability to have unimpeded discourse which is necessary in a functioning democracy.

For me, the most disturbing thing to witness over the last number of years has been the erosion of hard-won principles: freedom of expression, speech, and assembly, bodily autonomy, and informed consent. Disturbing because these were hard-won by progressives—many of the same people who have now abandoned these principles in the name of safety and security. It’s a short-sighted and dangerous justification to be making.

Again, as Postman so wisely stated, it makes no difference who the wardens are, we will still be surrounded by prison gates.

Postman noted that we would not be able to shut down what he called “the technological apparatus” that is ushering in these dystopian futures, but that there “must be a solution.”

Postman was writing in the 1980s about television, which he said “serves us most ill when it co-opts serious modes of discourse – news, politics, science, education, commerce, religion – and turns them into entertainment packages.” 1

“To maintain that technology is neutral, to make the assumption that technology is always a friend to culture is, at this late hour, stupidity plain and simple.” Postman says that when you introduce new technologies—new modes of transportation, new alphabets, a printing press with moveable type, speed-of-light transmission of images, ”you make a cultural revolution. Without a vote. Without polemics. Without guerrilla resistance.” All you need to make the new ideologies ushered in is a populace that “devoutly believes in the inevitability of progress.”

Now—in the Age of Information—we have computers and cell phones, which, despite their benefits, have also ushered in a myriad of harms.

The problem does not reside in what people watch. The problem is that we watch. The solution must be found in how we watch… There has been no worthwhile discussion, let alone widespread public understanding, of what information is and how it gives direction to a culture…no medium is excessively dangerous if its users understand what its dangers are.

Postman said that asking the important questions about the quality of the information we are receiving and the role of information in society is enough to start “breaking the spell,” and that we need to learn to distance ourselves from “forms of information.”

In the end, Postman said Huxley’s solution was that we needed to understand that “what afflicted the people in Brave New World was not that they were laughing instead of thinking, but that they did not know what they were laughing about and why they had stopped thinking.”

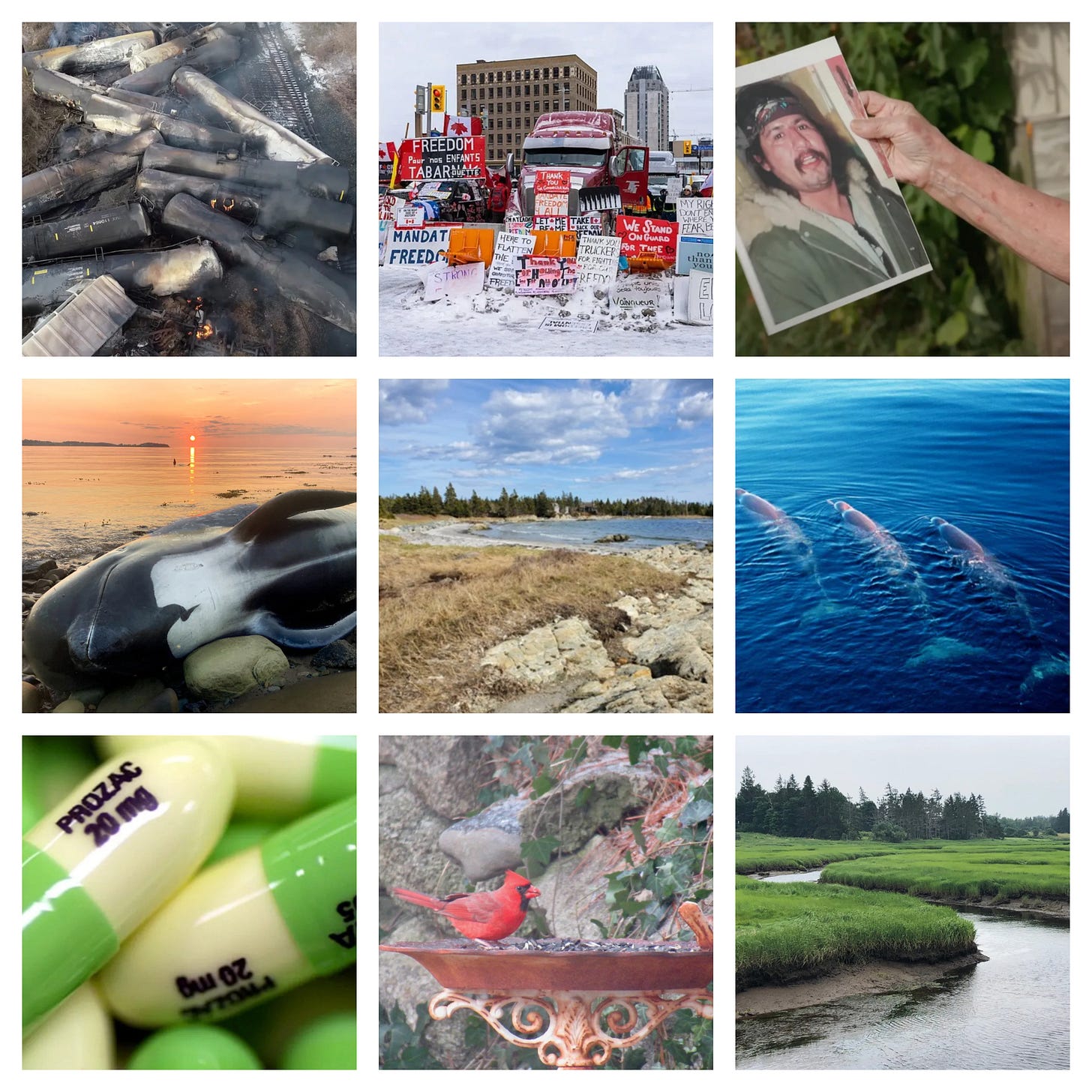

Selection of cover photos from stories published in 2023

When I started this newsletter on January 10, 2022, part of my goal was to break free from the dictates of groupthink and the official narratives—which are created to benefit the powerful—and explore what was not being reported, or not being reported properly in the press. I also wanted to try to resist what I saw as a collective descent into fear, hate, and polarization by presenting some nuance to stories that had become highly divisive. I also wanted to embrace a line from Mitchell Stephens’ book The History of News, where he writes: “We can hope that journalists will wander more frequently beyond the boundaries of news itself and occasionally adopt less hurried, more searching perspectives. And there is always the hope that… the news will enlarge a mind.” I hope that I’ve achieved at least some of these things.

So, on the second anniversary of this newsletter, I want to tell you that I’m very worried about where things are going — in journalism and in society — and I’ve tried to shine a light on this darkness. It’s all I can do really.

I also want to take the opportunity to express my gratitude for all of you: for taking an interest in my writing, commenting (publicly or privately), sharing, or taking out a paid subscription. I am especially grateful to those of you who have sent me messages of support. These mean more to me than you’ll ever know.

All the ways that you participate, help reinforce my commitment to this project.

A salt marsh near Baie Verte, New Brunswick. Photo: Linda Pannozzo

Some stats:

In case you’re interested, I’ve written 73 stories in the last two years and the top three most read stories are:

A Sledgehammer to Crack a Peanut

Flattening the Curve May Shorten Your Life

Pushing Back the Hospital Curtain

The top three most read stories in 2023:

Remote Control (Part 1, Part 2, Part 3)

In Secrecy We Trust (Part 1, Part 2)

“Safety is our top priority,” unless you’re a logging company, then the profit motive is

Stay tuned for an upcoming piece on wetlands of special significance and how the Nova Scotia government has downgraded their protection while continuing to misinform the public about doing so. I’ve said it before, and I’ll say it again, what the government calls transparent is about as diaphanous as a rubber tire.

Only here, at the Quaking Swamp Journal.

Sometime before 2000, just a few years before his death, Postman gave a talk about the five things we need to know about technological change:

Culture always pays a price for new technology.

The advantages and disadvantages of a new technology are never evenly distributed in a population — there are harms and benefits and we need to always ask who are the winners and who are the losers?

“The medium is the message,” (Marshall McLuhan) and every technology “has a philosophy which is given expression in how the technology makes people use their minds,” says Postman.

Technological change doesn’t just add something to a society, it changes it entirely — “the consequences of technological change are always vast, often unpredictable and largely irreversible.”

Beware of technology becoming a “form of idolatry” — instead it should be viewed as a “strange intruder” and it’s “capacity for good or evil rests entirely on human awareness of what it does for us and to us.”

Happy Anniversary! While I don't always agree with you, I'm always grateful for you and your mind.

I wonder how much our perception of a more democratic 'past', and the steady decline of a societal state of honour, openness and generosity is heavily coloured by where each of stands in relation to privilege. I would imagine that not many Indigenous people look back and consider the foundation of this current society as a just one, but rather catastrophic.

I grew up as one member of the last instalment of baby-boomers. My family was working class, white, and protestant. We were proud of our United Empire Loyalist heritage. My ancestors had occupied land in the Niagara area for several generations by the time I came along. While we were not rich we always had food on the table, and for me the symbol of our working class ethic was my father's lunch pail. But I was informed by a friend once that not everyone had that Leave-it-to-Beaver-kinda household to grow up in.

So I wonder if the current state of technological perversity we find ourselves in is not really a departure from the past but actually some sort of logical unfolding on the same continuum.

Thanks for raising the questions and initiating the conversation Linda.